Lieutenant Colonel Dell Toedt, born in Laurel, Iowa, in 1930, is a veteran of the Korean War where he flew P-51s with the 45th Tactical Reconnaissance Squadron out of Kimpo Air Base, managing to complete a hundred combat missions before heading back to the United States.

Between 1953 and 1957, Lt. Col. Toedt had the good fortune to do some flying in Latin America, ferrying F-47s, F-51s and T-33s from the U.S. to Ecuador, Peru, Chile, Guatemala and Costa Rica, while assigned to several USAF Ferrying Squadrons. What follows is the first of a series of articles depicting his adventures “down south” where he flew complicated missions, got involved in more than one risky situation and had the time of his life.

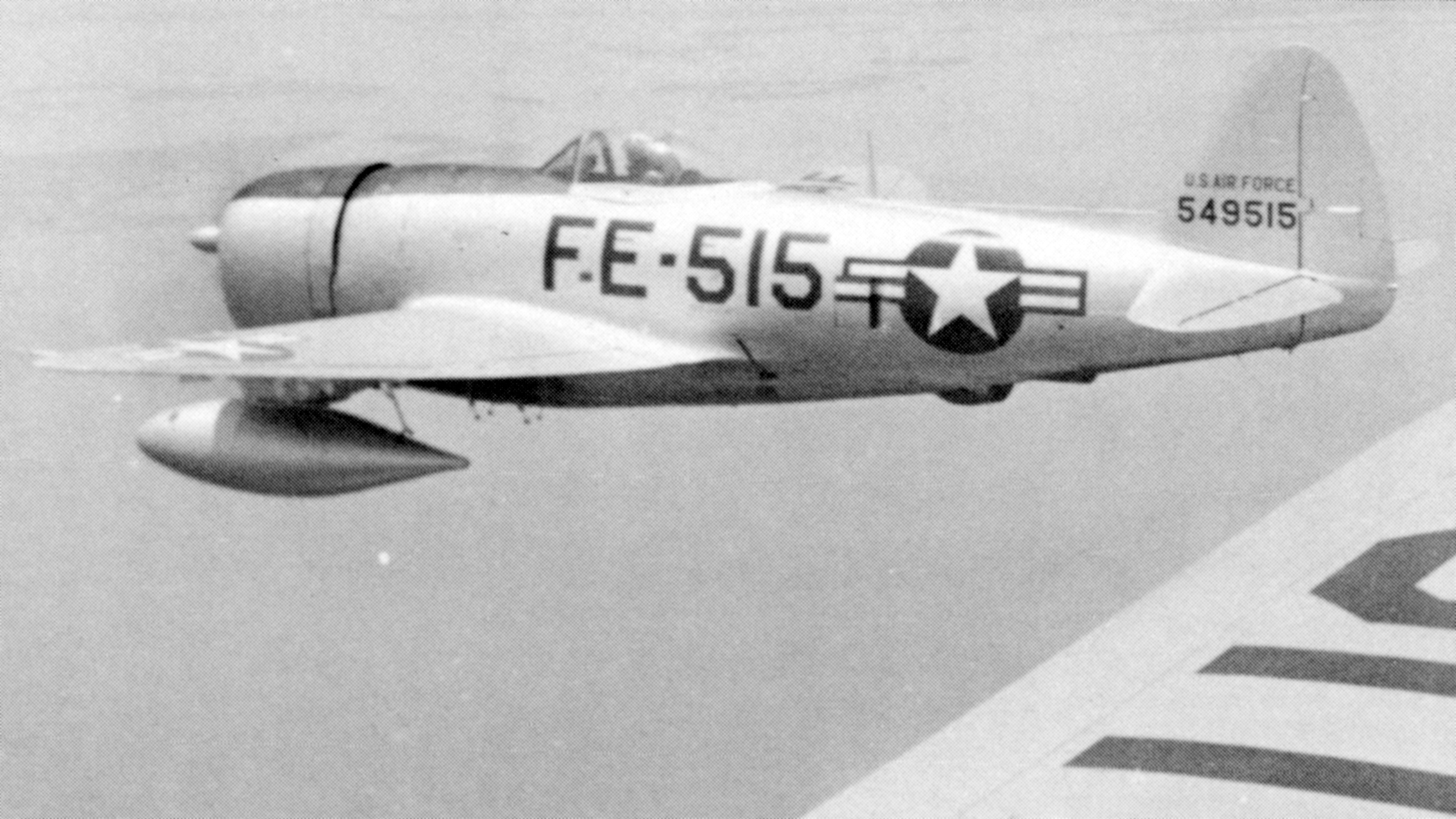

My first trip “South of the border” occurred in the summer of 1953. Our mission on that occasion was to ferry several Republic F-47Ds to their respective recipients, those being the air forces of Ecuador, Peru and Chile. As I recall it, twenty-four young pilots, a Douglas C-54 for maintenance, and a Douglas B-26 for navigation, converged at the TEMCO plant located at the Hensley Naval Air Station in Dallas, Texas, where everything was being readied for our departure. Initially we would go to Kelly Air Force Base in San Antonio and from there to Panama Canal Zone, via Miami and Jamaica. Once in Panama, we would deliver our fighters to their respective countries.

Some of us had a lot of flying time in the Jug or the Mustang but others were multi-engine pilots who had been pressed into service in the very last minute and their experience was nil to say the least. Many of them were a bit anxious as they performed the walk-arounds. Even so, things were going fine up to that point and everyone’s airplane checked out well… Except mine!

Minutes later all the jugs and the supporting planes departed for Kelly AFB, leaving me behind to have my plane fixed. It was until later that day that I managed to take off. It was one of those murky, hazy afternoons with poor visibility, and as I was heading for San Antonio, the Cherry Hill radio tower, located south of Dallas, suddenly appeared in front of my propeller. I rolled up on the right wing, somehow missing the guy wires supporting the tower and slid past with just a few feet to spare. It was piece of cake for a fighter pilot, right? Didn’t bother me then, but years later, I knew I had been lucky…

