The term “MiG” has become virtually synonymous with “Russian fighter.” Indeed, when U.S. Navy F-14s downed two Libyan Su-22s, many commentators unintentionally rubbed salt into OKB Sukhoi’s wounds by referring to the Fitters as “MiGs.” This is an indication of how successful OKB MiG has been in designing the most widely used jet fighters in the world, the more recent models of which are still world-class in equipment and performance.

Cuba’s air force, the Defensa Antiaérea y Fuerza Aérea Revolucionaria or DAAFAR (Anti-aircraft Defense and Revolutionary Air Force) for its initials in Spanish, has operated MiG aircraft for almost forty years now, unfortunately behind a screen of secrecy that makes an assessment of their service difficult. Through open sources we don’t even have an accurate inventory of the different types which Cuba has employed over the years. What follows is an attempt to pull together the best information, reconcile the conflicts, and present as accurate a picture as possible of the career of MiG aircraft in the DAAFAR.

MiG-15

The DAAFAR operated MiG-15bis, MiG-15Rbis, and MiG-15UTIs. Known serials for the fighter version include 18, 26 (?), 50 and 53, and for the trainer variant 02, 26 (?) and 89.

The first MiG-15s – 20 MiG-15s and 4 MiG-15UTIs – arrived in Cuba at the end of May, 1961 (one month after the Bay of Pigs Operation) and assembly commenced at the San Antonio de los Baños Airbase on June 6, with Soviet assistance. The first Cuban to fly a MiG-15 was Enrique Carreras on 24 June, 1961.

Six jet-qualified Cuban pilots – veterans of the Bay of Pigs – were selected for training in the new MiGs. These were Enrique Carreras, Álvaro Prendes, Rafael del Pino, Gustavo Bourzac, Alberto Fernández and Douglas Rudd. They commenced an urgent technical course (under Russian tutelage) in Cuba during July 1961, moved on to practical training in August, and started squadron operations in November. The first squadron Commander was Enrique Carreras with Álvaro Prendes as deputy. Flight commanders were Alberto Fernández, Rafael del Pino and Douglas Rudd.

More Cubans attended flight training in Czechoslovakia and China, some after a few hours in Piper PA-22 Tri-Pacers, left over from the defunct Fuerza Aérea del Ejército de Cuba -FAEC (Cuban Army Air Force.) Two more MiG-15bis squadrons were organized during 1962 as the “checos” (Czech-trained pilots) and the “chinos” (Chinese-trained pilots) returned to Cuba, the former in March and the latter somewhat later.

Meanwhile, in June-December 1961, fifty Russian MiG-15 and MiG-19 pilots were in Cuba to fly the forty-one MiG-15bis, MiG-15UTI and MiG-19P aircraft provided by the USSR. By June 1962, Cuban pilots were considered capable enough in the MiG-15bis to participate in an anti-invasion exercise. By the time of the Missile Crisis of October 1962 there were 36 MiG-15bis and MiG-15Rbis in Cuba, dispersed to several bases: San Antonio, Santa Clara, Camagüey and Holguín. They frequently tried to intercept U.S. RF-101 and RF-8 reconnaissance aircraft over Cuba. Future Cuban cosmonaut Arnaldo Tamayo flew 20 interception and reconnaissance sorties during the time of the crisis.

The MiG-15UTI trainers enjoyed a long, successful career in DAAFAR service, thirty or so eventually being acquired. As in other air forces, they were replaced by Czech Aero L-39Cs, which first supplemented and later supplanted them in the advanced training role from 1982 onwards.

MiG-17

Versions operated by the DAAFAR include the MiG-17AS “Fresco A” (most, if not all, of these built in Czechoslovakia) and the MiG-17F “Fresco C.” The first fighter-bomber MiG-17ASs arrived in Cuba in 1964, destination Santa Clara Airbase, where MiG-17s replaced MiG-15s little by little. This workhorse was operationally employed primarily as a fighter- bomber. Known serials include 101, 215, 216, 230, 232 and 237.

