A little over ninety years ago, an impressive single-engined biplane, painted ivory white and decorated with brilliant red cheat lines and lettering, was flying at an altitude of about 1,500 meters over the waters of the Atlantic Ocean. She had taken off fifteen minutes to five in the morning, from the Sevillean Airport of Tablada, Spain, loaded with more than five thousand liters of fuel, and after a long and difficult take off run down a runway that had been purposefully lengthened for the occasion.

The biplane has by now flown for fifteen hours, pretending to reach the Island of Cuba. This is the first time that an attempt was being made to cross the Atlantic through its central portion, the widest and most difficult. The pilot, squeezed in a narrow and uncomfortable cockpit, is 27 years old member of the Aviación Militar Española (Spanish Military Aviation), in which he holds the rank of Lieutenant; he was born in the City of Figueres, Catalonia. His name: Joaquín Collar Serra. Behind him, in just a little larger but equally uncomfortable cockpit, sits the navigator and commander of the expedition and the father of the idea original idea. He is also a Spanish military aviator and his rank is that of a Captain. The 38 years old officer was born in the Spanish Guadalajara, in Castilla La Nueva, although through his mother, he is of Catalonian descent; his name is Mariano Barberán y Tros de Llarduya and was considered in his time, as an expert in aerial navigation techniques.

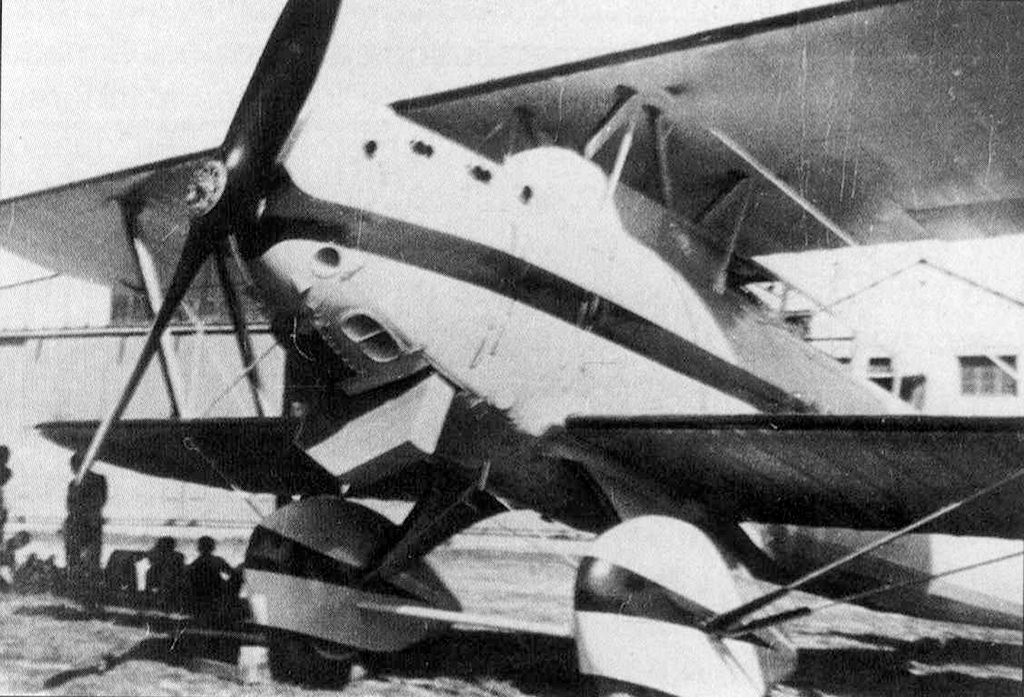

The aviators are on board a superb flying machine conceived in France by the engineers of the Breguet Company, but built in Getafe, near Madrid, by Construcciones Aeronáuticas S.A. On the sides of the fuselage she sports with pride her name: “Cuatro Vientos.” It is June 10th, 1933.

At this moment, Joaquín Collar is not piloting the airplane. A bothersome gastritis, causing stomach pains and cramping has caused the pilot to develop a high fever, forcing him to relinquish for a few hours, the controls to his companion Berberán. Joaquín Collar will try to overcome his indisposition, caused no doubt, by the uncomfortable position in the cabin for so many hours, and also by the nervous and the terrible stress under which he has been for the last weeks. Berberán has to multiply his efforts. While Joaquín Collar is trying to rest, he is piloting the airplane and keeping an eye on the fuel consumption, which dangles over their heads like an axe since their take off in Sevilla, the previous morning. Additionally, he had also to continually perform the necessary calculations to find their position, to ascertain if they had deviated from their intended route, and to effect the necessary heading corrections.

Joaquín Collar meanwhile, thinks and tries to organize his feelings. Remembers when as a child (the son of a military family – his father Luis Collar, a Cavalry Lieutenant) was destined from an early age to follow on the military tradition, so in 1921 when he was barely 15 years old, entered the Cavalry Academy from where he would graduate as a Lieutenant in 1926, when he was twenty years old.

He would remember how, seduced by the new technologies, had requested to be admitted as a student, first to the airplane observer courses and later to the pilot course, a title he obtained in 1929 with the number one of his class. He remembered how his ability and precision as a pilot had him assigned to the “Escuadrilla de Experimentación en Vuelo,” (Flight Testing Squadron) based in the Cuatro Vientos aerodrome in Madrid, same place where the observers school was located, and of which his now flight companion, Mariano Berberán, was the Director.

Joaquín Collar also remembers how his young spirit had felt repulsed by the scandalous level of political corruption in Spain, following the Dictatorship of Primo de Rivera and how, because of it, he had been involved in the attempted Republican coup d’etat of 1930, together with some prestigious pilot colleagues, such as Ramón Franco, Ángel Pastor, Hidalgo de Cisneros, La Roquette, Alvarez Buylla, Roa, Martínez de Aragón and others, and how after the failed attempt, he had to escape into exile first to Portugal and then to France, where he would remain while in Spain, him and his co-conspirators were tried in-absentia and expelled from the Army.

He Remembers, and when he does that, he cannot avoid smiling despite the terrible pain he feels, that his exile had been brief since, by April of the following year, simple municipal elections had caused the fall of the monarchy and the proclamation of the Republic, and this had allowed him to return from France and rejoin the Flight Testing Squadron, but now decorated with the aura of a Republican hero.

He remembered too, when nine months previously, in October of 1932, the Director General de Aeronáutica (Director General of Aeronautics) had called him to propose to be part of Berberán’s team. Joaquín Collar was a pilot noted for his ability and technical capabilities, and Berberán himself had suggested him for the position. Besides, Joaquín Collar was also known for his proven republicanism. Who else other than him, better to become a representative to the whole world, of the progresses made by the New Spain born in 1931?

Joaquín Collar had smiled. The proposal thrilled him as a pilot, independently of the supposed political connotations. He knew Berberán well enough to know that the proposal was not just an illusion, nor a daredevil adventure. Berberán was synonymous of prevision, exactness, and calculation. If Berberán had gotten a project in motion, it was because the feat was possible and had great possibilities of success. Berberán was not the kind of man to leave anything to chance.

Collar was now feeling better, as if the trip down memory lane had allowed him to free himself of the frenetic stress of the previous weeks. If he kept going like this, he would be soon in condition to take on the controls once again.

Really, Joaquín Collar thought, the last weeks had been extraordinarily exciting. Since at Getafe, during the first two weeks in April, they had started visiting the factory in which the “Cuatro Vientos” was slowly being built. They witnessed how the airplane had evolved, starting from a giant metallic cylinder, into an enormous fuel deposit which had been initially dubbed “El Bidon” (Spanish for the fuel tank). Breguet had built “Bidones” in France and these had been employed to set new records for distance and endurance. In Getafe, the French company had built two of these for the Spanish Military Aviation, serial numbers 71 and 72, in which Isidoro Jiménez and Francisco Iglesias had covered themselves with glory in 1928, flying between Spain and Irak, in an attempt to establish a new straight line distance world record; and in 1929 when they flew from Sevilla to Buenos Aires, and from there to Chile and up along the Pacific Coast of South America, until reaching Guatemala, ending their trip in La Havana, all this accomplished on board of airplane number 72, which had been christened with the name of “Jesús del Gran Poder.” And with the airplane number 71, Capitán Cipriano Rodríguez and Teniente Carlos Haya had also covered themselves in glory, beating three world speed records for a closed circuit for 2,000 and 5,000 kilometers and also by completing a non-stop flight between Sevilla and Equatorial Guinea.

