Lieutenant Colonel Dell Toedt, born in Laurel, Iowa, in 1930, is a veteran of the Korean War where he flew P-51s with the 45th Tactical Reconnaissance Squadron out of Kimpo Air Base, managing to complete a hundred combat missions before heading back to the United States.

Between 1953 and 1957, Lt. Col. Toedt had the good fortune to do some flying in Latin America, ferrying F-47s, F-51s and T-33s from the U.S. to Ecuador, Peru, Chile, Guatemala and Costa Rica, while assigned to several USAF Ferrying Squadrons. What follows is the first of a series of articles depicting his adventures “down south” where he flew complicated missions, got involved in more than one risky situation and had the time of his life.

In April 1954, I was transferred to Kelly AFB, at San Antonio, Texas. I was still flying a lot of P-47s and P-51s as well as F-94s, F-86s, T-6s and an occasional L-19 Bird Dog. Then, in late July 1954, I got a call at home one Sunday morning to get to the base to go south immediately. It was a classified mission so they said, don’t even tell your wife.

The mission was to deliver three P-51s to Guatemala in time to help hold the country down after Col. Carlos Castillo Armas and his Liberation Army had invaded it, ousting President Jacobo Arbenz from power. Major Rusty Wilson, Captain Don Red Ryder and I were flown to Brooks AFB, about 15 miles from Kelly AFB, to pick up the three fighters from the 182nd National Guard Squadron. Previously, I had flown several airplanes in for them from Luke AFB, and I knew that they had top-notch maintenance.

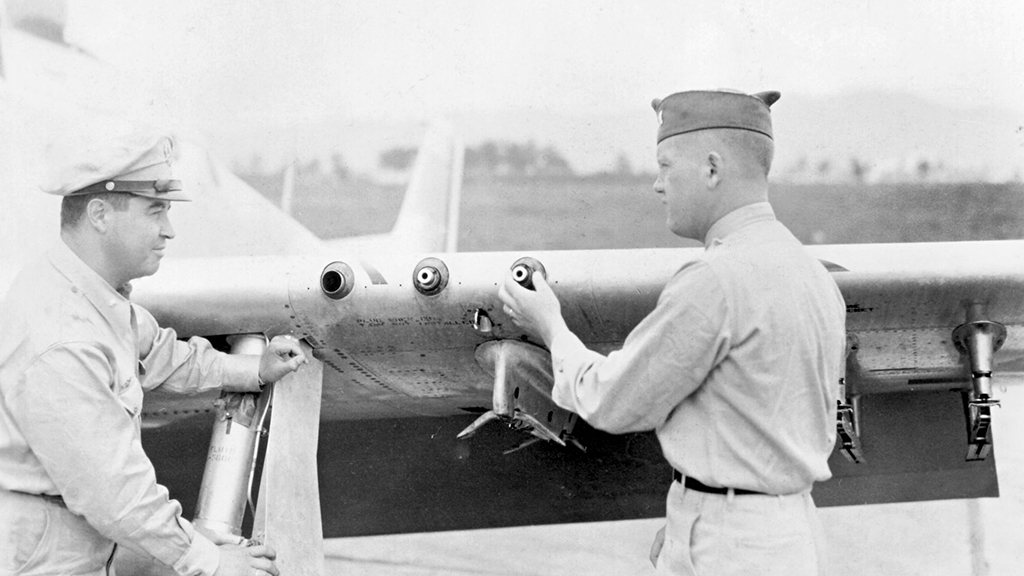

When we arrived at Brooks, we found out that the three Stangs had their machine guns fully loaded and that their internal tanks were filled to the top. The drop tanks were empty though. A couple of hours later we flew them to Kelly, which was a port of “Demarcation.” Our orders were to make Mexico City that same night and go into Guatemala City the next morning.