On 5 October 1969 Lieutenant Eduardo Guerra Jiménez landed MiG-17AS serial “FAR-232” at Homestead AFB, Florida. The aircraft was returned to Cuba, but before it left, some of its interesting features were captured in both official and unofficial photos of the event. Of particular note, K-13 “Atoll” missile rails – characteristic of the AS – were mounted under its outer wings. It was painted light gray overall instead of natural metal (except the drop tanks, which were bare metal except for a red nose cap), and its fuselage insignia was just a star in an inverted triangle without the blue disk.

According to one source, the DAAFAR team which recovered the aircraft came in on a transport which had been hastily modified with reconnaissance equipment. As might be expected, this impromptu spy-plane suffered “navigational errors” and overflew several sensitive U.S. installations – the Turkey Point nuclear power station being mentioned specifically – during the course of its mission.

Guerra Jiménez was one of the squadron commanders in the Santa Clara regiment. Because of his defection a great purge was made of the DAAFAR leadership, during which pilot friends of Guerra and even those simply thought to be acquainted with foreigners suffered expulsion from the FAR.

In December of 1975 Castro sent a squadron with 9 MiG-17Fs and one MiG-15UTI to the FAPLA (armed forces of the MPLA – “Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola“) air force. The commander of the MiG-17 squadron was Major José A. Montes. Shortly after their arrival, these MiG-17Fs commenced operations against the FLEC (Cabinda Enclave Liberation Front) separatist movement.

Their zone of operations was in Cabinda and the north of Angola, while MiG-21MFs worked south and east. These operations led to victory in April, 1976. In the years following the Cuban MiG-17s operated against UNITA (National Union for the Total Independence of Angola) until replaced by newer MiG-21s, when they were passed to the Angolans.

Another part of Africa in which Cuban MiG-17s saw action was Ethiopia. In December, 1977, one squadron of MiG-17s and one squadron of MiG-21s were employed in operations against Somalian forces invading the Ogaden (desert region of Ethiopia adjoining Somalia, the boundary of which was never acknowledged by the latter country) which resulted in the Somalians being pushed completely out of that area by March 13. One MiG-17 pilot was killed when his aircraft was shot down by Somalian AAA. It is interesting to note that in this conflict, Cuban MiG-17s and MiG-21s flew combat missions alongside Ethiopian F-5A/B/Es against Somalian MiG-17s and MiG-21s! Despite rumors to the contrary, during the 70s and 80s, Cuban pilots did not participate in the Eritrean conflict. In September, 1989, due to the changing world situation, the last Cubans left Ethiopia, leaving behind their equipment.

In 1973 Cuban MiG-17 pilots were employed in South Yemen, along the borders with North Yemen and Saudi Arabia. Also during the 70s a group of Cuban pilots flew MiG-17s in Guinea. They helped form and train the local air force and participated in missions against violations of Guinean airspace and territorial waters.

Cuba received a total of 100 or so of these aircraft and they lasted in service until around 1981, being replaced entirely by MiG-21s and MiG-23s.

MiG-19

The MiG-19 “Farmer” was operated in small numbers by the Cubans and had a short operational career. The MiG-19P “Farmer B” night/all-weather interceptor was the only version in service and, of these, all were Russian-built (no Chinese). The only known serial is 88.

The MiG-19P was Cuba’s first radar-equipped fighter, eight of which arrived in November 1961. These were assembled the following month at San Antonio de los Baños Airbase, with the first flight by a Cuban pilot being undertaken by – who else – Enrique Carreras. A total of 12 was received, these being formed into one squadron with Cuban pilots (some of them Czech-trained) and Russian instructors. Eleven were in service at San Antonio de los Baños during the October 1962 Missile Crisis. The MiG-19Ps served until 1966 when they were replaced by all-weather MiG-21s.

Apparently, much like the East Germans, who considered the MiG-19 a “widowmaker” as half of theirs – 10 out of 24 – were lost in accidents, Cuban pilots were not happy with the MiG-19. They considered it unstable, complex, “problematic” and, given the choice, they much preferred the MiG-17 or MiG-21. In fact, when MiG-21PFMs became available, the DAAFAR dumped the MiG-19Ps right away.

