It’s early in the evening of September 21, 1960, Pat Hughes knows that he and his mechanic, Thomas Stacey, are in trouble. It has been a very long day. The North American B-25 Pat is piloting, U.S. registration N9091Z, is low on fuel and the weather is getting worse. To top things off, there is virtually no moon illumination tonight, it is very dark. Flying in Central America in 1960 is dangerous enough as it is. But flying after dark without proper clearance over the airport near the town of Flores, in El Petén department, Guatemala, is downright taboo. Pat is well aware that said “civilian” airfield closes at 1800 and reverts to military control, and it has anti aircraft guns installed.

Pat left neighboring Belize this morning, to deliver a load of cargo to Tapachula, Mexico. After departing Tapachula, Pat picked up a second load of more lethal cargo for delivery to another destination, which required a long over water flight. The second delivery has taken longer than planned and consequently they are running behind schedule. Now, Pat has arrived back over Flores after dark, and he has been unable to establish radio contact with the Guatemalan Army personnel that controls the airfield. This is a very dangerous position to be in. The Central Intelligence Agency -CIA- has been using the Flores airfield as a staging base for flights into Cuba, while they finish construction on the airbase at Retalhuleu. For security, they have installed 20mm Oerlikon anti-aircraft guns at several places along the runway.

Pat circles the airfield for several minutes as he tries unsuccessfully to contact the “tower” at Flores. Finally, guns or not, he is forced to attempt to land because they are getting low on fuel.

91Z successfully executes the approach and makes visual contact with the airfield on final. But suddenly, a gunner with itchy fingers swings his Oerlikon gun toward the converted civilian B-25…

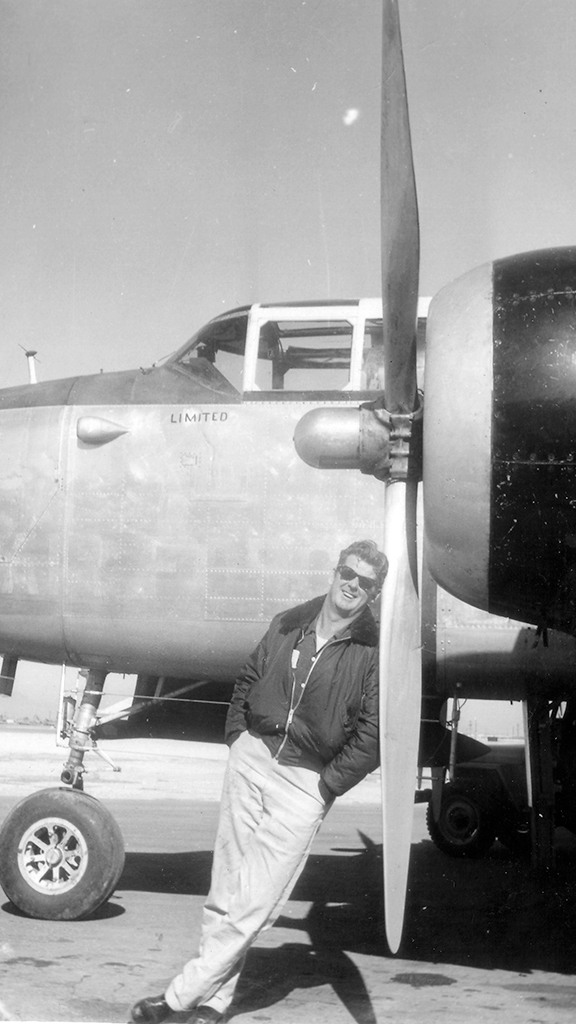

Pat Hughes

Clyde Benton Hughes Jr., “Pat” was a friend of mine. Since the age of seven I have wondered what happened to him and, for several years, I have been actively seeking answers to the crash that killed Pat on that night in September 1960.

Pat had grown up less than a mile from where we lived, in Denham Springs, Louisiana. He was four years older than my father, they were both pilots, friends who hunted and fished together, and shared many adventures.