During our pre-flight briefing, the wheels of the Ferrying Wing ordered full tanks on our planes. As expected, we complained because it would mean landing late at night and very heavy at high altitude (Mexico’s altitude is 7,850 ft MSL.) To make things worse the wheels, in their infinite wisdom, made us fly an hour locally to get familiar with the airplanes, even when the three of us were high time P-51D pilots, with at least 100 combat missions in one war or another. It was until late in the afternoon that we took off for Mexico City. Rusty was leading, Red was on one wing and I was on the other.

Mexico seemed the Milky Way on that dark night. We arrived around 2200 and put the planes on the ground at a pretty high airspeed considering the altitude and the gross weight we had with a lot of extra fuel and ammunition. A C-54 with 50,000 rounds for our machine guns was there ahead of us. As soon as we tied our mounts down the fuel truck arrived and began to refill them. In the mean time, Rusty sat down to figure out our flight plan to arrive in Guatemala City at 0800.

We took off from Mexico City at 0200, under a pitch black sky and circled until we were at 15,000 feet in order to clear the mountains that were there, all around us, but that we couldn’t see. We would dead rekcon southwest until daylight, hit the Pacific Ocean coast, and follow it down to Guatemala. We had on board four VHF four-channel radios but there weren’t any navigational aids. And as it turned out, we had no radio communications with anyone until we reached Guatemala City about 6 hours later.

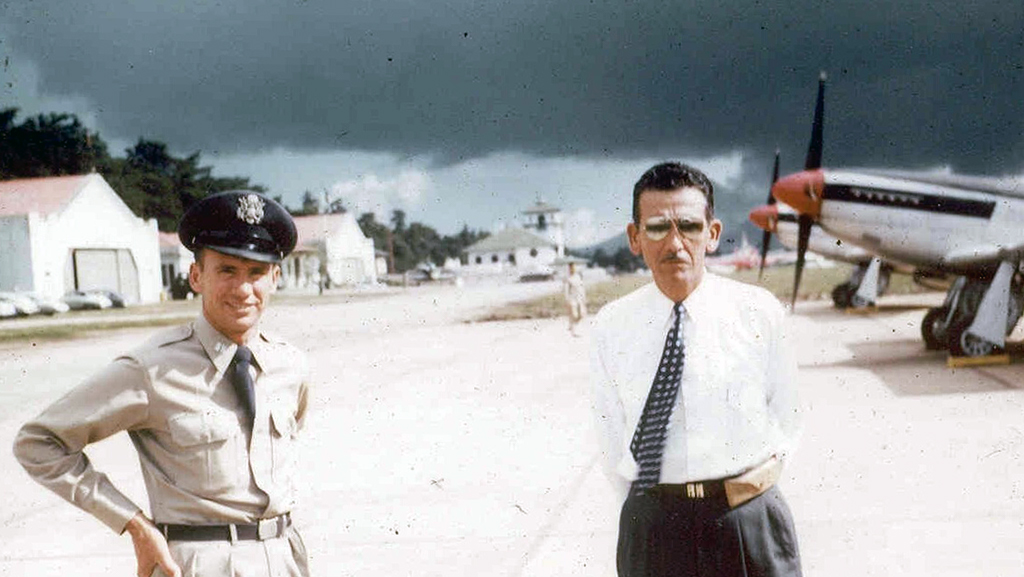

Arriving in Guatemala we were greeted by Lt. Col. Rodolfo Fito Mendoza, who introduced himself as the Minister of Air for Guatemala, but in reality he had been the chief of Col. Castillo Armas’ Liberation Air Force. As we found out later, he had two brothers who had been appointed head of the Army and chief of the Secret Police, respectively.

For some reason, Fito kind of took me under his wing, and I rode around with him and his young son in his Cadillac. He had gone through the USAAC flying school in 1929, and his instructor was 2nd Lt. Nathan Twining, later Chief of Staff of the USAF. The Revolutionaries had put a price on the head of Fito’s son, who was about 9 years old, and Fito kept him with him all the time. He gave me insights to the revolution I never knew, but most of them were lost when my notes disappeared on one of my house moves.