MiG-21

Numerically the MiG-21 has been the most important warplane in the DAAFAR for most of its existence. Models received included the MiG-21F-13 “Fishbed C“, MiG-21PF “Fishbed D“, MiG-21PFM “Fishbed F“, MiG-21PFMA, MiG-21R “Fishbed N“, MiG-21MF “Fishbed J,” MiG-21bis “Fishbed L“, MiG-21U “Mongol A” and MiG-21UM “Mongol B.” Known serials include 10, 11, 39 and 43 (F-13); 362, 367, 368, 371, 374, 377, 379, 384 (PFM); 500, 501 (UM); 514, 518, 520 (PFMA); 600, 602, 622, 632, 656, 660, 663 (MF); 772 and 780 (Bis).

The first Soviet unit to operate the MiG-21F-13 was the 32nd Guards Fighter Regiment stationed at Kubinka Airfield near Moscow, which received its first jets in 1961. In June 1962, the unit received secret orders to travel by train to the port of Baltiisk and embark for Cuba. It deployed with forty MiG-F-13s, six MiG-15UTIs and one Yak-12 liaison aircraft. On arrival in Cuba it was renumbered the 231st Fighter Regiment and placed under the Soviet 12th Anti-Aircraft Defense Division. Its MiG-21s were frantically assembled at Santa Clara and, on September 18, the first flight of a MiG-21 in Cuba was made. After combat alarms on October 22nd, the regiment dispersed between the airbases of San Antonio de los Baños, Santa Clara, and Camagüey. The closest thing to actual combat the unit saw, however, occurred on November 4 when a Russian-flown MiG-21 intercepted two USAF F-104Cs from the 479th Tactical Fighter Wing on a reconnaissance sortie near Santa Clara, but the F-104s disengaged and retired northward.

Although inconclusive, this engagement was not without consequences. All of these MiG-21F-13s carried the red stars of the Soviet Air Force, the VVS. Cubans and Russians monitoring the US radio noticed that the US pilots reported being intercepted by “MiGs with red stars.” Hence, from then on all of the MiG-21s were painted in Cuban colors immediately.

During the Cuban Missile Crisis the USAF discovered, much to its dismay, that the APS-95 (upgraded APS-20) surveillance radars of its Lockheed EC-121 airborne early warning and control (AEW & C, precursor to AWACS) aircraft couldn’t detect low-flying MiGs because of ground clutter. As an emergency measure the QRC-248 system was developed to interrogate the MiGs’ SRO-2 “Odd Rods” IFF (transponder). This device proved quite successful in monitoring Cuban low-altitude MiG activity and was later employed in Vietnam.

After the Cuban Missile Crisis, in early 1963, the Soviet high command decided to pass these advanced warplanes on to Cuba and to train local pilots and technicians to operate and maintain them. In April, Cuban pilots first soloed, and the first Cuban MiG-21F-13 regiment was officially established on August 10.

On 18 May 1970 several MiG-21s overflew the Bahamas to send a pointed message to the Bahamian government, which was holding fourteen Cuban fisherman it claimed had been fishing in its waters. The fishermen were released.

Seven years later, on September 10, 1977, one squadron of MiG-21MFs, under the command of Rafael del Pino, overflew Puerto Plata in the Dominican Republic to press for the release of the merchant ship Capitán Leo, which, enroute to Angola, had violated Dominican waters and had been interned by the authorities. The plan was to bomb Puerto Plata and Santiago de los Caballeros the next day if the Dominican government didn’t release the ship, but after hurried negotiations it did. This impressive overflight received the name of “Operation PICO.”

During the war in Ethiopia in 1978 one squadron of MiG-21bis and several MiG-21Rs, in hundreds of flights, destroyed numerous Somalian tanks and artillery pieces. Several MiG-21s were lost and one pilot was killed by AAA (anti-aircraft artillery) fire.

On May 10, 1980, two DAAFAR MiG-21s attacked the Bahamian patrol vessel HMBS Flamingo, which had arrested four Cuban fishing vessels. Cuba admitted this to be in error and paid indemnity.