I had always enjoyed Pat visiting our house, bringing over pictures and telling stories of his travels and adventures. You must be aware that this was a time when we didn’t even own a TV set, and a trip to New Orleans, 80 miles away, was a major expedition. So having a friend that traveled to another part of the continent, seeing strange places and doing exotic things was just unbelievable!

Pat had always been a real free spirit, a quietly rebellious personality totally out of character for our little hometown in Louisiana. He was a military pilot, drove a Harley, was a gymnast, wore his red hair a little long, and his car was a convertible, all pretty wild stuff for 1960. Interestingly, Pat had contacts in the Baton Rouge wing of the Civil Air Patrol. Also, according to all the ladies, he was a marvelous “dancer.”

In his car, Pat kept a flight helmet that he used when flying as a crop duster. One of the few times I rode with Pat in his car, I can remember admiring this flight helmet because it was covered with decals of scantily clad women! I certainly had never seen anything like that around our house. That was pretty racy for a seven year old boy at that time.

While still a student at Louisiana State University, Pat had enlisted in the Army Air Corps on December 4, 1942. By April 1945, he had graduated from flight school, got his wings, and was stationed at Harlingen AAF, Texas, flying air-to-air gunnery training in Consolidated B-24s. Pat was rated as a pilot in command of B-24s, but much to his chagrin, the war ended before he ever had a chance to ship out to overseas. So, he finished up his Army Air Corps career in San Antonio, Texas, in 1947.

Over the years Pat owned at least three different airplanes that I know of. The first was a 1935 WACO YKC-S cabin biplane. He acquired here in January 1960. To show his pride of being from Louisiana, he had a large red Pelican painted on the airplane’s vertical stabilizer.

Due to the obvious shortcomings with the Central America road system, the WACO became Pat’s primary means of transportation down south. The WACO was relatively economical to operate, it could take off from an amazingly short stretch of reasonably flat road or pasture, it was pretty safe as far as airplanes of that time period were concerned, and it was a lot faster than traveling by car, especially in remote areas of Central America.

Pat also owned a twin engine Cessna T-50 (the civilian version of the UC-78), which he bought from Hair Flying Service in Baton Rouge. These Cessna twins could be purchased surplus, for a very modest sum after the war. He had plans to use it for hauling various types of cargo. However, the one he purchased was basically a derelict and rarely if ever flew, and he said the only thing he would get out of it was the pleasure of suing Hair over the purchase.

A lot of these training planes had sat out in the weather for the previous 15 years with little proper maintenance, which often led to rotting in their wooden wing spars, and I suspect that this was what doomed this particular airplane. The last time I remember seeing the T-50, probably sometime in 1962, it was sitting forlornly on Ryan airport, its fabric in tatters, tires flat and wasting away to junk. These are very sad memories for a person who loves classic airplanes.

The last airplane Pat “owned” was the heavy iron, a B-25, USAAF serial number 44-86800, which was one of 4,000 plus B-25J models to be built by North American during the war. It was delivered to the Army Air Force on July 31, 1945. This particular B-25 went through a number of different configurations over the years and it was finally converted to TB-25N at the Birmingham Modification Center in June 1954.

American Compressed Steel Inc. of Cincinnati purchased 44-86800 out of the Air Force storage facility at Davis Mothan Air Force Base in Tucson Arizona, on December 19, 1959. Less than one month later, in January 1960, ORBEC Corporation purchased the plane from American Compressed Steel, and on January 25, 1960 ORBEC had it registered as N9091Z.

According to my sources, Pat and two “partners” comprised ORBEC Corporation. So far, I have been unable to locate any other information on ORBEC, or any partners that Pat may have had. I did however manage to find the lawyer that handled the paperwork for the purchase and registration of 91Z by ORBEC. When I inquired about the details of ORBEC and its principals, he did a great Sgt. Schultz imitation…”I know nothing!” His letter to me indicated very clearly that he wanted nothing to do with my investigation. My gut feeling is that this was not the only work of this nature that he ever performed.