The mood at Kelly AFB was happy and light-hearted. Our F-47s had been reconditioned by TEMCO. They had drop tanks, so we had plenty of fuel. Additionally, we had a C-54 packed full of spare parts and mechanics, and a B-26 with a navigator to keep us on course. The C-54 even had several cases of C-Rations in case of emergency. What else could we ask for? However, none of us had the slightest idea of the problems that would develop before we could deliver the last of the F-47s to the new owners.

The next day we departed for Miami. It was a very long but uneventful flight. Those of us who were ordinary line pilots had a room at a low rent beachfront hotel on Miami Beach, but some of the wheels seemed to be elsewhere. We didn’t care. We were getting $9.00 a day to pay for our room and food. The weather was good, and life seemed to be kind to us.

However, after two weeks in Miami, we began to wonder why we didn’t head south. A newspaper reporter published a story about us, showing some of the pilots standing in the swimming pool having a tray of drinks delivered. Someone sent a copy back to our headquarters and the group leader was summarily fired. He apparently was having a great social whirl while the rest of us were sitting around. A senior Captain, named Bill Redeen, was assigned as the new group leader; he formed us up and headed us for Jamaica in no time. However, he apparently hadn’t checked the weather well, because a hurricane was also headed for Jamaica at the same time as we were.

About the time we started to cross over Cuba we met these towering black clouds that formed the front edge of the hurricane. Things did not look good for proceeding to Kingston, so the flight plan was changed immediately, and we turned back west and headed for Campo Columbia airport at Havana.

The instructions from the tower at Campo Columbia were explicit: DO NOT LAND. We orbited for quite some time, hopelessly waiting for the tower’s authorization. Finally, Lt. Bill Morris informed the group leader that he was dangerously low on fuel and that he was going to land. Somebody in the frequency said “You are going to start a war” and Lt. Morris replied “I don’t have any bullets!” As Lt. Morris rolled in for landing, we all went behind him. Minutes later everybody was on the ground safely.

It turned out that the Cuban government was on high alert because they had been advised that the island was about to be invaded on that particular day. After some talk, we were all parked and tied down because the hurricane was coming toward Havana.