A continuing problem was the pursuit of light aircraft that violated Cuban airspace. On February 21st, 1982 a MiG-21PFMA was lost over water and its pilot killed when he lost control while maneuvering at slow speed while in pursuit of one of those light planes.

Although not quite combat, MiG-21s were employed in numerous exercises with Soviet forces, such as intercepting Tupolev Tu-95 “Bear” reconnaissance aircraft as they flew to and from Cuba, and “attacking” the Soviet fleet when it was operating in the Caribbean.

The Cuban MiG-21s have also been used to provide cover for such functions as the 26th of July festivities and Congresses of the Communist Party, and served as escorts for Fidel Castro’s trips outside Cuba.

To supplement Cuba’s regular aviation units in Angola, in December 1975, Castro ordered MiG-21MFs to be shipped directly from the USSR. In January 1976, giant Antonov An-22 transports airlifted one squadron (twelve MiG-21MFs) to that African country from the Soviet Union.

On February 4, 1976, UNITA forces detected and surrounded a Cuban/Angolan reconnaissance patrol led by Lieutenant Artemio Cruza. The patrol had been operating well behind enemy lines, beyond, in fact, the normal range of a MiG-21. Rafael del Pino requested permission to mount a rescue operation and was flabbergasted when it was refused on the grounds that if the patrol had been doing their job properly, they should never have been discovered in the first place! On his own initiative del Pino planned and mounted the rescue for which he alone, in a MiG-21 fitted with three external tanks, flew top cover. The next day, with him as a sort of solo RESCAP keeping the UNITA troops’ heads down, Mi-8 helicopters were able to extract the team and fly them to safety. Del Pino was lucky to escape punishment for this act of intrepidity, being given a “second chance” because of his previously unblemished service record. However, as a consequence of his actions, on May 2, 1976, the then Minister of Defense, Raúl Castro, did relieve del Pino of his post as commander of the MiG-21 squadron in Angola, replacing him with Benigno Cortés.

One of the few combats of the war involving enemy aircraft happened on March 13, 1976 when, while attacking the UNITA aerodrome at Gago Coutinho, a flight of four MiG-21MFs surprised a Fokker F-27 on the ground, unloading arms. Rafael Del Pino dispatched it with an S-24 unguided rocket. In general, air-to-air engagements were very rare during the war in Angola, most action consisting of “mud moving” and most combat casualties being due to groundfire, AAA, and SAMs. “Rare” does not mean it never happened, however.

On November 6, 1981, then-Major Johan Rankin of the South African Air Force (SAAF) shot down a MiG-21MF (the SAAF identified it as a “MiG-21bis“), flown by Major Leonel Ponce, over Angola with 30mm gunfire while flying a Mirage F-1CZ. It was the SAAF’s first victory in air-to-air combat since Korea. Almost a year later, on October 5, 1982, he officially repeated the feat, also with gunfire (after he had damaged the MiG’s wingman with a Matra 550 missile). It must be noted that although he was credited with this victory, according to Cuban sources both MiGs involved in this latter action (flown by Lieutenants Raciel Marrero Rodríguez and Gilberto Ortiz Pérez) recovered safely to their base at Lubango, although with some battle damage.

The only recorded aerial victory for the Cuban MiG-21s occurred on April 3, 1986, when a pair of MiG-21MFs intercepted two C-130s reportedly carrying cargo for UNITA. They shot down one while the other escaped seriously damaged. According to South Africa (and the International Air Transport Association) they actually shot down a civilian C-130 registered to the Angolan government airline.

The best-documented loss of a Cuban-flown MiG-21 over Angola was on October 28, 1987, when an armed two-seater MiG-21UM was downed by ground fire near Luvuei. The two crewmembers successfully ejected and were captured by UNITA.

MiG-23

The DAAFAR received forty-five of the MiG-23BN “Flogger H” and two MiG-23UB “Flogger Cs” in September 1978. Known serials include 710 and 722 for the BNs and 701 for a UB.