But the “Cuatro Vientos” was not just a “Bidón” but a “Super Bidón”, a bigger size version with more fuel capacity, which the French engineers had designed to attempt -and achieve- the non-stop jump between Europe and North America flying East to West. In 1927, Lindbergh pioneered the flight route connecting North America and Europe for the first time. However, it wasn’t until 1931 that Dieudonné Costes and Maurice Bellonte accomplished the West-to-East flight aboard the “Point d’Interrogation,” an aircraft that was an enhanced version of the “Cuatro Vientos.”

Collar brought to mind his discussions – and those of Mariano Barberán – with the technicians at Construcciones Aeronáuticas: Engineers Luís Sousa Peco, Aguilera and others, regarding how the pilots’ cockpits should be equipped, where each of the flight instruments should be placed, the accessibility of the control valves for the different fuel tanks, where to place the compasses in order to diminish as much as possible the already reduced visibility. He also recalled Berberan’s demands: The navigator’s seat should be foldable, otherwise, how could he stand up to use the sextant when the time came to shoot the sun and stars and thus be able to calculate the airplane’s position? They also needed to have a small table available where to deploy their navigational charts, and to effect their calculations, and all of this should be combined with the duality of controls of the airplane. It was a real challenge for the technicians.

But it had been finally achieved and on 15 April 1933, himself together with Joaquín Collar Serra and Barberán had attended in Getafe, the engineers and the technicians responsible for the airplane and the engine, and the High Command of the Spanish Military Aviation, to the introduction in society, of the “Cuatro Vientos”. The astonishing white airplane, with its elegant red stripes on the fuselage and wing leading edges, stabilizers and vertical stabilizer leading edge, and the titles spelling the name ” Cuatro Vientos” gracing the sides of the fuselage and with the brilliant Republican tri-color cockades on the wings and rudder, had been rolled out of the assembly buildings of Construcciones Aeronauticas, S.A., and had been presented to the authorities and the press. Almost immediately, the flight-testing began, the calculations for fuel consumption, load-carrying capabilities, take off run distances under different load and atmospheric conditions. The behavior of the airplane and engine during long distance flights had been carefully studied.

Eventually, on April 15, 1933, Barberán, along with Joaquín Collar Serra, attended an event in Getafe. This gathering included engineers, technicians responsible for the airplane and its engine, and the High Command of the Spanish Military Aviation. The purpose of the event was to formally introduce the “Cuatro Vientos” to the public. The remarkable white aircraft, adorned with elegant featured the name “Cuatro Vientos” prominently displayed on the fuselage. Republican tri-color cockades added a brilliant touch to the wings and rudder. Subsequently, extensive flight testing commenced, involving calculations for fuel consumption, load-carrying capabilities, and take-off run distances under diverse load and atmospheric conditions. The performance of the airplane and engine during long-distance flights underwent thorough scrutiny and analysis.

On a couple of occasions, the daring aviators had flown to Cape Juby, Las Palmas and back, in a flight lasting more than fifteen hours. And both, the airplane and its powerful Hispano Suiza engine of 650 Hp, had functioned perfectly, like the precision machinery that both were. Collar also recalled how, just a few days before, when the training and testing flights had been concluded and when all they were waiting for, to begin their flight was a favorable meteorological forecast, they had been received by the President of the Government, the Manuel Azaña he admired so much and who had wished them the best of luck in the adventure they were about to start… Just a week had gone by since the interview with Azaña and it already seemed like forever, as if it had happened years ago. And he reminisced how, on the third day of June they had concluded the test flights and the airplane had gone back to the factory, where the engine had been replaced and the airplane had been prepared for the beginning of their Trans-Atlantic journey.

To Collar’s mind also comes Modesto Madariaga, the Sergeant-Mechanic from Toledo who, with his great deal of expertise had helped them to prepare the airplane and who should be already waiting for them in Havana, where he had traveled by ship, three weeks earlier. Madariaga was one of the mechanics with the most experience in the Spanish Military Aviation; he had joined the Army and had completed the aviation mechanic courses. A few years had passed since he finished his studies. Llorente had taken him as a crew member in one of the three hydroplanes that, constituting the “Patrulla Atlántida” had linked for the first time Spain and the Equatorial Guinea in December of 1926.

Ramón Franco, the legendary hydroplane pilot, had also taken Madariaga with him together with Julio Ruiz de Alda and Eduardo González Gallarza, during their failed attempt to fly around the world in 1928, flying the Dornier Wal No. 16, the first to be built in Spain by Construcciones Aeronáuticas. (Collar could not suppress a smile when he remembered how Franco had cheated, replacing the aircraft by No. 15, which had been built in Italy, and made him feel more confident.) But the hydroplane, not mattering that had been built in Italy, broke down during the first stage of the flight, and after floating several days near the Azores Islands, was rescued together with the crew, by a British aircraft carrier, who took them to Gibraltar when all the world thought them lost forever. That hard experience notwithstanding, Madariaga had shown enthusiasm when he was asked to become part of the team.

Madariaga had struggled with the engine and the airplane, he had suggested modifications to the Construcciones Aeronáuticas technicians, as well as to Hispano Suiza, the company that was responsible for the engine. And the technicians had listened to his opinions. The mechanic skills were evident all around the Cuatro Vientos, Collar could hear the engine’s sound perfectly, smooth as silk, and the airplane responded immediately and softly, to the command inputs.

Almost five hours have gone by since he began to feel indisposed, and now he is feeling much better. His stomach is not hurting anymore, and the feverish sensation has disappeared. Very likely, everything has been caused by nervous tension. He tells Barberán about it. He is ready to take over the controls again, and this will allow Barberán to rest and relax for a while, so he can immediately concentrate in the navigation calculations.

Collar is now piloting the “Cuatro Vientos.” Mariano Barberán, his body cramped due to the forced position he had to maintain while piloting the airplane, can now change position and stand up, and slide backwards the canopy’s roof, and shoot some readings with the sextant, which will allow him to plot their location. They have been flying now for twenty hours, and it is forty five minutes past midnight, June 11, 1933, Spanish time, which translates to three hours earlier, local time that is, fifteen minutes to ten at night, and he will have to shoot two different stars in order to calculate their latitude. Darkness does not allow him to estimate drift. He has not been able to do it for quite some time now. When there was light, the overcast has forced them to fly above the clouds, higher than 1,2000 meters altitude, and this made impossible for him to make a drift estimate. Anyways, he thinks, the flight has been smooth and they have not encountered any side winds, so the drift must have been minuscule, if at all. The heading has always been 256º since they left Seville, and the latitudes he has been able to calculate earlier, had confirmed the existence of a minimal drift (only + 3º shortly before they had to fly over the clouds). Since then, and having made the necessary heading corrections, the wind had practically stopped blowing.