I have a picture of Pat that shows him picking up his new plane in Tucson, in early 1960. He appears to be quite pleased with himself, and quite proud of his new acquisition! Like his WACO, Pat showed his pride of being from Louisiana by having a large Pelican painted on both vertical stabilizers of the B-25.

Normally, Pat was very outgoing and personable; he always had a smile on his face. We had a picture of Pat laid up in a hospital bed, with two broken legs, a big bandage on his throat, and all of his front teeth knocked out, all the result of a crop dusting accident. Even with all those painful injuries he still had his trademark grin on his face. Pat spoke in a high-pitched gravelly voice and had a peculiar tick of his chin as a result of that accident. Pat had suffered damage to his voice box and for the rest of his life he sounded like he was in pain anytime he tried to speak.

Every time Pat came to visit at our house, he would rough house and play with my brother, and me. Pat was well over 6’ tall and a very physically fit person. He would tumble and throw us kids around like little rag dolls. Having Pat around was great fun for two rambunctious boys. However, even as a young boy, I can distinctly remember that when he last visited us, I think in July or August, he was very distracted and troubled. Something very serious was on his mind.

A Mysterious Disappearance

Then, one morning in September 1960, my mom and dad gave us the bad news. Pat had been killed in the crash of his B-25 “near Flores, in Guatemala.” His body was not returned until the following spring, March 1961, that is a month prior to the Bay of Pigs invasion. Even after all these years, I remember as plain as if it were yesterday, attending his funeral. I can even remember all the little boys, myself included, scrambling to pick up the empty brass from his 21-gun salute.

I had never been satisfied with the official version of what happened to Pat. I always thought there was much more to the story than what we were being told. The details of his death were always very sketchy and seemed to change according to whom you talked. One version had him descending too low and hitting the water as he attempted to land at Flores after dark. The other said he had flown into a hill some distance from the airport. But back then, people just assumed that their government would tell them the truth about such important events, we were so naive.

I would find out years later that I was not the only one that was frustrated by the inconsistencies in Pat’s death. His father, Colonel “Bull” Hughes, spent the rest of his life quietly trying to find out what had really happened to his son. But back then, before the freedom of information act, you might as well have been talking to a stone as far as getting any information out of the government was concerned. Pat certainly wasn’t perfect by any stretch, but I always believed that he deserved better than to disappear, under such suspicious circumstances, and never have anyone know what really happened.

Eventually in early 1961, a sealed metal box approximately 12”x 18”x 60” was finally returned to Mr. Hughes. Colonel Hughes never had the box opened, or the remains examined. No positive ID of the remains was ever made. There was never any verification that whatever was in the box was even human! We never knew why Col. Hughes never had the box opened. Perhaps he was told not to go there, by someone in the government.

By 1961, Col. Hughes was getting sick and perhaps he did not have the strength left to fight it anymore. But my mother always said there was no way one of her sons would be laid to rest without a positive ID being completed. As events transpired, the funeral happened so quickly that it would have been virtually impossible for anyone else to raise the issue of examining the remains. Pat arrived at New Orleans Moissant Airport on Aviateca Airlines flight #300 at 6:00 PM on March 9. And he was already buried by 5:00 PM the next day!

I’m not sure exactly what Pat had in mind, when he went down south. But he talked about getting a big airplane and importing fish or lobsters. What kind of lobsters and to where he intended to import them, we were never quite sure! I also have often wondered about his choice of aircraft to do this “cargo” hauling. A different airplane, one more suited to this type work, such as a Beech 18 or a Douglas C-47 would seem to have made a lot more sense than a B-25.

The B-25, by its nature, was not a very efficient cargo hauler. It was noisy, burned a lot of fuel, and used a lot of runway to get airborne. So in order to “pay the bills” you would need to be hauling cargo that was a lot more profitable, than seafood or chicle.