The MiG-23s were stationed at San Antonio de los Baños. Acquisition of these aircraft did more than just improve the strike capability of the DAAFAR, it also had far-reaching effects in the U.S. political arena. Some U.S. Congressmen questioned whether their presence in the island violated the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis agreement with Russia, since they were clearly more effective than the Il-28 “Beagle” bombers which had been so objectionable fifteen years before. Assurances that this model wasn’t equipped to carry nuclear weapons weren’t entirely accepted, and continued critical examination of Soviet/Cuban forces led to the “discovery” of the “Soviet Brigade” on the island. Seen as part of a larger pattern of appeasement, this was a contributing factor in President Carter’s defeat in the next election.

During the US invasion of Grenada in 1983 the MiG-23BNs were armed in preparation to strike targets in Florida, such as Homestead AFB and the Turkey Point nuclear reactor, in the event the Grenada operation turned out to be the precursor to a combined U.S. / Caribbean invasion of Cuba.

In 1984 the Soviet Union supplied fifteen or so MiG-23MF “Flogger B” interceptors. These were the only air-to-air MiG-23s in the Cuban inventory until the MLs came home from Angola. Reports of the DAAFAR operating the MiG-23MS “Flogger E” appear to be unsubstantiated.

On March 20, 1991, Major Orestes Lorenzo Pérez landed MiG-23BN “FAR-722” at NAS Key West, Florida. As in earlier cases, the airplane was returned. Lorenzo himself, though, embarked on a quest to get his family out of Cuba. Frustrated in every conventional approach to the problem, on December 19, 1992, he flew a rented Cessna 310 to Cuba, picked up his wife and kids, and brought them back to the United States. This story is documented in his book “Wings of the Morning“, which also provides an intriguing glimpse into the DAAFAR operations, including combat in Angola where he flew more than 40 sorties in MiG-21s.

In the mid-’80s Cuba obtained fifty MiG-23MLs which were sent directly to Angola, where they were employed primarily in the ground attack role until late in the war. During late 1987 to middle 1988 – the time of the Cuito Cuanavale battles – they began to be used also as interceptors against the South African Air Force.

Angola’s premier fighter-bomber was the Su-22 “Fitter“, and there are persistent rumors that these, also, were flown by Cuban pilots. They would have been the only Fitter-qualified Cuban pilots in the DAAFAR, since Cuba has never operated the type. The best evidence, though, is that the Su-22s were flown exclusively by Angolans (who crashed an awful lot of them!)

According to Cuban sources their MiG-23MLs downed five South African combat aircraft over Angola:

- A MiG-23 shot down one Mirage F-1AZ during the first part of 1987 in the north of Namibia. South Africa admits to losing a Mirage F-1AZ but claimed it was hit by an IR SAM, probably an SA-7 or SA-9.

- On September 27, 1987, Cuban Major Alberto Ley Rivas and Lieutenant Chao Gondin in MiG-23MLs engaged two Mirage F-1CZs of the Sout African Air Force’s 3rd Squadron and fired three R-60 (“AA-8 Aphid” IR-homing) missiles. According to them, one F-1CZ exploded upon impact by an R-60 and crashed in enemy territory, and the other retired to Namibia after being struck by a second missile. This aircraft lost its drag chute and sustained serious damage to its hydraulics. When the pilot, Captain Arthur Piercy, landed at his base at Rundu, Namibia, he ran off the end of the runway, over a ditch, and struck a rock which scraped off the landing gear and caused the ejection seat to fire. Unfortunately the parachute did not deploy before Captain Piercy hit the ground and his back was broken. He survived but was medically retired from the SAAF. The aircraft was cannibalized for parts to keep #205 flying. Major Rivas was awarded 1.5 victories for this action, and Lt. Gondin a half kill. This event is well-known in Cuba and confirmed by the Russians and Angolans, but not by the South Africans. According to them, the pilot of the second Mirage, Commander Carlo Gagiano, fired a Matra 550 IR missile at the MiGs (without result) and, after the action, escorted Piercy to Rundu where he (at least) landed safely.

- Also on September 27, 1987, a MiG-23ML shot down a South African Puma helicopter with an R-60 missile.

- One Impala jet was claimed destroyed by a MiG-23, no date given.