This memory makes him consider how, during the flight preparations, his partner Cubillo, from the Flight Protection Services, had completed a meteorological forecast that had been turning out to be amazingly precise. “After flying 200 miles, upon leaving Seville, you will find low clouds and you’ll have to fly on top of them.” Cubillo’s forecast had been accurately true, to the point where when they were over the Archipelago of Madeira, one of their checkpoints, they had been able to see only the summits of some peaks, poking out of the sea of clouds over which they were flying. Cubillo had also forecasted that after some ten hours of flight time, they would encounter again, another cloud bank… And it had happened exactly like that. Cubillo had also said that from that point on, they could come across dense storm formations, that they would do well to avoid. They had seen those when they had been flying for thirteen hours, almost at the same moment when, through a break in the clouds, they had been able to see a ship down below, the only variation in the otherwise monotonous cruise. After this, Joaquín Collar had become indisposed and he had been too busy to think about anything else but piloting the airplane and even, at the same time, attempting to shoot some readings on the moon’s elevation with the sextant to calculate their latitude, and he had managed to do so, but without being too confident with the results obtained. Now, with Joaquín Collar recovered and flying the airplane he could shoot the elevations with more ease, and calculate the position more accurately. Once the stars elevations had been obtained, Barberán immerses in the consultation of the tables and the necessary calculations. Minutes later, he feels more at ease… He has verified the latitude, and they are on their planned track. Now, they can relax for a few hours. He pours himself some coffee from one of the thermos they are carrying and eats a bite. While he does this and the same as Joaquín Collar had done before, Mariano Barberán organizes his memories…

In reality, his life and Collar’s had many parallels, especially when it came to the first years of their lives. His father, an Officer in the Engineers Corps, had fallen in love with his mother, and married her later on, while he had been stationed in Lleida. Both of them were then, of Catalonian descent, although Barberán had been born in Guadalajara, where his father had been stationed at the time of his birth, eleven years earlier than that of his crew companion. Likewise, as in the case of Joaquín Collar, the fact that he had been born to a military family, had somehow defined his future and him too, when reaching fifteen years of age, had entered the Army’s Engineers Academy, where he had graduated in 1915 with the rank of “Teniente” (Lieutenant). With a passion for mathematics, he had a solid scientific foundation and excellent teaching qualities. Had not he been a military man, he could have been a Professor in any University or Superior School for Engineers. His passion for science had made him passionate about the new technologies of his time: Aviation and telecommunications. In 1919 he had completed the Course for Airplane Observer, and as such, had risen to the rank of Capitán (Captain) in 1920, and had been stationed in Morocco, where he had been wounded during aerial operations against the rebel tribes in El Rif, and for this action he had been awarded the Medalla Militar (Military Medal). In 1923, he had been sent to Paris for eight months, to receive specialization courses in radiotelegraphy, electronics and radio navigation. Berberán also remembers how, when he had returned to Spain, he had decided to complete his training and took the Course for Airplane Pilot, obtaining the title, despite his shortsightedness, in April of 1924.

Barberán also remembered when Ramón Franco had told him about his trans-Atlantic flight project, using a hydroplane and how, Franco and himself had prepared the initial documents for the project and had sent it to the High Command with the purpose of obtaining the necessary authorizations. And how, once the adventure had been authorized, he had worked very hard in the scientific and technical aspects of the navigation of that Dornier hydroplane that would be baptized with the meaningful name of “Plus Ultra.”

He could not suppress a bitter smile when he remembered how, in the end, he had not been included as part of the crew of the “Plus Ultra” and how Julio Ruíz de Alda had replaced him. Franco had begged Braberán to reconsider his position, as he needed him as part of the crew. Even when they made a stop at Las Palmas, and before they began their flight to the Cape Verde Islands and Fernando de Noronha near Brazil, and taking advantage of Barberán’s being in Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Franco had insisted up to the last moment… But Barberán had refused to become a member of the hydro’s crew. And it was not because he did not want to. It was a matter of principle… Mariano Barberán, Captain of Engineers, had expelled himself from the “Servicio de Aviación Militar” when he had requested his discharge in 1925. Curiously, this was another thing he had in common with his flying companion: Collar had been “expelled” in 1930, because of his participation in an attempted Republican coup, but had returned later, with all the honors. Mariano Berberán himself, had requested his discharge from the service, passing to a “C” situation – available – in the Corps of Engineers, for a matter of principles… How did that happen?

He remembered it so perfectly well. In 1925, he had been named “Jefe de la Segunda Escuadrilla” (Commander of the Second Squadron) formed by two Light bombing squadrons flying the Breguet XIX, destined to reinforce the African Air Forces, always so short in material and manpower due to the daily missions they had to accomplish in that theater of operations. The commander for the other squadron was his buddy Alejandro Arias Salgado, while the group was under the command of Commander Felipe Díaz Sandino… The whole group had left Getafe, stopping to refuel in Granada, before making the jump over water to Melilla. He remembered that Granada had really bad weather and the group ended up stuck at the La Armilla airdrome, while the meteorological situation improved… Meanwhile, crew members went to Granada, since the Corpus Holidays were in effect. And all this happened while Mariano Berberán insisted, time and again, that they should resume their flight because they were needed in Africa. Comandante Díaz Sandino did not want to risk his group in an over water flight with such a dismal weather and kept delaying the departure orders, and this in turn, caused an increasing of the already growing tensions between Díaz Sandino and Arias Salgado on one side, and Berberán on the other, until the latter took a decision of grave consequences. Without waiting for orders from his superior, he took off with his squadron, towards Melilla, reaching the place without incident. When the next day, the rest of the group arrived, the situation exploded. There was a severe altercation between Arias Salgado and Barberán while at the same time, Díaz Sandino harshly reconvened him, accusing him of the grave fault of insubordination. Berberán thought then, and continued to think now, that he had done the right thing, because when he felt that the higher command did not support him, he made the decision to request his discharge from the Servicio de Aeronáutica, passing immediately to “situation C” (available) and was sent to Las Palmas de Gran Canaria –which back then, was the equivalent of an exile- while awaiting a definitive destination within the Army Corps of Engineers. And all of this had coincided with the last details and preparations for the flight of the “Plus Ultra.” His wishes to take part in one of the grand raid flights had vanished, at least for the time being.

Mariano Barberán though, was an extremely valuable man and the Servicio de Aeronáutica Militar had at last, demanded his re-incorporation and assigned him first, as a professor and then as the Director (Principal) of the Military Aviation’s School for Navigators and Observers, located between the bases of Cuatro Vientos and Los Alcázares. His reputation, always growing, as an expert scientific in aerial navigation, had seen him to become an advisor to all the attempts for long-range flights. He had advised the flight of the “Patrulla Elcano” between Madrid and Manila; to Llorente’s with the “Patrulla Atlántida” between Melilla and the Equatorial Guinea; the attempt at breaking the record, by Jiménez and Iglesias flying the Breguet Number 72 between Madrid and Nasriya (Irak); to the new flight of those aviators, with their the “Jesús del Gran Poder” through the majority of the countries in South and Central America; to the two failed attempts by Ramón Franco, the first with the Wal Number 16 and then, with the Super-Wal “Numancia” and in all of them, he had limited himself to the role of an advisor and technical advisor.

He could recall how, just as he had re-joined the Military Aviation Service in 1926, had prepared together with González-Gil a non-stop flight between Spain and the Equatorial Guinea flying the prototype for the reconnaissance airplane Loring R-III, and how the High Command had not authorized the flight, arguing that the airplane, being a prototype, had not been sufficiently tested. He remembered how, by the end of 1928, had hoped that the Military Aviation would let him use the Breguet number 71, another “Bidon” similar to the “Jesús del Gran Poder” to attempt with it, a flight between Madrid and New York, and becoming thus the first to fly the North Atlantic flying on a Westerly direction. Unfortunately for him, the airplane had been entrusted to Rodriguez and Haya, with whom he had flown from Madrid to Villa Cisneros, in one of the preparation flights for the Great Raid of those hard working pilots, to the Equatorial Guinea. He had also advised Tauler and Haya on their flight around the Iberian Peninsula, but he had not participated in that one, either. He had never been the protagonist on any of the great flights, although he had participated in one way or another in the preparations for all of them, and already in 1932, he was 37 years old, which meant that he was beginning to be a little bit too old for an adventure of such magnitude. Besides, Berberán thought he was not an adventurer, but a scientist and what he was doing now onboard the “Cuatro Vientos” was no adventure. He, Mariano Berberan believed deeply in the future of aviation as a means of air transportation for mail, passengers and merchandise, but for that to become possible, routes should be opened and people should learn to navigate them. And this was exactly what he was attempting to do onboard the “Cuatro Vientos”: To open a new route. The South Atlantic had been already tamed, since the Portuguese Gago Coutinho and Sacadura Cabral had crossed it for the first time. For bad or worse, in 1923, several crossings had already been made and since 1930, the French with the Aeropostale and the Germans with Lufthansa had begun to experiment with a route between Western Africa and Brazil, and the beginning of regular flights had been just announced that same year. The North Atlantic had also been conquered, both ways, since 1930. It was clear that it had to be crossed following two different routes, depending on the time of the year: Either across the Northern route via Newfoundland, Iceland and Ireland, or the Southern route, via the Bermuda Islands, the Azores and Portugal. The North-Americans were getting ready to get those lines going, pretty soon… There were left only the trans-Pacific routes, which were outside the zone of interest for Spain, and finally, the Central Atlantic zone, the aerial linkage between Europe and Mesoamérica, with the added difficulty factor that it was the area where the ocean was at its widest.