Fito had guns all over that Cadillac, and one, a small colt semi automatic, I admired very much. Fito said: Would you like it? take it! I didn’t, and have always regretted turning down such a memorable souvenir. A few days later I regretted not having a weapon even more…

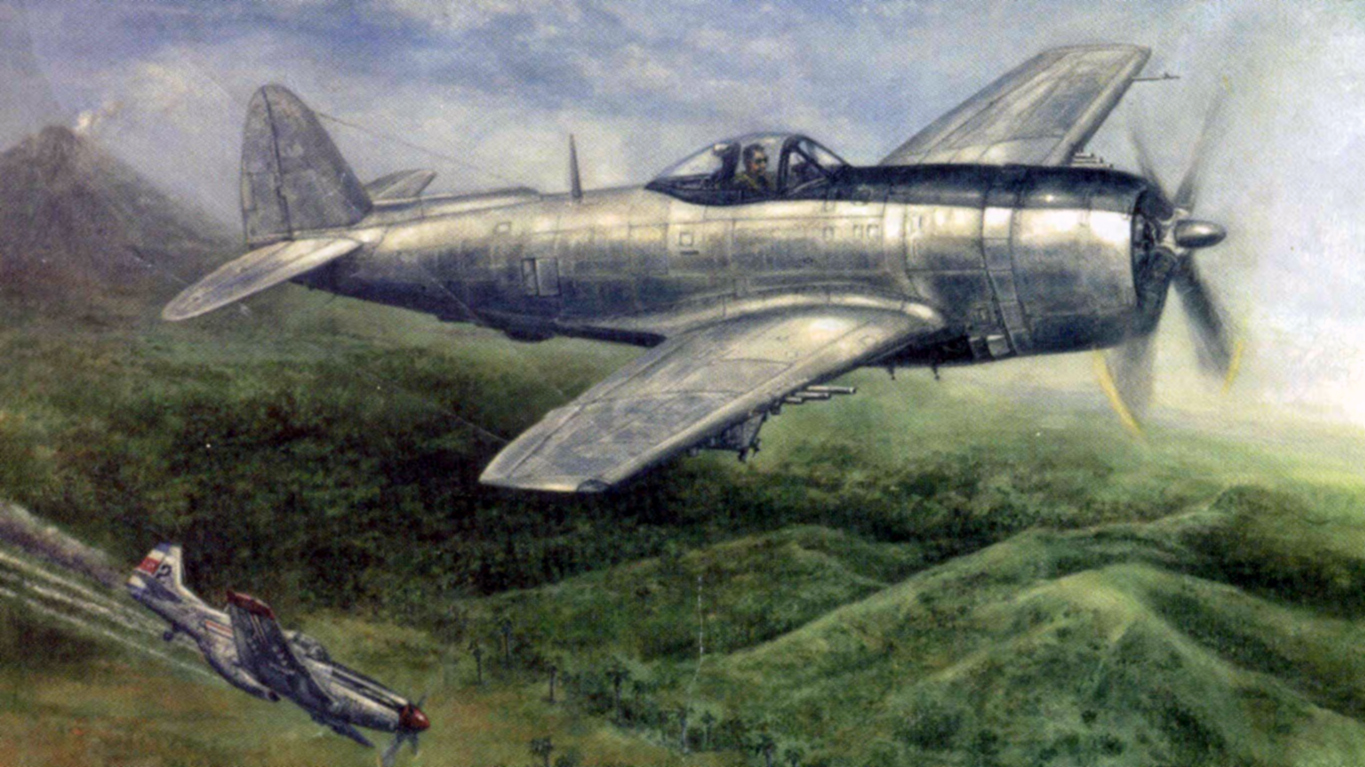

Another person I became very friendly with was a mercenary who had acted as the chief of pilots for the Liberation Air Force: Jerry Delarm. Jerry and I got along very well, and he told me about some of his escapades and took me out and showed the P-47N that he had used during the invasion. I could still see faint paint marks “PRANG” which showed its ancestry, the Puerto Rican Air National Guard. It also had several bullet holes patched with what looked like aluminum cans.