In other combats, on September 10, 1987, South African Mirage F-1CZs intercepted ten MiG-23MLs (a mixed force of eight bombers and two escorts). The bombers broke off the attack and the Mirages engaged the escorts with Matra 550 missiles. On gun camera film one missile can be seen exploding close behind a MiG-23, but the Mirage pilot did not claim a victory. On February 25, 1988, Eladio Avila engaged two Mirage F-1s while flying a MiG-23ML. Both sides fired missiles but there was no result. Lastly, in another inconclusive engagement, Captain Orlando Carbo in a MiG-23ML reported being attacked by three Mirage F-1s which fired three V-3 Kukri IR missiles but missed.

The MiG-23 fleet did sustain losses, most of them due to the Stinger shoulder-fired SAMs supplied to the insurgents by the US. UNITA downed a MiG-23ML and a MiG-23UB in 1985, the latter on December 9, 1985. Also, in the book “General Del Pino Speaks” Rafael Del Pino comments on how three MiG-23s were lost in one week during combat in Angola. When Cuban forces withdrew, surviving MiG-23MLs were shipped to Cuba. In fact, the MiG-23ML on exhibition at the DAAFAR museum in Havana is a veteran of Angola.

Some Cuban sources credit the MiG-23 with winning the war in Angola and forcing South Africa to democratize. According to this version, the final touch to the war happened in June 1988. After their defeat at Cuito Cuanavale the South Africans retired to Namibia. The MiG-23 totally conquered the air and the Mirage F-1 of the SAAF, routed and impotent to reconquer the air without disastrous losses, abandoned the war and left the air to the MiG-23 to pound their army with impunity.

But on June 7, 1988, Castro indicated to the Cuban command in Angola that according to intelligence information the SAAF was planning a surprise attack, and ordered that MiG-23s be prepared to bomb South African bases in Namibia and other objectives in case of such a strike, and serve as a warning to South Africa. On June 26, South African troops counterattacked near Chipa. The next day, twelve Cuban MiG-23MLs with demolition bombs appeared over the hydroelectric dam at Ruacana- Calueque (in Namibia), which was protected by the South African Army and provided electricity to most of Namibia. The attack was a total success (13 deaths admitted by the South African forces), the South Africans abandoned the complex, and when Cuban troops arrived several days later, they found all the signs of a disaster: Armored vehicles overturned and burned out, blood and bloodsoaked pieces of uniforms, and the turbines completely destroyed.

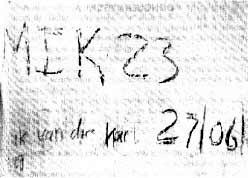

Cuba advertised its ability to continue its advance into Namibia, but it was too much for South Africa which on 27 June signaled hastily to US mediator Chester Crocker and requested a ceasefire and negotiations, which ended with a peace treaty under which South Africa abandoned Angola and Namibia, stopped supporting UNITA, and began to democratize. Cubans encountered a wall written on in Afrikaans by the South Africans with an elegant phrase: “MIK23 sak van die kart.” They translated it as “The MiG-23 broke our heart.”

Back in Cuba, another well-known employment of a MiG-23 in a “combat” role was the shootdown of two Hermanos al Rescate Cessna Skymasters on February 24, 1996. A grainy still from video, shot at the time from the lone surviving Cessna, doesn’t reveal many details, but does show the unmistakable outline of a MiG-23. One MiG-23UB was teamed with two MiG-29UBs to perform the interception.

MiG-29

The Cuban MiG-29 force may have been originally planned to be 35 – 45 fighter jets (enough for a full regiment), but economic problems reduced the buy to only twelve MiG-29 “Fulcrum As” and two two-seat MiG-29UB “Fulcrum Bs“. These arrived in October 1989 and, after assembly, were test-flown on April 19, 1990. The serials appear to run in the 900 range.

The following anecdote shows that problems were not just economic, but political as well: After Castro saw the MiG-29s duing one of his trips, he asked the Soviet Union for some, but Mikhail Gorbachev (trying to warm up political relations with the United States) did not respond. After months of silence, the Russians through their ambassador Kapto, told Castro that he couldn’t get any because they weren’t making them any more.