Pat first traveled down to Central America in 1959 to seek his fortune. He was a nice guy, but he always seemed to worry more about “adventure” than earning a steady paycheck! This particular characteristic was a constant irritation to his friends because Pat never seemed to have any money. He would disappear for a time, to who knows where, then he would show up, ask to sleep on the couch and be bumming food from the fridge. But he was such a likeable guy that his friends, my parents included, seemed to forgive his faults.

My father offered many times to help Pat get a more stable job as a corporate or airline pilot. Pat’s skills as a pilot were quite good enough to have made him very successful at these kinds of jobs. But Pat was just not wired that way. He obviously had a “wanderlust” that could not be satisfied by any old common flying job.

We received our first letter from Pat posted in January of 1960, from Mérida, Mexico. By March of 1960, he had turned up in both Nicaragua and Guatemala. He had a few scrapes with local authorities in different countries, something about arriving by airplane unannounced. The various governments were understandably, a little nervous about gringos just showing up unannounced in airplanes, especially bombers. Pat was forced to use his gift of gab more than once to extricate himself from uncomfortable situations.

Most of the time, this talent served him well. As an example he related a story about “two countries down here” sending out airplanes to look for him, when they feared he had crashed. They wanted Pat to pay for the fuel for their airplanes they had used while searching for him. He proceeded to explain to them about our Civil Air Patrol, and the benefits of having well trained personnel and systematic search procedures. “Neither country offered me an honorary commission, but then again, they haven’t been reimbursed either!”

Sometime that summer, Pat managed to get the WACO seized. Talk about serious red tape problems! He was forced to fly back to Managua by airline. He apparently was successful in getting the WACO out of seizure, possibly with a little help from his friends, because the WACO shows up again, in a picture, in Belize, in the “fall of 60”. This I suspect is the last picture ever taken of that biplane.

In June, he sent a letter to my dad authorizing him to sell his Cessna T-50 airplane for whatever he could get for it. This letter was written from the Grand Hotel International, Tapachula, which is a small city located in extreme southwest Mexico, and only about 50 miles from the secret bases the CIA had started constructing, only a month earlier, near the town of Retalhuleu, in Guatemala. During the summer of 1960, Pat was also operating frequently out of Nicaragua and Belize.

I do not have any evidence to indicate what Pat’s primary motivation for getting involved in Central America was. To my knowledge he never spoke or wrote about it one way or the other. However I feel it is most likely that he became involved primarily for the rush caused by the adventure, and a good paycheck certainly did not hurt! Flying “cargo” into places such as Cuba seemed to be just the ticket to making a lot of money quickly, if you survived. One pilot, who claimed to have made several flights over Cuba, supposedly told his friend that he made $2000 per flight. This was quite a lot of money for 1960, when a typical pilot could expect to make $450 per month at a good job here in the U.S.

In one of his letters, written in the summer of 1960, Pat makes a very revealing statement; he said, “The U.S. State Department, Arms and Munitions Division has put out a new and stricter policy that has just about put us out of business down here. Keep MUM on this. Too many people with plain clothes & fancy badges are asking where & what about me as it is!”

Declassified documents reveal that in March 1960, the CIA had drafted a top-secret policy paper, “A program of Covert Action against the Castro Regime”. In this policy paper it was acknowledged that there already existed under CIA control “a limited air capability for resupply and for the infiltration and exfiltration of personnel”. This capability could be “rather easily” expanded if and when the situation required it. It was planned to parallel this existing capability with a “small air supply capability under deep cover as a commercial operation based in another country.” (Belize perhaps?)

This operation was to be up and running within two months. The planned full capability would take an estimated six months, or by September 1960. At this same meeting it was discussed as to the desirability of removing the top three leaders, Fidel Castro, his brother Raúl Castro and Ernesto “Ché” Guevara, simultaneously. It seems obvious, based on Pat’s letter, he had become involved in this “air supply” part of the CIA operation.