As we were walking around admiring his Jug, I noticed that Jerry carried a government-issued Colt .45-semi automatic pistol in his belt at full cock. I asked him if he always did it that way, and he said he did, because there were lots of people who would kill him if they had the chance. At the time, the USAF Mission in Guatemala was headed by an astute Colonel named Earl Batten, who disliked Delarm very much, to the point of describing him as a psychopathic killer on one of his reports. However, my relationship with Delarm was friendly, at least up to that time.

Days later, President Castillo Armas ordered a victory parade to celebrate the overthrow of Jacobo Arbenz. The three of us, P-51 pilots were invited to be in the reviewing stand, right behind the president at the tribune in Campo de Marte. It was a big celebration. Jerry was in the air in his Jug, and made some extremely low, high speed passes over the crowd.

After the parade we went back to our hotel, and I went out in the streets. The Liberation Army, in their rubber-tire sandals, machetes, and machine pistols had taken over the city. On its part, the Guatemalan people had switched from supporting Arbenz to supporting Castillo Armas, and there was a fiesta mood everywhere.

At some point, I went into a bar and ordered a beer. A man sitting next to me asked me if I was a pilot. He was about 6’ 4’’ wearing a brown suit and brown tie. I said I was, and he pulled himself up and said I too, am a pilot and I thought: Sure, everyone is a pilot now. So I asked him what he flew. Focke-Wulf FW190s and Messerschmitt ME109s he said. I was a Luftwaffe pilot in WWII.

So I began to ask him about the planes characteristics to try to determine if he knew about them, and he seemed to. So I told him that a relative of mine, Fritz Todt, had been Hitler’s Chief Engineer, and had built the West Wall, the Autobahns, and the Siegfried Line. He ran the Todt Organization. When I told him that, I got the same treatment I have received all over the world from Germans: Comrade!!! He said and threw his arms around me.

It turned out that his family, of German extraction, had gone back to Germany from Guatemala to visit just before the start of WWII and at the conflict’s outbreak he had gone in the German Army. He had been a machine gun commander on the Soviet Front. Now he was a beer salesman in Guatemala, so I bought him beer and listened to his story.

We would set up our machine guns on the front, and the Russians would send in 500 men to take our position, and we would kill them. And they would send in 1000 men, and we would kill them. Stupid, bullshit Russians!!! Then they would send 1500 more and we would fall back…

So he applied for flying school and after graduation, he was posted to an ME 109 squadron. Trying to find out his background I asked him if he had ever heard of the Abbeville Kids, the best Luftwaffe squadron that did a lot of damage to our bomber streams. He said no. I asked him if he had ever heard of the Yellow Nose Messerschmitts, (I was referring to the same squadron; they had to have a certain number of kills to get the yellow nose on their airplane.) He said no again. However, he mentioned that he had been squadron commander at Abbeville, and his squadron had yellow noses.

Then, he pulled out a big, old leather wallet, and dug down in the bottom where he found a picture of him, young, with a long leather coat, a Sam Browne belt, and a Lager pistol in front of an ME109. He said: I don’t show this to everyone, but since you are a Todt…

At some point of our conversation the German pilot mentioned that he had gone to President Castillo Armas to offer his services for the new Guatemalan Air Force. The president replied that if he enlisted he could be a mechanic. That offended him immensely and he referred to the entire invasion as Stupid bullshit Liberationist. I was buying him beer, and he was going back to the men’s room periodically, and as he went he would knock the Liberation Army troops out of the way with a smashing forearm, saying Stupid bullshit Indians!!! I stayed as long as I thought it was safe, and probably too long as I think back on it, and I left as he was going to the men’s room once again.