Barberán interrupts his reminiscing for a while… They have been flying for 24 hours and 30 minutes and now, bright and unmistakable, over the horizon, the Polar Star shines. This is a perfect opportunity to shoot the elevation of the star with the sextant and from this data, calculate their position. He passes a written note to Joaquín Collar: “Will shoot Polar Star’s height… Maintain stable flight.” Collar knew exactly what was expected of him under these circumstances… He should not allow the airplane the minimal oscillation in any of its three axis. The airplane should remain rock steady during the few minutes necessary so Berberán could align the mirrors in the sextant with the horizon line and with the star whose elevation he wanted to measure. Barberán measures the angle that indicates the star’s height and then complete the necessary calculations: His latitude is 24º North, just where they were supposed to be. The minimal drift they had experience, had even decreased. They were for all practical purposes, over their theoretical route.

Mariano Barberán cannot avoid a deep sigh of relief, and at the same time, of satisfaction. How precisely had he calculated their route!!! And also thinks: What a magnificent pilot Joaquín Collar is!!! Cold and smart, despite his young age… Not prone to be carried away by enthusiasm… Following with an unbelievable precision, the flight instructions… And on the other hand, although he has a reputation -probably well deserved- of being a merry young man, a womanizer, he is humble and professionally modest, knowing and assuming that his role is that of simply executing the ideas and orders from Mariano Barberán. No, he had not made a mistake when he proposed him to the High Command, as the pilot for the “Cuatro Vientos.”

Little by little, Mariano Barberán goes back to his previous thoughts, to his reflecting, to organize his memories… Yes, he was thirty-eight years old and had few opportunities to be the protagonist of a great flight. That’s why he had thought about the project for the flight to Havana and Mexico. In reality, Mexico was not the last Hispano-American country left to visit by the Spanish Military Aviation. The triumphal trip of Jiménez and Iglesias in 1929, had left out of their route Paraguay, Bolivia, Colombia, Venezuela, Costa Rica, Honduras, El Salvador, the Dominican Republic and Puerto Rico, while Cuba had already been visited and it had been, in fact, the last stop for the flight of the “Jesús del Gran Poder”; but Barberán’s project, to fly from Spain to Cuba and Mexico, to return via New York was not a simple sporting feat nor a political embassy, it was more than that. It was precisely, for the opening of a route, and like it happened in the times of the “Flotas de Indias” (Fleets of the Indias -As the Americas were called then-) during the XVI, XVII y XVIII centuries, Havana continued to be the center of that enormous zone of influence that covered all the countries bordering on the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea, and was called upon to become the port of arrival for all the air transportation companies to the Mesoamerican area, that is, what in the present time technical language of aerial transportation, is called a Hub… And I’d say, that Barberán was not far from the mark since now, in the early XXI Century and despite the fact that the range of present day airliners could allow in any case, a direct flight, and Miami at just 70 miles from Havana, is the great hub, the great crossroads and interchange location for all the airlines that operate between Europe and the Central zone of America and those that operate between North and South America, and that future, which is now a reality, was in the imagination of Mariano Barberán during that night between the 10th and the 11th of June, 1933 in the middle of the Atlantic.

Joaquín Collar meanwhile, grasping the airplane’s controls works hard at maintaining the heading and the balance of the “Cuatro Vientos”, compensating for the fuel consumption from the different tanks in order to avoid any instability due to a shifting of the center of gravity… Everything had been calculated, but it was necessary to follow the plans to the dot… Keep the engine running an 1,795 RPM, take fuel from tank A. Ten minutes later, close the valve on the tank A, and for another ten minutes, feed the engine with fuel from tank E, and this way, continue to alternate the use of both tanks until they were completely emptied. From that point on, the switching would be between tanks B and D. And not to forget that when one deposit was emptied, its ventilation valves must be opened. The same valves which, in an emergency would be used to effect a quick emptying of the tanks, but now they were used for ventilation, thus eliminating the gasoline vapors that could have been left inside the tanks and whose existence always carried the grave risk of an explosion.

Meanwhile, Berberán continues to reminisce about past events… The High Command had approved his project and so too, had the Government. Last October -just nine months ago- Construcciones Aeronáuticas had received the order to build the airplane. The Getafe plant was enthusiastic about the project and promised to have the airplane ready in six months. Mariano Barberán had a series of meetings with the factory’s engineers and had indicated what he needed to get from the airplane: Range of 8,500 kilometers without refueling; this was the primary objective. All the others (speed, ceiling, communications and so on) should be subordinated to the former… And the engineers and technicians, and the workers at the Getafe plant, kept their word. And even when they proposed to him the option of installing a radio-telegraphy system or loading 25 more kilograms of fuel, Berberán, despite of being an enthusiast of telecommunications and perfectly aware of their value and possibilities, opted for the additional fuel… That’s why they were now isolated, without communications, in the middle of the ocean.

Doubtlessly, the physical and psychological fatigue caused by the thirty three hours enclosed in the narrow cockpit of the “Cuatro Vientos” were beginning to take their toll in Mariano Berberán’s spirit, the same way they had affected Joaquín Collar, fifteen hours earlier. But what was now happening to Barberán, was even worst. It was not a manifestation in the form of a stomachache, but instead he was beginning to doubt his own calculations… What if the wind had been stronger than what he had estimated? What if they had drifted to the South? With only a three or four degree deviation to the South, they risked passing by but without seeing them, the minuscule Virgin Islands and they would pass South of Puerto Rico, deviating to the central area of the Caribbean, without a possibility at all of reaching their destination… On the other hand, Collar had just passed him a message, and he did not like it one bit. Fuel consumption was higher than their estimates.

Barberán makes then a decision… He orders Collar a change of heading. From the 256º they had been following since leaving Seville, they now steer to 270º, due West… This way, he is sure of coming upon one of the Great Antilles or in the worst case, assuming that the drift had taken them Northwards, the coast of Florida… He will start now, frantic and hurried, his calculations for the new heading and based on the new circumstances… Shortly thereafter, he passes a piece of paper to Collar, in which he has drawn the Island of Santo Domingo and marked on it, the Bay of Samana, in the Northwest side of the island, and a nervously written note: “to become visible within three hours… And curiously, it will happen like that… Three hours of feverish waiting but finally they can see, on the port side and far away what seems to be an islet, half covered by clouds… There is an exchange of notes between the two aviators. Joaquín Collar believes that he can identify it as Tortuga Island; Barberán bets for the Samana Peninsula, whose narrow isthmus seems to be covered by the clouds, giving the impression that it is in reality, an island.