At the conclusion of the late summer trip, when Pat had seemed so distracted, we were taking Pat to the airport, and he startled my dad with a rather chilling story. Pat related to my father, that “they” had offered him $10,000 to assassinate Castro. He never said who “they” were. We just always assumed it was one of the anti-Castro groups. Hell, at that time I don’t think we had ever even heard of the CIA! Pat said he had declined the offer because it would have resulted in innocents being killed. Pat obviously had a number of character flaws, but the killing of innocent civilians was not one of them.

The timing of this conversation is significant, because documents released by the CIA reveal that in July 1960, CIA headquarters sent a cable to the Havana station chief, regarding “possible removal of top three leaders”. It also addressed arranging an accident for Raúl Castro, and offering $10,000 payment after successful completion of same. I don’t think that Pat’s conversation with my dad and the timing of this cable was just a coincidence.

In May 1960, the CIA had instructed the Station Chief in Guatemala City to start building a secret airbase near Retalhuleu in Guatemala. This airfield was called JMMadd by the CIA, and Rayo Base by the exiled Cuban pilots. It was located very close to Retalhuleu City in western Guatemala. The airbase was placed there in order to support the primary training base for the Cuban Brigade 2506. This base, called JMTrax was located on a coffee plantation known as La Helvetia, up in the mountains between the city of Quetzaltenango and Retalhuleu.

Both JMMadd and JMTrax were supported by the daily airlifting of supplies in from Happy Valley or JMTide, the code name for the CIA base in Puerto Cabezas, Nicaragua. Interestingly, I know Pat had visited Puerto Cabezas as early as March 1960. The CIA had used Puerto Cabezas during its earlier adventures in Guatemala in 1954, and it was still crawling with CIA types. Both JMMadd and JMTrax were completed by September 1960.

Taking personnel into various remote locations for site surveys, and similar other missions were exactly the type of flying that the WACO would have been perfect for. The WACO could easily takeoff and land on as little as 1000’ of straight road or cleared field. We know that Pat installed a fresh engine on the WACO while he was down there. He talked in a letter about how it would “leap” off the ground with the propeller adjusted properly as per instructions from my dad. It was not particularly fast, 110 mph cruise speed, but it could haul a good load and do it out of very small places.

The WACO could also have been used to take agents into Cuba or to pickup high value personnel from Cuba. It would have required refueling in the island, but its ability to operate out of very small remote locations would have been a great asset. Pat certainly had the skills necessary to operate the WACO near its limits! As a result of experience acquired the hard way during his crop dusting days, Pat was a pretty darn good pilot, and would have thrived in this environment.

In early September, Pat made a trip back home to Louisiana, to pick up his personal belongings and his car. While he was here in the U.S., he made a “quick” trip to Houston, and Tucson. The city of Houston surfaces often when doing research on any of the various “spook” activities, and of course Tucson was the epicenter for a plethora of surplus military airplane parts. Also, another source indicated that Pat had plans to pick up another large aircraft. After completing the trip out west, Pat drove his car all the way back down to Belize. He obviously had intentions to stay down south for quite a long while. He arrived back in Belize on the evening of September 17, 1960. It seems that by then, Pat had decided to move down south permanently.

While technically not a cargo plane, the B-25 could have done an excellent job of air dropping specialized supplies. Pat’s aircraft, N9091Z was one of over 900 B-25J’s that went thru the Inspect and Repair As Necessary (IRAN) program conducted by Hayes Aircraft between 1952 and 1954. 91Z came out of this program as one of only 60 solid nose TB-25N’s. On the TB-25 conversions, all the guns, armor plate, and gun turrets were removed. These modifications removed approximately 1,250 pounds in weight and eliminated the considerable aerodynamic drag of the turrets and gun blisters.