Castro was unhappy with the Russians’ response, but at least it was a reply of some kind. The following day, Ambassador Kapto met with a General of the DAAFAR. The General asked Kapto if he had seen the TV transmissions from America about MiGs in production and how they were being exported and were visiting other countries. Kapto understood what Fidel was insinuating and transmitted this to Moscow. Because of this, the Russian began sending MiG-29s, but Cuba never received the total planned amount because the Soviet Union disintegrated before it could be done.

The roles of the MiG-23 and MiG-29 in the Hermanos shootdown seem somewhat obscure. Why launch aircraft of different types for such a mission? However, the rationale for this peculiar turn of events makes perfect sense. The loss of MiG fighters attempting to maneuver with slower planes (like the MiG-21PFM in 1982, described above) showed that a slow and maneuverable aircraft like a Cessna 337 is a very difficult target for a fast jet fighter like the MiG-21 or MiG-23. On the other hand, the MiG-29 (like the Su-27) is very maneuverable and can “yank and bank” very well at slower speeds. Because the DAAFAR planned to use MiG-29UBs to attack the Cessna 337s, selected FAR pilots trained for the mission by practicing incterceptions of a Cuban civil plane, the Polish-built PZL-104 Wilga.

The MiG-23UB stayed high and served served as a radio relay between ground radar controllers and the MiG29UBs to help vector them to the Hermanos al Rescate Cessnas. Lt. Col. Lorenzo Alberto Pérez Pérez (in conjunction with other crew members) was the pilot of the MiG-29UB that shot down the two Cessna 337s, using R-60M missiles. The use of two MiGs (with 4 pilots on board, all having a plenty of flight time from missions flown in Africa) was to help control the delicate operation and shows how meticulously planned the operation was. More so the Cuban government was well informed of each flight of the Hermanos airplanes by their Red Avispa spy ring, especially Juan Pablo Roque.

Epilogue

As Dan Hagedorn points out in his excellent book “Central American and Caribbean Air Forces“, Cuba’s peculiar position in the Cold War lent it an importance all out of proportion to its size. One aspect of this disproportion was the DAAFAR’s large fleet of MiG fighters. In some ways the history of this fleet mirrors the course of Cuban/Soviet relations: Virtual integration, followed by collapse. Will improvements in the Cuban economy and in relations with the new Russian regime revive the DAAFAR? It will be interesting to see, especially in light of the following:

“April 26: MOSCOW, CUBA DISCUSS MILITARY COOPERATION. Deputy Minister of the Cuban Revolutionary Armed Forces Julio Casas arrived in Moscow for talks with the Russian military’s “troika”: Defense Minister Sergey Ivanov, Chief of Staff Anatoly Kvashnin and Deputy Defense Minister (and Chairman of the influential International Military-Technical Cooperation Committee) Mikhail Dmitriyev. Casas’ talks focused on the joint program to modernize the Cuban Air Defense System and Air Force established during President Putin’s visit to Havana last December, the Military News Agency reports. Under the agreement, Russia has promised to provide training for Cuban military personnel and to repair Cuba’s fleet of Soviet-made MiG-21 Fishbed, MiG-23 Flogger and MiG-29 Fulcrum aircraft.”

This article was a truly LAAHS team effort. Thanks to (In alphabetical order) Jorge Cantera, Dan Hagedorn, Gary Kuhn, Mario Overall and Tulio Soto for all their critiques, additional information, and suggested sources.

Update: Excellent aero-historians Hélio Higuchi and Paulo Roberto Bastos have published what promises to be the definitive account on the Cuban MiGs. You can get your copy at Amazon by clicking here or by clicking on the book cover below:

Also, you can purchase it directly from Harpia Publishing here.

A superb overview. As I understand MiG-21 single seater 672 was seen being prepared for flight along with a MiG-21UM during Bastion 2016. 1120 and 1121 of the UM variant were reportedly seen active in Nov. 2016 along with 634 and 672 of the bis variant with 614 being seenctive in 2014. Of the MiG-23s, 2 UBs were seen in 2016 along with at least one ML – three aircraft were seen in 2014. Of the MiG-29s, it is suggested that the type was wfu in 2017. There should be around four MiG-21bis/UM and at least six MiG-23ML/UB in service at present.