When they get closer, they can verify that Barberán was right. Although Joaquín Collar knows Barberán very well, is astonished at the precision of the calculations of his navigator. From now on, everything will be easier, much more easier. The flight is now visual, following a heading that parallels the North Coast of the Santo Domingo Island and maintaining an altitude of about 1,200 meters until in the end, when they have been flying for about 38 and half hours, they cross the Cuban coast at Guantanamo. It is now 14:00 hours (Cuban time) and the date is June 11, 1933. Over Guantanamo they descend to an altitude of about 700 meters. Then, they fly around and over the city until they are sure that they have been seen and identified and then continue their flight in the direction of Havana.

Telephone calls are placed from Guantanamo to Havana, reporting the passing of the airplane… Everything gets in motion in the Cuban capital. Don Luciano López Ferrer, Spanish Ambassador goes to the Campo Columbia aerodrome, where the “Cuatro Vientos” is scheduled to land. Three airplanes from the Cuban Military Aviation take off to meet with the airplane near Santa Clara, in the center of the island, and then they will escort it to Havana (in one of them, as a guest, flies the Spanish Military Attaché, Capitan Don Francisco Vives Camino, and in another, Sargento Mecánico Modesto Madariaga, member of the working team of the “Cuatro Vientos.” Half an hour later, when the airplane has been flying for thirty nine hours, it is reported to have flown over the city of Victoria de las Tunas…

Now that the goal is within reach however, onboard the airplane, other type of problems are beginning to happen… Collar again, passes a nervously written note to Barberán: “Fuel remains for about two hours.” It is now 15:10 local; they have been flying for 39 and a half hours and they have just over flown Camagüey… Ahead, in the central part of the island, between them and the city of Havana, threatening storm clouds can be seen. If they are forced to fly around them, they won’t have enough fuel to make it to the Capital… Barberán takes a prudent decision: He passes a note to Collar, in which it says: “Turn back, we’ll land in Camagüey.” Down below, the inhabitants of the village of La Florida, see how the “Cuatro Vientos” overhead, reverses its heading. It is now 15:20, local time. Ten minutes later, when they have been flying for thirty-nine hours and fifty-nine minutes, Joaquín Collar, under a light rain, softly lands the “Cuatro Vientos” on the Pan American Airways aerodrome near the Cuban city of Camagüey. Mariano Barberán’s dream, the non-stop aerial link between Spain and Cuba, has just been achieved.

There are barely any people waiting for them in Camagüey. Only two Lieutenants from the Cuban Aviation Corps -deployed to that aerodrome (as there were in all the other aerodromes in the island) to try to help the Spanish aviators in case of an eventual landing there- the four soldiers guarding the field, and Walfredo Rodríguez, a reporter for the Associated Press, and only newsman present in the field. They were the only ones who actually witnessed the landing.

When the airplane stopped, Barberán first, and then Collar, climbed down from the “Cuatro Vientos”, tired and cramped from almost complete immobility inside the narrow cockpit… Collar with emotion, hugs the airplane: “You did good!” were his first words upon hitting the ground. After this, and before anything else, they check their fuel tanks. They had only about one hundred liters left, barely enough for fifteen more minutes of flight time.

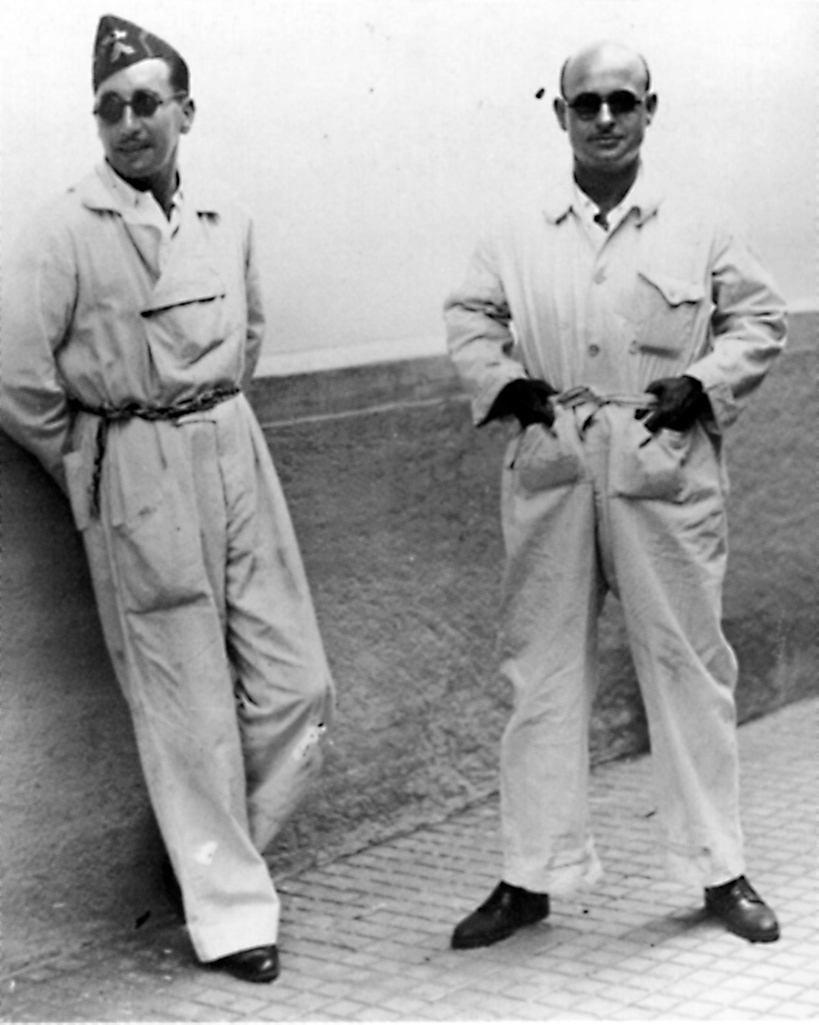

Almost immediately, Colonel Pedro Vilato, Chief of the Camagüey Military District, arrived at the airfield in an automobile. He informed the Spanish aviators that he had already cabled Havana notifying them about their good landing in Camagüey and placed himself at their disposition. Barberán and Collar are not bashful. They know that the next day, they must take off from this place, to head towards the Capital, and they want to get to know the lay of the airfield. They use Colonel Vilato’s automobile to drive up and down the length of the field, until they have recorded in their memories each detail, each depression, each ondulation of the terrain… Later, and only after the technical aspects had been taken care of, they head for the Hotel Camagüey. Still wearing their light gray flight coveralls, they will arrive at the hotel, where they will await for Madariaga’s arrival, which will have to make the airplane ready before it can take off again. After a refreshing bath, Barberán and Collar crash on their beds, to enjoy a few hours of a well-deserved rest.

Meanwhile in Havana, the news of the landing in Camagüey has been received. The next day, the airplane will not make it all the way to the Capital. The airplanes that had gone to Santa Clara to escort the “Cuatro Vientos during its last kilometers of flight to La Havana, return, only to have two of them take off again, this time to Camagüey. In one of them, piloted by Cuban Aviation’s Teniente Alonso, travels as a passenger Capitán Don Francisco Vives Camino, Military Attache to the Embassy of Spain. The other airplane, piloted by Cuban Military Aviation’s Teniente Yánez, carries as a passenger Sargento Mecanico Modesto Madariaga, who is carrying with him the cranking handle and the compressed air cylinder, necessary for the starting of the engine, the next day. He also carries other spare parts he has considered that could be needed.

As soon as these aircraft land in Camagüey, Madariaga gets to work on the “Cuatro Vientos.” He checks the landing gear suspension, because of all the weight it had to carry during the take off in Seville, and finds it to be in excellent conditions. He checks the controls and steering devices, and finds them to be also in excellent conditions. Starts the engine and listens carefully, but finds nothing abnormal. With real care, he greases joints, replenishes the oil tank, refills the gasoline tank and only then, when the airplane is ready to take off again, goes to the Hotel Camagüey to meet with Mariano Barberán and Joaquín Collar.