I went back to my hotel, and went to bed. At about 0600 the next morning there was a frantic pounding on my door. It was Colonel Batten, saying: get up!!! We have to get to the airport fast!!! And as he drove us, he briefed us on the situation: Since 0300, the cadets of the Guatemalan Army Academy were attacking the Liberationists at the Roosevelt Hospital, where they were temporarily based.

In a desperate attempt to route the Liberationist out of the country, the young cadets were beating the hell out of the Castillo Armas’ troops. Jerry Delarm somehow got word, and got in the air in his P-47 and started strafing them. Our mission, for incredible that it may seem, was to get in the air and shoot Jerry down. (The Guatemalan Air Force commandership, seeing the cadets’ courage had decided to support them, and tacitly, the USAF Mission obliged too.)

As we pulled up to the flight line where our Mustangs were parked, several Army troops with sub machine guns ordered us to stop, and not move to our planes. They thought we were going up to help Jerry, so they lined us up against a stone wall, and were prepared to kill us. Colonel Batten, who was known and held in high regard by the troops that guarded La Aurora Air Base, did some palavering with the officer in charge of the armed group, who in turn told us that if we could get off the field in 20 minutes we could go, but if we couldn’t, then we weren’t going. Whatever that meant, with a bunch of guys pointing at us with sub machine guns and the three of us standing in front of a stone wall, it didn’t look good.

By that time the crew of the C-54 had been brought to the field, there was a scramble to get the plane ready for takeoff. No flight planning, no pre-flight check, just a rush to get it in the air and everyone was helping. We didn’t know what had happened to the 50,000 rounds of .50 cal ammunition we had for our Mustangs, but at that point we really didn’t care. In a matter of minutes we were off the ground, and as we left I looked back at what looked like a beautiful, peaceful valley, that in reality was a God damned battle ground where they were shooting the heck out of each other.

One of our mechanics had bought a huge stalk of bananas, and that was what we had to eat on the long flight across Mexico, back to San Antonio.

At the time of our arrival in Guatemala, that country’s Air Force still had in service three Boeing P-26 fighters, and I must confess that they were in prime shape. The Guatemalan pilots had told us that when we had checked them out in the Mustangs they would do the same for us in those classic aircraft. Our abrupt departure killed that wonderful opportunity, and I have always regretted it.

Something I’ve been chastised for years was that I didn’t take a lot of pictures during this trip. But, that was almost 50 years ago, and I was a lot younger then. To be honest, it all seemed just a normal day’s work and nothing exceptional that I needed to save with pictures. (I hope Dan Hagedorn isn’t reading this!!!)

Stangs for Costa Rica

After we returned from Guatemala Rusty Wilson and I went back to ferrying P-51s, P-47s, F-94s, F-86s L-19s, or whatever was moving. Capt. Don ‘Red’ Ryder was transferred, and I never heard from him again.

On a Sunday, late in the morning, about a year later, in July, 1955 the phone rang, and I got another phone call from ferry control that said get out to Kelly AFB as soon as possible. I asked where we were going this time, and I was told it was classified.

Gloria, being a typical Air Force wife, followed the tradition of asking minimal questions and drove me to the Squadron at Lackland AFB in our 1952 Ford convertible. She left me at squadron ops without any knowledge of the events unfolding or my destination. At that time, we had two young children at home. Our son D.C. was two years old, and his sister Martha was one. Gloria was expecting our third child. To put things into perspective, our third baby, Elizabeth, is now an airline Captain, retired as a U.S. Navy Commander with 12,000 hours of pilot experience, 200 successful landings on an aircraft carrier, and most notably, a former commanding officer of a Navy jet squadron.

The situation mirrored our previous experience during the journey to Guatemala. The State Department had made assurances to the Costa Rican government that four armed P-51s would be ready for combat in the capitol San Jose by 0800 the following morning, to assist in thwarting the invading forces advancing from Nicaragua, supported by the dictator of that country, General Anastasio Somoza. Hence, we were going in with ‘hot’ guns, full ammunition, and no instructions. The diplomatic niceties of who we could and should shoot were missing, and we were on our own.