Somebody arranged hotel rooms at the Hotel Nacional, a very nice hotel, and a bus was brought up to take us downtown. My buddy, Rusty Wilson and I picked up our clothes bags from the C-54, and with some foresight, also one of the cases of C-Rations that were being carried for emergencies, the emergency being that Rusty and I only had a few dollars after our long stay in Miami Beach, so we knew we would be eating in.

I had a chess board in my bag, so before the hurricane hit, we very judiciously used our few dollars and bought a large bottle of that good Cuban rum, a dozen fresh limes, and a few bottles of Coca Cola, and for a week, while the hurricane pelted Havana, Rusty and I sat in our room drinking rum and Coke, eating C-Rations heated in the sink and played chess.

As the hurricane subsided, we began to venture out during the evenings. One night we were strolling around, and wound up in front of the National Theater. Several long, black limousines pulled up and several men in white dinner jackets jumped out with sub-machine guns, and spread out in front of the building. After they had deployed all around the entrance, Generalissimo Fulgencio Batista got out of one of the limousines, and started into the theater. Rusty, with his droll sense of humor, said in a loud stage whisper “Tiene usted la bomba?” to what I replied “Rusty, you dumb shit, are you trying to get us killed?” He thought that it was funny. It might have been the rum and Cokes, I guess.

For the next 4 or 5 hours, Rusty and I walked around Havana, going in bars, talking to people, singing with them, and having a good time. I had studied Spanish in college, and it was coming back pretty quickly. Rusty on his part was fluent in Spanish, taking up the role of translator. The next day, when we told the Air Attaché people what a good time we had, they turned white and said that we had gone through the most dangerous part of the Havana’s malecon, and that we were lucky we didn’t get killed.

After about 2 weeks the weather cleared and we managed to crank up our Jugs for the flight to Kingston, Jamaica, where we were headed before being diverted by the hurricane. In no time all twenty-four of us were taxiing, trying to get lined up with our flight leaders. I was near the takeoff runway, and was forced off the taxiway by another aircraft, and my left wheel went deep into an ant hill that had been softened by the 2 weeks of rain.

I shut down and stood on the wing, waiting for someone to come and pull me out. One of our F-47s lined up on the northwest takeoff runway about 50 yards from where I was stuck, and I watched him take off. About the time the pilot pulled the gear up I saw a puff of black smoke coming out of the cowling, then the engine quit, and the plane went down straight ahead. Several of us ran and commandeered a pickup truck in which we sped to the crash site as fast as we could. The plane, flown by Lt. Bill Morris, had gone down inside a dog track on the northwest corner of the airfield, where he hit the ground and then went through a wall made of concrete block about 8 feet high, taking a section of it about the size of the Jug’s wings. The engine was ripped off, and the fuselage was lying in a drainage area with 145-octane gas pouring out of the main fuel tank and making a big puddle about 10 feet wide. Lt. Morris was nowhere to be found; however, the cockpit was intact, and the canopy was open.

Lt. Morris said later that the last thing he remembered was turning off the magnetos as he hit the ground. A couple of seconds later six Cubans pulled him out of the cockpit, threw him in a taxi, climbed in the aforementioned vehicle –all six of them- and took him to the hospital. Lt. Morris was rolled up in a ball in the corner of the taxi with his rescuers sitting right on top of him. It was a miracle that he wasn’t killed or paralyzed during that taxi ride. But the Cubans took action, and you have to hand it to them for that.

The Havana hospital had a great surgeon who specialized in back injuries and had trained at the Mayo Clinic in the US. He put Lt. Morris on a long, flat steel strip that was mounted between a large vise-type machine. The doc would bend the machine, take an x-ray, and keep doing that until Lt. Morris’ back was aligned again. Then the doc put a heavy cast over his entire body, let it harden, and then pulled the steel rod out of the cast.

Lt. Morris lived to fly again, but while he was in the hospital, he became the darling of many of the Cuban ladies, including a couple of proposals of marriage. Being already married, he had to decline those most delightful proposals. He received wonderful care from the Cuban doctors, without which he surely would have died, or been crippled for life.