It is now 9:00 PM, only five hours since the “Cuatro Vientos” had landed in the field in Camagüey when Mariano Barberán and Joaquín Collar -after warmly embracing Capitán Francisco Vives and Sargento Madariaga at their room in the Hotel Camagüey- appear in public. The Hotel’s salons are full of people cheering them. A banquet has been organized -the first in a long series- to celebrate them. The local authorities and the Spanish Consul will attend. Despite their extraordinary level of fatigue, Barberán and Collar will still have to go, after the banquet, to a party that the Spanish colony has organized in their honor. To the fatigue of their travel, they will have to add their attending these parties, dressed in their regulation uniforms, made in a thick fabric, completely inadequate for Cuba’s tropical weather. Barberán and Collar however smile proudly, aware of the extraordinary valor of their feat and what is even more, of its meaning for the air transportation in the future. The protocol acts keep going seemingly forever and it won’t be until past midnight when the Spanish aviators will be able to retire to their rooms to rest, but not before ordering that they should not be waken up before nine. Madariaga returns to the airfield, and continues checking on the airplane. His airplane. He doesn’t want to leave anything to chance. Suddenly, he discovers something terrible: the main fuel tank, the gigantic Superbidón with a capacity of 3,900 liters, is cracked and it is leaking fuel… Maybe this is the reason for the excessive fuel consumption that Joaquín Collar observed during the last hours of their transatlantic flight and that he, worried, had told Madariaga about… Same comment that had prompted the mechanic to go back to the airfield that night, to check the airplane one more time. It is just a crack, a small crack in the welding of one of the joints of the metal plates that conform the fuel tank and join it to the fuselage… It must have happened not too many hours ago, since otherwise, they would have lost all of the fuel onboard, and besides, they had been lucky that they had no fire onboard, since the lower fuselage was literally soaking wet with gasoline.

Madariaga cleans and dries the area the best he can and attempts, without success, to seal the crack… It became impossible to fill the main fuel tank under these circumstances.

The next morning, the three Spanish aviators meet to deliberate on the situation. Making it to Havana poses no problem; they can achieve this by using only the fuel from the secondary tanks located in airplane’s upper wing, while leaving the gigantic main tank, empty, but it would make it impossible for the airplane to undertake the second stage of their trip, between Havana and Mexico City, without first making complete repairs to the main tank. There would be hard work to be done in Havana, and plenty of it.

At 14:10 hours, Barberán and Collar, wearing the regulation blue uniform of the Spanish Military Aviation, climb on the “Cuatro Vientos.” Earlier, by telephone, they had been briefed about the situation and meteorological forecast for the route Camagüey – Havana. At 14:22 the “Cuatro Vientos” and the two Cuban airplanes that will escort her, take off, the Cuban airplanes also carrying Vives and Madariaga.

Meanwhile, the Columbia aerodrome in Havana is filling with people. The guests and the official reception committee are located at the Escuela de Aviacion’s buildings, in the hangars, on the observation terrace… The Cuban Military Aviation Chief, Capitán Mario Torres Menier and his officers went to great lengths to tend to the personalities invited to the act. The Secretary of the Interior Doctor Zubizarreta, the Spanish Ambassador Don Luciano López Ferrer, the Chief of the Army General Lores, together with representatives of different groups and Spanish Associations in Havana, all are there. So are too, and just by coincidence, the Spanish Military Aviation Captain Francisco Iglesias Brage, one of the heroes of the “Jesús del Gran Poder”, who is in the Cuban Capital on his way to Colombia… Some airplanes take off to go and meet those coming from Camagüey… At 16:45 local time, the “Cuatro Vientos” and the airplanes escorting it, over fly the periphery neighborhoods of Havana. At 17 hours, 15 minutes and 30 seconds, the landing gear of the “Cuatro Vientos” makes contact with Campo Columbia’s runway. The airplane, once on the ground, heads to the hangar area. When the engine’s power is reduced, Barberán and Collar can hear the roar of the multitude, which cheers them… Finally, they stop.

The first to make it to the “Cuatro Vientos” is Sargento Mecánico Madariaga, who just a moment earlier, has climbed down from the Cuban military airplane that brought him from Camagüey. Immediately after, Capitán Mario Torres Menier, Chief of the Cuban Military Aviation, together with some of his officers… Orders are issued: A group of soldiers position themselves around the airplane, to protect it from the multitude that running, is coming towards it…

From the “Cuatro Vientos” cockpit, comes the smiling face of Barberán in his blue uniform, sweating under the tropical sun… With help from Madariaga, he jumps to the ground. Then, the smiling face of Joaquin Collar shows up, who waves nonstop, as a salute… And jumps to the ground. The soldiers open a path to the Aviation School buildings. There, the first person Barberán and Collar will meet, is Jesuit Priest Father Gutierrez Lanza who, with his reports and studies on the meteorological conditions of the Caribbean region, has been of extraordinary help for them, in the preparations for their flight… Afterwards, the authorities, the ambassador…

They are invited to address the public through the microphones. Berberán, serious, full of emotion, will say: “In view of the extraordinary reception we are having, I cannot help it but to say just a few words: Long Live Spain! Long Live Cuba!” As proof of their distinct personalities and attitudes towards life, Collar’s words will be completely different. He approaches the microphones, relaxed, smiling and winking to those surrounding him. His words are also concise. To the amazement and surprise of the authorities present there, he yells: “Long live the beautiful Cuban girls!”

The enthusiasm breaks loose, and this was the beginning of a week of craziness. From Columbia, they will be taken to the Casino Español, where a wine will be offered in their honor. From here, they will go to the “Diario de la Marina”, where they will address the multitude filling the adjacent streets. From the offices of the Diario de La Marina, Barberán and Collar will have telephone conversations with the President of the Spanish Republic, Don Niceto Alcalá Zamora, and also with their own families. From the “El Diario de la Marina” they were taken to visit other newspapers: “El Mundo” and “El País”, as well as other institutions. They were able to retire to rest, at last, at a late hour, after a day full of emotions. Meanwhile the Havana’s City Council, in an extraordinary meeting, accorded to confer to Mariano Barberán and to Joaquín Collar, the City’s medal.

The next day, June 13th, Barberán and Collar will be received with identical enthusiasm, in the Cuban Department of State, and from this place they will be taken to present a floral arrangement at the monument to Jose Martí, father of the Cuban Independence. A new visit follows, to the Banco Comercial de Cuba, to the Banco Gelats, to the National City Bank. In this last place, they were given a prize of 500 dollars, prize that the aviators donated for charitable purposes including the Fund for the Repatriation of Immigrants. They also visited the Asturian Center and the Center of the Business Clerks of Havana. During the night, the Committee of Spanish Societies of Havana, offered a banquet honoring the aviators… On Wednesday June 14th, they received honors from the City of Havana, in a ceremony held in the imposing location of the Plaza de Armas, where they were given a medal, and the keys to the city. Afterwards, there was a banquet in their honor, offered by the newspaper “El Pais.” And during the night, as a relaxation, a fishing trip in a yacht.

The flight of the “Cuatro Vientos” has had repercussions outside of Spain and Cuba. The Mayor of Chicago, and the “Chicago Tribune” begin inquiring both in La Havana and Madrid, to have the airplane and its pilots, on their flight back from Mexico, to go to Chicago, before heading to New York and to attend as honored guests to the International Exposition “A Century of Progress” already in progress in that North American city. Meanwhile, Barberán and Collar will receive more recognition in honor of their feat: On Sunday the 18th in Havana at the Cervecería Polar, at the Club Hípico, at the Club de Aviación de Cuba, at the Círculo Militar y Naval, where they will be awarded the “Medalla al Mérito Militar de Cuba” (Cuban Medal to the Military Merit.) And finally, a great popular act to honor them, in the National Theatre of Havana. Later, that same Saturday night, they will attend Balls in the “Centro Gallego”, and will also go to the one at the Association of Commercial Clerks and the one in the Castillian Center of Cuba.