Upon returning home, my wife switched on the television and to her surprise, our story unfolded before her eyes. The news coverage detailed our urgent need to be in Costa Rica by the following morning, showcasing footage of us preparing our Mustangs, which had been provided by the 182nd squadron of the Texas Air National Guard. Guiding us through the preparations was my trusted friend, Captain P.D. Straw, who later achieved the rank of Major General, but at the time, held the position of squadron leader at the 182nd. We were glad to be getting these airplanes from the ANG because they always kept them in excellent mechanical condition. These P-51D might have been the same that I had flown into the Guard two years earlier from Luke AFB.

Once we were ready to depart, the big thinkers in the Wing headquarters had to make their mark on an otherwise excellent planned mission: Mostly multi engine pilots, they insisted that we take both full internal, and full drop tanks to fly to Mexico City.

Captain Rusty Wilson, who had 100 missions in Mustangs in Korea, had a lot of experience in Latin America and was fluent in Spanish, was leading. I was on one wing and Lt. Mac McCullough was on the other. Mac had flown 100 missions in P-80s in Korea, and had a lot of Mustang time, but was the kind of guy who could fly anything. Our fourth pilot was Captain Bob Strait, who had accumulated substantial flight hours in P-51s during World War II. The C-54, with Colonel ‘somebody’ at the controls, which was carrying 50,000 rounds of .50 cal ammo for us, had already left when we were authorized to takeoff. However, by insistence of the ‘Wing Weenies’, we had to fly local for an hour before starting for Mexico City. In the end, we were allowed to leave, but by that time it was getting dark. I don’t recall much of this flight, but I do remember that it was a ‘map in the lap’ navigation in the middle of the night. By the time we arrived over Mexico City, the night was pitch black, even with all the lights of the city. At that altitude, and as heavy as we were with full ammunition and all the fuel left over from our flight from San Antonio, we were landing ‘hot.’ Two of us got on the ground on the first approach, and the other two took a couple of tries.

It was almost midnight when we got the Mustangs refueled and tied down. We had to leave Mexico City at 0300 for a 5-hour flight to San José. One of our group, who shall remain nameless, (not me, by the way) looking up at the pitch-black sky, said if he was leaving at 0300 he was not taking off sober. So, for about 3 hours waiting for takeoff time, we sat in the bar at the airline terminal, having a few beers while flipping peanut shells over the wall on the table where the Colonel was sitting. He was livid; so much he could hardly speak, but at that point he was not in control anymore. He finally stalked out of the bar, fired up his C-54 and departed for Costa Rica, so he could get to San José before us.

About 0200, we did go out and lay down under the wing of our planes for a few minutes, then did our walk around inspection and then we fired up those big 1600 HP Rolls Royce engines, and taxied out for takeoff doing it in an ‘S’ because we couldn’t see ahead over that long nose on the Mustang. As expected, the surroundings were engulfed in complete darkness, just as we had been informed. And there we were, venturing into a combat zone without the essential briefing on potential threats, lacking a reliable map, and armed with only a four channel VHF radio and an outdated radio range receiver from the 1930s, which proved to be largely ineffective as Central America lacked radio ranges.

The four of us had accumulated a combined total of over 400 combat missions, which made the situation seem less extraordinary at the time. However, reflecting on it now, after many years, it highlights the value of wisdom and caution that comes with age. It also reinforces the notion that fighter pilots are typically younger individuals. At the time, I had recently turned 25 and was often the youngest pilot in our Wing. Being chosen for a mission of this nature was a tremendous honor. Recalling my experiences in Korea, where I had successfully engaged and destroyed two tanks, numerous weapons, a significant number of trucks, and even a trench filled with enemy troops, it felt gratifying to be once again engaged in a combat mindset.