But let’s get back to our story: Having jammed the heavy F-47 landing gear into the mud changed something in the retraction mechanism, because a few days later, when I took off, the gear fairing doors closed first, and the gear retracted on top of them. I immediately learned that the F-47 does not climb in that configuration and I was staggering around under full throttle, trying to gain some decent altitude.

For a while, I recycled the gear, but the fairing doors always closed first, and the gear retracted on top of them. In the end I decided to land and, fortunately, the gear did come down and locked safely. The Cuban Air Force’s mechanics had some experience with the F-47 and said they would re-time the gear retraction. As this was being done, the entire group returned to Campo Columbia, since they didn’t want to leave me behind.

The second attempt to reach Kingston was successful; however, when we tried to take off for Panama the weather got on our way again and we were forced to return and stay in Jamaica for a week. I don’t remember the name of the hotel in which we were accommodated, but it was an old building with a lot of class and a very relaxed atmosphere. The automobiles that took us to the hotel were 12 cylinders Cadillacs and Lincolns; big, open cars that carried about 8 people, and the drivers raced all the way to the hotel. It was one of the most exciting things of the entire trip. I guess the drivers were trying to show a bunch of fighter pilots how fast they could go.

I loved Kingston, and the couple of nights we went out, invariably we would go to the Glass Bucket where Lord Flea and Lord Fly were entertaining. I ran into Lord Flea years later in Miami, and he claimed he remembered the bunch of F-47s heading for South America.

One night we were advised that a local organization had arranged a social meeting for us, and we were all bussed out to a very nice hotel. It turned out that in the social meeting were a lot of very nice young ladies also. There was music and dancing. I don’t dance, so I sat and talked to a nice young lady named Ursula. When I returned to California a couple of months later, there was a card from her, which my new fiancé has asked pointed questions about for many years. My conscience is clear, but I can’t vouch for any of the other guys. They were all very attractive, proper young ladies.

The day after the social meeting, we were scheduled to fly to the Panama Canal Zone. We briefed, took off, but the weather report came in after we were airborne. The tower guys said that the weather en route to Panama had gone bad, and that we should return to Jamaica as soon as possible. Taking that good advice, the group returned to the island, but several of us flew around, just enjoying the Jamaican scenery. In the process, we buzzed a couple of fishing boats, and may have been a little too low because the crews jumped overboard.

I was flying on Mac McCullough’s wing, as we went in to land. We were landing out of a loop, but Mac failed to inform that to me; I only found out when his landing gear came out in my face as we were upside down. I made a very smooth touchdown on the runway, but as I was slowing down, the right wing slowly dropped as the gear on my Jug collapsed. It was in that way that I found out that the retiming job that the Cubans had performed hadn’t gone that well. I thought about trying to jab the plane up with torque, like you could do with the Mustang, but the speed was too slow so I just stood on the left brake trying to keep the jug straight.

attempting to reach the Panama Canal Zone but weather got in the way. (Photo: Lt. Col. Dell Toedt.)

I slid for about 1,500 feet down the runway, spewing 145-octane fuel out of the right drop tank, and by a miracle it didn’t catch fire. Just before it stopped the gear and tank dug in, and the plane did a 90-degree spin onto the grass. I opened the canopy and threw my helmet up in the air. Across the tarmac came all of our pilots, running as hard as they could and seconds later they helped me out. The F-47’s propeller was bent and the bottom of the drop tank was worn. Aside from that there wasn’t much damage.

My little mishap made it to the newspapers and I became a minor celebrity for a couple of days until I took another airplane and left for Panama. As I was taking off, I thought that this was going to be the last time that I would have to fly over the Caribbean, however, time would prove me wrong.

These notes, originally published in December 2005, mark the beginning of a three-part series of articles. Lt. Col. Dell Toedt, who passed away on 21 November 2009, is fondly remembered, and in tribute to his memory, we are finally making these notes available to the public once again. You can read part 2 by clicking here, and part 3 here.