On the 19th, the last of the tributes will take place in the Hotel Nacional. Barberán is committed to leave Cuba. So many honors and parties are causing more fatigue in them, instead of easing the rest and recovery they need, while they still have in front of them a good portion of their trip. Barberán is decided to return to Spain, flying. It was also necessary to repair the airplane and to prepare with much detail their next stage, between Havana and Mexico City.

Regarding the repairs to their airplane, Joaquín Collar y Mariano Barberán feels at ease. They fully trust the capable Madariaga and he had available all the material, technical and human resources from the Cuban Military Aviation. On the 18th, Madariaga advises Mariano Barberán and Joaquín Collar that the “Cuatro Vientos” has been repaired, and it is ready again, to take flight. As for the preparation of the next stage of their flight, they don’t have any problems. The route between Havana and Mexico City is being constantly flown by airplanes from Pan American Airways, with intermediate stops in Mérida (Yucatán) and Veracruz, and pilots from this company will advise Collar and Barberán regarding the best way to execute their flight. They advise them to fly very early, before the sun’s heat allows the formation of tropical cyclones. They advise them to fly only during the wee hours of the morning and to make an intermediate stop in Veracruz, where it would be advisable to wait until the next morning before taking flight again… Regarding the route, no problem there: visual flight following the coast until Veracruz and between Veracruz and Mexico City, also a visual flight following the railroad tracks that join both cities. Barberán agrees to everything with one exception, and this is with regards to completing the flight in two stages. He would rather complete the route directly, improving into what the Pan American pilots did weekly. If he had been able to cross the Atlantic, a flight of a mere 1,700 kilometers between La Havana and Mexico City was nothing as would also be the next stage, because meanwhile, orders from Madrid had arrived and they had been instructed to include Chicago in their return trip from Mexico to New York.

Everything is ready… At 20:42 on Monday June 19th, through radio station CMC Mariano Barberán bids farewell to the Cuban people, thanking them for their kind attentions that the Spanish aviators have received during their stay in the island. At the same time in Mexico City, preparations begin, for their reception. Their arrival to the Balbuena aerodrome is estimated to be between 13:00 and 14:00.

During the early hours of the morning of June 20th, Barberán and Collar are getting ready to leave the world of reality and to become a legend… A fine and persistent rain causes strange reflections on the buildings at the Havana’s aerodrome of Columbia. Once in a while like a knife, the beam of a beacon cuts through the darkness. The “Cuatro Vientos” at rest, glimmers under the hangar’s lights… A solemn silence encompasses everything. At this early hour, few people have come to witness the airplane’s take off. A meteorological report is received. It informs them that, with the exception of light rain in the Havana area, the weather is fine along the route toVeracruz, and the same is also true for the flight between Veracruz – Mexico, but in Mexico there was the possibilities of thunderstorms during the afternoon.

The early morning is not good, under the rain. Madariaga has spent the night next to the airplane. The field is covered with puddles, practically underwater, but the take off is still considered possible. The General Consul of Mexico in Havana, arrives. It is now four-twenty in the morning. Barberán and Collar get up, have breakfast and then get dressed. Barberán wears his blue uniform and over it, he is wearing a thick turtleneck white jersey. Collar has decided to wear on top of his uniform, a maroon flight jacket. They head for Columbia.

The latest conversations between Barberán and Collar have been regarding their route and have generated small disagreements. Barberán pretends to fly to Villa Hermosa, in the State of Tabasco, and once there, depending on the situation, they will decide whether to fly to Veracruz so they will then follow the railroad tracks to Mexico, as the Pan American pilots had advised or, they would head directly to Puebla and the City of Mexico, seeking the shortest but also the riskier route. Collar, being more conservative would rather fly to Veracruz… The relationship between the two of them seemed tense. Something had happened between them… They had planned on leaving Havana on Thursday 22nd but Barberán has decided to move their departure date by two days. Barberán was not well. A furuncle in his arm, which had needed draining, was causing bouts of fever… Collar looked as if he was upset about something… Both showed signs of fatigue and tiredness.

Barberán and Collar arrive at Columbia at 04:30 in the company of the Chief of the Cuban Military Aviation, Capitán Torres Menier. Barberán heads to the meteorological observatory to receive, from Teniente Riveri and from Padre Gutiérrez Lanza, the latest meteorological forecasts, while Collar receives from Madariaga the observations he considers pertinent regarding the work he has performed on the airplane… Good weather is expected until Veracruz, but from Veracruz to Mexico City, the forecast is alarming. A signal systems has been arranged: if when overflying one of the airports in their route, they observe signs made with red flags, this will mean that ahead of them the weather will not allow flight to continue and it should be understood as an indication for an immediate landing.

A milky dawn begins to show up from the East. Daylight is almost there… Collar, riding in an automobile, goes up and down the field, recording in his mind, every puddle, every depression on the ground. The “Cuatro Vientos” is pulled out from the hangar, and it shines under the lights and the fine rain that continues to fall… At 05:45, Mariano Barberán and Joaquín Collar take their respective positions in the cabin of the “Cuatro Vientos”. One minute later, Sargento Mecánico Modesto Madariaga connects to the engine, the compressed air cylinder that is needed in order to start it, and after completing all the necessary checks, Joaquin Collar starts up the engine… Seven minutes later, when the engine reaches its operational temperature, the “Cuatro Vientos” takes off from the waterlogged Columbia aerodrome, and climbs at the same time it describes a wide left side turn, and heads West, until it gets lost in the horizon.

At 08:15, Mexico time, and after one and a half hours of flight, the steamer “Lezcano”, which was navigating through the Strait of Yucatán, sends a radiogram, indicating that the “Cuatro Vientos” has just overflown them. At 08:50, the airplane’s passage is reported over a place named Distas, near the Yucatan’s capital of Mérida. Twenty minutes later it is spotted over Ticul, and three quarters of an hour later, at 09:55, it flies over Chapotón, on the coast of the Gulf of Mexico. But the airplane is behind schedule. It is late, the sun is beginning to heat the air up, and big storm nuclei are beginning to form.

At 10:45, the “Cuatro Vientos” overflies the Ciudad del Carmen aerodrome, on the Gulf Coast. It comes down low, and circles… Red flag signals are made from the ground, weather is worsening… It looks like the “Cuatro Vientos” is getting ready to land, but suddenly, the airplane climbs again, and resumes the same heading it had been following. Almost an hour later, at 11:35, its presence is reported -it has been heard, but not seen- over the city of Villa Hermosa, in the State of Tabasco, right on the Tehuantepec Isthmus, where Mexico narrows between the Pacific Ocean and the Caribbean Sea… Five minutes later, an airplane from the Compañía Mexicana de Aviación, a subsidiary of Pan American, flying from Veracruz to Mérida, crosses in the air with the “Cuatro Vientos”, reportedly seeing it from afar, or believing that they have seen it… Fromm then on, there will be no more news about the airplane.

Expectation meanwhile in Mexico City, is great. Towards noon, thousands of Mexicans begin arriving to the Balbuena aerodrome, there to receive the “Cuatro Vientos.” Viewing platforms had been purposefully built, and near midday, they are completely full; several military bands continuously played the best of their repertoires, alternating between Mexican, Cuban and Spaniard music. Balbuena has become an impromptu party to honor the “Cuatro Vientos” and its crew. Near one thirty, a squadron of Mexican military airplanes takes off an head to meet the “Cuatro Vientos” and to escort it to Mexico City. From the Northwest, a threatening storm front is advancing. The personalities invited, begin arriving at Balbuena around two in the afternoon. Loudspeakers announce the arrival of each one of them, and they are received with applause from the crowd. When the Spanish Mission, headed by Ambassador Álvarez del Vayo arrives at two-thirty, the reception on the part of the public is pure delirium, the clapping and the shouting of “Long Live Spain”, are endless… Shortly thereafter, the Mexican authorities arrive, headed by the Secretary of State, who is representing the President… Only the “Cuatro Vientos” has to show up yet.