91Z still had an operable bomb bay, and these TB-25 modifications would have made the airplane ideal for air dropping high value cargo. The TB-25, being capable of over 300 mph, was a lot faster than the C-46 or C-54, and it had plenty of range for the job. Loaded with a standard fuel load, you would have a useful range of approximately 1,500 miles, enough to easily fly from Belize or Flores to the Cienfuegos / Trinidad area and return, with a good reserve.

After Pat´s funeral in March 1961, Colonel Hughes asked a local pilot, named John Waldron, to travel down to Tapachula to look into Pat’s accident and to recover his WACO. John was told to contact a person in Tapachula, named Luis López. Luis told John that Pat had crashed while hauling “cooling pipes” from Tapachula to a refrigeration plant being built in Belize. This story fits in very conveniently with the CIA’s “cargo operation located in another country” cover story.

However, this version of Pat’s death just never did ring true…Transporting any cargo by airplane is expensive, and normally, for economic reasons, cargo being hauled by aircraft needs to posses one or more of three specific characteristics: The cargo needs to be dense, it needs to be of high value, and it usually is time sensitive as to its delivery. Pipe meets none of these criteria. Also, the bomb bay on a B-25 can only accommodate items that are at most 8 feet long. This restriction would severely limit the efficiency of the B-25 as a pipe hauler. So, it just does not make sense that they would have been hauling pipes by B-25.

John was never allowed to go to the scene of the crash in Guatemala. So he never saw any aircraft wreckage, (with bullet holes?) nor did he ever talk to an actual witness to the crash or recovery of the remains, other than the mysterious Luis López. During his entire time in Tapachula, Luis, who also acted as an interpreter, escorted John everywhere he went. I have been unable to determine who or what Luis López actually was. Was he just a friend of Pat? Or was he a local official? Or did he work for the CIA and his job was to give the cover story to any nosey officials or relatives that might come snooping around? Interestingly, while examining declassified CIA documents, I found an armaments specialist named Luis Gonzales López; listed on the roster of personnel assigned to the Bay of Pigs B-26 support crew! Another coincidence?

In the end, John was not able to recover Pat’s WACO because it had been sitting out in the elements for more than six months and he was unable to get the engine to crank. The magnetos had gone bad and he was unable to secure replacements or fix the problem. So unfortunately, N15236 sat out in the tropical Mexican weather and quite quickly wasted away into junk.

You must realize that Flores in 1960 has been described as like the “wild wild West.” It was so isolated that it was quite easy for the CIA to set up flight operations there, pending the completion of the secret base at Retalhuleu. My sources also indicated that Flores was not the only base used for supply flights into Cuba. However, Flores was one of the most valuable because it had a hard surface runway, long enough for larger aircraft like a B-25. Flores was also within easy range of central Cuba for the aircraft being operated on the supply flights. It also makes perfect sense that the Guatemalans (or the CIA) would install some means of protecting their most important stage airfield.

A Sound Theory

Sources I tapped for this investigation included the CIA, FBI, FAA, OSD, DIA, DOD, State Department, National Archives, as well as many private organizations and private individuals. Numerous FOIA requests and investigations of every conceivable source of information on the crash provided very little in the way of documents. I found this to be both frustrating and suspicious, considering that by Pat´s own admission, just about every U.S. agency down there had an ongoing investigation on him!

What documents I have NOT been able to locate are very revealing. I was unable to find any memos, reports of investigation, accident reports, and significantly, no pictures of the crash. At least three highly skilled, experienced individuals from the U.S. Embassy in Guatemala, the Consul, the Air Attaché and the Assistant Air Attaché, all went to the crash site to conduct an on the spot investigation. That seems like a lot of heavy brass just to investigate the crash of a common civilian aircraft. During the investigation, pictures WERE taken of the crash, but so far I have been unable to locate them.