The plan entailed ascending in a circular path over Mexico City, gradually gaining altitude until we reached 15,000 feet, following the same approach we had taken during our journey to Guatemala. Rusty Wilson was climbing above me, while I was looking down, watching Bob Strait, who was lower than me. Then, the flame from his exhaust stacks went out, and he called that he had lost his engine. I said to myself,’there goes Bob.’ There was a long silence, and then I saw the exhaust stacks light up again. Shortly after, Bob said ‘I’ve got it going‘ and he began to climb up to meet us at 15,000 feet. The sky was so pitch black that it was unbelievable, and all we could see of each other’s aircraft was precisely the exhaust stack flame and the faint navigation lights on the wings. Minutes later, we had climbed high enough to miss the surrounding mountain peaks.

Considering the current focus on flight safety, it is highly unlikely that our flight plan would be approved in today’s standards. However, during that night, we were essentially improvising and operating without a detailed plan right from the start. We would dead reckon, or just kind of make a best guess in a south-west direction until we hit the pacific coast, which should happen about

daylight. Then, we would follow the coast line down to a valley with a large river, and fly up the valley to San José. We had been ordered to fly across Nicaragua, as a show of strength to where the insurgents were coming into Costa Rica, but it was too complicated for our limited navigation resources, and we headed straight for San José.

Deep down, I had a strong intuition that it must be Jerry Delarm, my old friend from our time in Guatemala, who would be engaged in such an operation as a mercenary pilot. With this in mind, I volunteered to remain airborne, claiming to have enough fuel. My intention was to trick Jerry to make an attack, as I knew that the P-47 Thunderbolt, with its turbo supercharger, excelled at altitudes above 30,000 feet. On the other hand, the Mustang was a superior aircraft at lower altitudes. Additionally, I harbored a desire to engage in combat with Jerry, if circumstances allowed.

With full power engaged, I armed my six .50 caliber machine guns and ascended to 15,000 feet, circling the field at a high cruising speed for approximately 15 minutes. Throughout the maneuver, I remained vigilant, constantly checking my rear for any signs of Jerry’s presence. However, Jerry did not make an appearance. Consequently, I began a gradual descent to 5,000 feet and informed the tower of my intention to land. Even at this lower altitude, I kept a watchful eye, half-expecting Jerry to emerge over a hill, searching for me in the landing pattern as I approached with my landing gear and flaps deployed. Yet, disappointingly, Jerry remained elusive.

The weather was scorching hot and humid, causing the sun’s rays to intensify within the cockpit, creating a greenhouse effect. Consequently, the temperature began to rise significantly. One aspect worth noting is that the Mustang, unlike some other aircraft, lacked air conditioning. It relied solely on fresh air for ventilation. However, in this instance, the fresh air circulating was hot, offering no relief from the heat. To cope with the situation, I detached the hose that directed fresh air onto the windshield from its mount. Then, I unzipped my flying suit from the bottom and inserted the hose inside, attempting to create a cooling effect. Although the improvement was minimal, it did provide some relief.

I made a pretty tight pattern, and have to admit I had some ominous passing thoughts about Jerry catching me on final approach with the gear and flaps down, but there wasn’t any problem. After I landed and was directed into the stacked up sandbag revetments where the other 3 Mustangs were parked. Then, the crowd was permitted to approach the aircraft. Seizing the opportunity, I climbed up onto the wing and enthusiastically greeted the gathering, shouting ‘Buenos Días‘ while waving to them.

A TV cameraman pointed his camera at me and asked me to do it again. I happily obliged and repeated my enthusiastic wave and greeting, shouting ‘Buenos Días’ once again. It turned out that the cameraman, a weathered veteran of numerous conflicts, was acquainted with my uncle Jack, who had worked for 20th Century Fox News in the 1930s. In any case, my actions were captured by the camera and later broadcasted on nearly every television channel in the United States that night. There I was, standing proudly on the wing, waving and shouting, with my flying suit partially unzipped from the bottom. Yet, fortunately enough, not a single person seemed to have noticed this particular detail.