At four in the afternoon begins falling over Balbuena aerodrome and the City of Mexico one of the most powerful storms in memory. Heavy rains and strong wind gusts make the presence of the public at the airfield almost impossible. While the guests shelter themselves in the hangars however, the public attending remains there, waiting for the “Cuatro Vientos.” The situation changes at five in the afternoon. There is no news from the airplane. The public begins to become worried. The face of the Spanish Ambassador shows signs of preoccupation. In the official tribune, the guests and the Diplomatic Corps begin to show pessimism. The Ambassador of the United States, in an attempt to raise the spirits, makes a joke: “Columbus came over water, and the ‘Cuatro Vientos’ will do it under the rain…” He says. No one laughs. The bands have stopped playing. At six thirty , the storm stops and good weather begins to show up again… Telephone contact has been made with different places alongside the route. It is confirmed that the last contact was Villa Hermosa. Since then, 11:35, nothing else is known. The Mexican military airplanes return at seven. They have some difficulty landing, the ground is dotted with water puddles, but luckily, there are no accidents. They have no news from the “Cuatro Vientos.” They did not find it. They have diligently explored the routes between Mexico City and Veracruz, between Mexico City and Puebla, without finding any signs of the presence of the airplane.

At seven-thirty in the evening, the public starts heading back for their homes, slowly, with a sensation of bitter sadness. At eight, when the flying time allowed by the fuel onboard has been more than exhausted, the Mexican Government, on a request from Ambassador Alvarez del Vayo, gives the orders to initiate a search operation… In Balbuena, the aerodrome remains lit, as a show of a futile hope… Sargento Mecánico Modesto Madariaga, tears in his eyes, continues waiting.

June 21st dawns with an extraordinary display of activity. Thirty eight airplanes from the Mexican Army, besides some other civilian ones and more than ten thousand soldiers and civilian volunteers, will search for the next coming days, the areas through which the airplane could have flown, but without managing to find any trace of the “Cuatro Vientos” or its crew. Important rewards are offered for those who provide information… Many people come forward seeking the reward, but in the end, they will be deemed to be false witnesses.

The search is really exhaustive. Several hypotheses are followed. Contradicting testimonies begin to appear… On June 21, the operator of the lighthouse in Puerto Frontera, Tabasco, claims to have seen lights out to sea that could very well have been distress flares. Several launches went out to sea on search missions, without finding anything. On June 22nd, an airplane flown by the Mexican aviation ace, Colonel Roberto Fierro and Sargento Mecánico Madariaga will fly various possible routes the airplane could have followed, beyond Córdoba and Orizaba; they will scout the slopes of the “Cerro de La Malinche,” -where local residents claimed to have seen an airplane fall- but without success. More thorough searches will be organized. The territory is divided in twelve sectors, which are carefully searched. The Government of Guatemala joins the search, alongside the border zone with Mexico. From June 21st through to the 30th, the search is methodical but fruitless… while at the same time, the press publishes hopeful news, purported findings, which have to be denied later.

On July 13th, when Madariaga is getting ready to head back to Spain, important news arrives. In the place called Barra de Tupilco, located just South of Puerto Frontera, in Tabasco, a pneumatic chamber has been found; it could possibly have belonged to the “Cuatro Vientos.” It is sent by sea to Veracruz, to be sent from there, to Mexico City. Madariaga is asked to stay, to try to identify it. When the pneumatic chamber arrives, it is demonstrated that it is Spanish-built, at the Pirelli factory in Manresa, but Madariaga cannot assure that it is one of those the “Cuatro Vientos” was carrying to be used as life savers in case of need. Besides, the place it was found, had already been left far behind by the “Cuatro Vientos” in its flight. Yes, it is possible that sea currents could have taken it to the beach where it was found, but it is not a conclusive proof.

The Spanish Government sends Comandante Ramón Franco to conduct, with the help of the Mexican Government, an official investigation… The results of which, will not be definitive at all, concluded that the “Cuatro Vientos” probably crashed at sea, but there is no material proof to support this conclusion, as there are no proof to support the multiple testimonials that keep coming in. The fate of the “Cuatro Vientos” and its crew becomes a mystery.

Eight years later, in 1941, a new version of events begins to become public… Mexican reporters from the “Hoy” magazine -among which Edmundo Valadés was especially of note because of his investigative work- published the news that the “Cuatro Vientos” had crashed in Mexican territory, specifically in the Mazateca Mountains, bordering the States of Oaxaca and Puebla, and that local indians had murdered the Spanish pilots to steal their belongings… Valadés provides numerous testimonies, but not a single item of material proof… This thesis continued to gain credit, to the point it warranted an investigation from the police in the State of Puebla, without any results that could permit to reach definitive conclusions. The thesis is brought back to life soon after, by the Spanish writer Jose Luis León Depetre in his book “La Tragedia de México” (The Tragedy in Mexico) and re-taken again in 1947 by Alfonso Serrano Illescas, from the “Excelsior” newspaper… In 1955, and beginning with the second printing of Leon Depetre’s book (the first printing would not get to be known in Spain), the then Teniente Coronel Serrano de Pablo will adopt the same theory, in an article published in the magazine “AVION” of which he is then, the director, and in 1964 in an article published in the Sunday supplement of the Newspaper “Ya” in Madrid… In Mexico, Fernando Aranzábal, a reporter, re-takes the issue for the “Excelsior” newspaper.

In 1973, Jesús Salcedo, a Mexican reporter for Channel 13, begins an investigation on the mystery. He is convinced, a priori, that the theory already mentioned: that the “Cuatro Vientos” crashed in the Mazateca Mountains and the indians murdered the crew, hiding the bodies and the remains of the airplane, was the most accurate one. What Jesus Salcedo will do through many years, is to find proof to support his theory… In 1984 he travels to Spain, and has meetings with the High Command of the Military Aviation, pretending that they will fund his investigation… No agreement is reached. The already Teniente General Serrano de Pablo, who has taken part in some of the meetings with Jesús Salcedo, proposes during a speech in Granada, that an investigative commission should be sent to Mexico, conformed by Coroneles Herrera Alonso and González Betes… The idea of Teniente General Serrano de Pablo will not become reality in the end. In 1992, Jesús Salcedo publishes again the theme in the “Ovaciones” magazine… He describes how he has picked up some metallic parts and bone fragments in a cave next to “La Guacamaya” village, near Matzatzongo, in Puebla, and he claims them to be from the “Cuatro Vientos” the former, and from the crew members, the latter. Laboratory analysis carried by the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México in 1995, prove that the metallic pieces are from iron that has completely decomposed into Goethite as the result of a very high temperature and high levels of humidity. As always, we are in a situation where these could be the remains of the “Cuatro Vientos” but the proof is not absolutely conclusive.

In 1999, our friends Enric Pallarés, Jordi Bautista, Tomás Blasco and Ricardo Millán, members of the Associació d’Amics de l’Aeronàutica del Prat de Llobregat, would conduct the first Spanish expedition to search for the “Cuatro Vientos.” They traveled to Mexico and investigated in the terrain. They have covered the Mazateca Mountains and have visited the “La Guacamaya” village, where Salcedo places the tragedy; they have spoken with people from the location. Their conclusion is the same: the proof is just circumstantial. There is no definite proof. The stories of witnesses, now indirect testimonies, since all of those who could have been direct witnesses in 1933, have died, are repeated time and again the same way, re-telling something that has already become part of the popular culture of the area, and has reached the level of a legend. We are still in front of one of the unresolved mysteries in Aeronautical History, or perhaps, as I like to believe, Mariano Barberán y Tros de Ilarduya, the scientist-aviator born in Guadalajara, and Joaquín Collar Serra, the precise pilot born in Figueres, followed the same fate as others like Manuel Colomer, Charles Mungesser, Jean Mermoz, Amelia Earhart, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry… The fate of the heroes, of those whom a romantic German poet used to say, do not die, but softly vanish in the air and become forever, a part of the memory.