Those few documents that I WAS able to uncover, turned up a significant amount of interesting details. I have “The Report on the Death of an American Citizen” for two individuals, Clyde Benton Hughes Jr. and Thomas Carlysle Stacey Jr., along with a telegram from the U.S. Ambassador reporting the crash of a civilian B-25 near Flores, El Petén. In addition, I also discovered a letter during my investigation, from Assistant Secretary for Congressional Affairs, Mr.William B. Macomber, to Congressman Joe Madison Kilgore, of Texas, saying that Pat´s crash site was “several” miles north west of the Flores airfield. Also, the letter stated that Thomas Stacey was the only other American citizen killed in the crash, not two others as was first reported in the newspapers.

The letter is doubly interesting because it was written in response to an inquiry from a constituent of Kilgore’s named Floyd Park. Mr. Park is now deceased but a quick search of his name in the CIA files reveals a lot of interesting things. Mr. Park was a pilot, he led a very interesting life on the fringes and he traveled extensively all over South and Central America. He worked part time for the U.S. government and did “a lot of good work and some very, very bad.”

Mr. Park had called congressman Kilgore, asking him to look into reports that Pat´s airplane had been shot down by the Guatemalan Air Force! This letter to Congressman Kilgore is very carefully worded so as to deny the allegations that Pat was “shot down or otherwise forced down by the actions of other aircraft”. However, it conveniently ignores the possibility that Pat´s crash could have been caused by other outside influences, such as ground fire.

So what actually happened to my friend? I managed to locate, after much looking and more than a little bit of luck, a pilot who was friends with both Pat and Floyd Park, down in Belize. His name is Max Leslie. Mr. Leslie and Park were both cut from the same cloth. He also had some very interesting adventures during more than thirty years down south. I have had several conversations with Mr. Leslie, who at the time was 88 years old, and still sharp as a tack. He was a friend, a mentor and an advisor to Pat. He helped him load up his cargo that morning in Belize and then started a search for him when he turned up overdue that evening.

According to Max, that morning Pat departed from Belize with a load of cargo, and headed for Tapachula. Pat was seen departing the hotel that morning after removing a large sum of money from the hotel safe. After delivering his cargo to Tapachula, Pat then took off for a second delivery flight. Airplanes can’t make money sitting on the ground, so Pat had arranged for another delivery of a more lethal nature that day.

I believe he left Tapachula and flew to another site, probably Flores where he picked up a load of munitions to be delivered to anti-Castro guerrillas near Trinidad in central Cuba.

During the early months of 1960, an uprising by former supporters who had become disillusioned with Castro had started to flare up in the Escambray Mountains, centered between the towns of Cienfuegos and Trinidad. The Escambray Mountains are on the southern coast of Cuba in about the middle of the island.

Arrangements with the CIA had been made to airdrop rifles, ammunition, and supplies to these rebel forces by parachute. The drop had been scheduled for September 1960. The specific day remains a mystery, but available evidence indicates it had been arranged for sometime around 21 September.

Before this supply drop could be carried out, Castro’s militia found and attacked the rebel group. During one of these first encounters, sometime around September 17 (sources disagree on the exact date), a Lt. Obdulio Morales Torres was shot and killed. As a result of the fighting, the militia captured the original drop zone, and the rest of the guerrillas were forced to break up into small groups and attempt to evade and escape. After evading the militia for “several days”, the rebel group leaders tried to make radio contact with the CIA, to tell them that the militia had captured the original drop zone, to reschedule the airdrop for a later date and to utilize a different drop zone. Unfortunately, the rebels were unable to make contact with the CIA or the aircraft that was scheduled to make the drop.

I believe Pat was the pilot that was attempting to make this supply drop, “several” days after that first contact, of September 17.

Since the navigation equipment on board the B-25 was quite primitive compared to modern day aircraft, I think they would have planned the parachute drop to take place in the afternoon. This timing would eliminate the need for lighting the drop zone, and allow the flight crew a much better opportunity to find the zone and make the drop on the first pass successfully.