As I made my way down from the airplane, a young Costa Rican pilot swiftly jumped onto the wing. Leaning into the cockpit, he eagerly inquired about how to activate the guns. Then, he said that he was going after Jerry. He knew the mercenary pilot quite well, since they had flown commercial airlines together some years earlier. It turned out that Jerry had strafed a town one noon, wounding some kids and a little girl. ‘I have to get him‘ he said. I showed him how to operate things in the cockpit; he thanked me and, unexpectedly, removed his wings from his uniform, presenting them to me as a token of appreciation. I have those wings on my desk as I write this. Some time after we, the U.S. pilots, had left Costa Rica, the Mustang that that young Captain was flying, mysteriously crashed. It was the same P-51D that I flew into San José, the same one that I showed him how to turn on the .50 cal. machine guns. Years later, Jerry Delarm admitted that he had slid in behind the Captain’s Mustang and shot him down before he was unaware that he was under attack.

Sneaking up behind an unsuspecting pilot, is indeed a method commonly employed by assassins. It is worth acknowledging that in similar situations during our time in Korea, we also resorted to similar tactics when given the opportunity. In the high-stakes environment of combat, where the consequences of inattention can be severe and even fatal, it is understandable that Jerry, being a mercenary, did what he was paid to do. The world of soldiers of fortune seldom adheres to principles of chivalry or honor.

Many years later, Jerry told me that General Somoza personally had sent him down to San José to kill all four of us in the pattern as we landed, but the reason he didn’t come down and attack us was that he had expended all his ammunition earlier, during strafing runs on various government positions. I told him he was a ‘Goddamn liar‘ and that he couldn’t have shot me down, and if he had attacked me while I was flying top cover, the other three Mustang pilots would have been coming up after him like a swarm of hornets. He claimed that he had a racing engine in his jug, and it would pull 60 inches of manifold pressure under full throttle, and that would have made it a really interesting air battle. The Mustang would pull 61 inches, while the Jug normally pulled only 45 inches at takeoff. When I knew Jerry in Guatemala, he was having big-time maintenance problems with his P-47 so I take his claim of racing engines with a grain of salt. But you couldn’t believe Jerry in almost anything he said, and now he is dead and there is no way to further the discussion.

What is interesting is that when I knew Jerry in 1954 he was slim and handsome; he had dark black hair, a very small, well trimmed mustache, and wore Army pink dress pant, a white shirt and an AF Leather flying jacket with an Army .45 in his belt. One day when he was showing me his bullet-riddled Jug, I mentioned that the .45 in his belt was at full cock and that if it went off, he would lose some very essential private parts. He said there were people who would kill him if they had the chance, and that his .45 was ready to be used with no delay. From what I have learned from an article years later, his nickname was ‘El Sulfato.‘ He was known for playing the guitar, and singing love songs in cafes. The last picture of him, taken probably in the late 1990s, showed an evil, misshapen thug. He had huge hands, which I could see probably had been turning wrenches on many an engine that he was going to take into a war zone where getting home had a high priority.

I always regret that there wasn’t an opportunity for Delarm and me to engage in combat, with him piloting the P-47 and me in the Mustang. Or was it just to prove which one of us was better? I think I was better, and bet my life on it!

The last time I ferried an aircraft down south occurred in 1957, when I brought one of the first Lockheed T-33s to the Batista government, in Cuba. Curiously, three years later, that same jet was involved in the defense of the island nation, during the Bay of Pigs invasion. But that is a story for another day…

These notes, originally published in December 2005, comprise the third delivery of a three-part series of articles. Lt. Col. Dell Toedt, who passed away on 21 November 2009, is fondly remembered, and in tribute to his memory, we are finally making these notes available to the public once again. You can read part 1 by clicking here, and part 2 here.