Wow! Didn’t know that Cubans retired their MiG-29s around the time that news reports surfaced regarding mysterious illnesses affecting American and Canadian diplomats in Havana. What is the basis for info regarding the retirement of the MiG-29s from Cuban service? Also note that the Scramble website lists the Cuban MiG-23s as retired (https://www.scramble.nl/planning/orbats/cuba/cuba-air-air-defence-force). So it seems that the Cubans may have left only the MiG-21 in service due to the high operating cost of the MiG-23 and MiG-29.

Cuba never had 12 MiG-29, Only 5 MiG-29A and two MiG-29UB, total 7 MiG-29.

Yo vivi toda esa epoca en la DAAFAR, DE LOS MIG 15 MIG21UTI Y MIG 23 ENTRE LAS BASES DE SAN ANTONIO Y HOLGUIN TUBE

ENTRENAMIENTO PARA PILOTO DE LOS MIG 21 DESPUES DE SERVIR COMO ESPECIALISTA DE SISTEMA HIDRAULICOS DE LOS MIG SERVI EN LA DAAFAR”

Excellent article on the Migs and FAR. My neighbor Tony was in the first group of Cuban pilots trained in Czechoslovakia to fly Mig-15s. His family was divided by politics with him and mother staying in Cuba and father and sister becoming exiles. Tony was first generation Cuban parents were Spanish. I visited Cuba twice in 201, on the first trip I visited my childhood home and stood outside Tony’s house. Some of the anti communist kids from the neighborhood burned down Tony’s 59 Chrysler Imperial.

The Cuban Revolutionary Air Force chose to use MiG-29s and MiG-23s in the Brothers to the Rescue shootdown because they mistook the Cessna Skymasters flown by Brothers to the Rescue for the military version of the Super Skymaster, the O-2 Bird Dog, thereby claiming that the BTTR was seeking to provoke the Cuban people into overthrowing the communist government and making the Cuban nation part of the US again (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1996_shootdown_of_Brothers_to_the_Rescue_aircraft).

Sorry I cant respond in Spanish, my humble apologies.

Successful MiG’s, RUSM. Look guys, “a MiG at six is better than no MiG at all”, circa, 1972, skies over NVN. I personally know MiGs and Russian Culture, vodka and Russian Pilots, so let there be no mistake about MiG’s v free world fighters. One of these days, hope to be re-united in the skies. Tks, Dax Cario.

The “Mik23 sak van die kart” story is nonsense. Translated into Afrikaans it actually means “Aim 23 fall off the wagon.” No SADF person would write that gibberish. A MiG-23 and its pilot was lost to AAA in this raid. The Flogger was not the key to a political solution in Angola/Namibia. It was more complex than that. South Africa was on the verge of deploying the Cheetah fighter armed with the V3S (Israeli Python), which was more than a match for the MiG-23, while it worked on the Super Mirage F1 and Carver. Both sides really just lost interest in an expensive war that made no sense as the USSR began to go into decline. So many people died on both sides fighting a failed Soviet proxy war. I honor those who fought on both sides.

Propaganda that can’t be backed with facts. Typical Cuban behavior.

I can’t believe that nobody fact checks this idiot. It is very easy to do. People just believe the gibberish that this guy wrote.

“Mik23 sak van die kart” I can also confirm that this is nonsensical. Translated it says “Aim 23, bag of the wagon”. This is a big LOL moment.

Hello. The last picture in this article, shows 2 mig-27. As far as I know, there are no mig-27 in DAAFAR. I would like an explanation

Those are MiG-23BN Flogger H jets, of which the DAAFAR had no less than 24. Hope this answers your question.

Cuban -Soviet Mig there were many in the Cuban Air Force I worked there.

They hundreds of Migs in Cuba.

Cuban -Soviet Mig there were many in the Cuban Air Force I worked there…