The Cuban air force had at that time, approximately 14 operational combat aircraft in the fighter or attack categories. These aircraft were believed to be stationed at the three primary Cuban military airfields, Ciudad Libertad, (1 T-33A), Santiago de Cuba (1 B-26C), and their primary airbase at San Antonio de los Baños (5 B-26C’s, 4 T-33A’s, 3 Hawker Sea Fury.)

Radar coverage in the Trinidad area was non-existent at that time, so the likelihood of the Cubans successfully intercepting a fast target like the B-25 at low altitude would be very slim. A low altitude airdrop taking place over 150 miles from the primary Cuban military airfield would have had a very good chance of success. The only real threat to such a mission would be from ground fire.

Pat would have flown directly over an occupied drop zone at low altitude, straight and level, while it was still light enough to be seen by the troops on the ground, When Pat flew into this hornets’ nest and the tracers started flying, the situation would have turned pear shaped very quickly. Undoubtedly this part of the flight turned out to be more than a little bit sporty! Pat was a good pilot, and the load hit right on the drop zone, and the Castro militia captured all the supplies!

Something unknown to me at this time, possibly damage from ground fire or unfavorable winds, slowed his return flight, we will probably never know exactly which. But since he was not on a flight plan, which would have allowed him to land at Belize City after dark, Pat was forced to make an unplanned return to Flores that evening. He arrived back in the vicinity of Flores at approximately 1900 local, well after dark, low on fuel, and in deteriorating weather. After circling for several minutes and being unable to contact any personnel on the ground, Pat was forced by circumstances to initiate an approach into Flores. Since no flights into Flores that evening had been expected, and Pat had been unable to contact the forces that controlled the airfield, it was assumed, on the ground, that the approaching aircraft must be unfriendly. According to Max, while on short final, Pat was fired on, and hit, by one or more of the 20mm antiaircraft guns placed there by the CIA.

The information provided to Max was so detailed that he even knew what injuries Pat had suffered. According to the source, Pat had been hit in the head and was either killed outright or was injured so severely that the mechanic, Thomas Stacey, was actually trying to control the aircraft when it crashed. According to our conversations, Max got his information directly from a source that had access to highly placed officials in the Guatemalan government.

Paradoxically, Pat had asked my dad in an earlier letter, to “keep an eye out for some good long range navigation gear and some good communication radios; some that you don’t have to buzz the tower to be heard.” In this particular case, not being able to communicate with the guys in charge on the ground cost Pat and Stacey their lives.

I was struck by the unusual type of weapon used to shoot Pat down. The 20mm Oerlikon was very common on U.S. ships, but was quite rare compared to the proliferation of .50 caliber guns available at that time. But an examination of CIA documents revealed that, as of 1954 there were at least 26 – 20mm Oerlikon guns and 2000 rounds of ammunition either in inventory or being shipped to Guatemala.

Max said he and Park kicked up such a fuss about Pat’s shoot down that finally a couple of “goons” from the Embassy showed up and told them in no uncertain terms to drop the whole matter.

Obviously, the CIA needed to keep this shoot down very quiet in order to not risk exposing their ongoing “cargo” operations. How do you explain the shoot down and death of two American citizens, flying a civilian aircraft, into a civilian airport controlled by the CIA? Well, the answer is obviously, you cannot, so you must make it go away. Someone would have had to fly Pat´s WACO into Tapachula in order to get it two countries away from Pat´s base of operations in Belize. Then, when Waldron came down to look into the crash, López was there to feed him the official story, and help him get on his way back home to the U.S. as soon as possible!

So for more than 60 years, the real circumstances of my friends’ death have been very successfully hidden away. In conversations with several pilots who flew in and out of Flores on a regular basis, none had any knowledge of a B-25 crash ever even taking place there. In addition, the Guatemalan Civil Aeronautics Directorate has no record of the crash of 91Z.

The Final Moments…

After circling for several minutes in the vicinity, Pat is unable to contact anyone on the ground to tell them they are friendly. They are low on fuel, and the weather is getting worse, so Pat is forced to initiate an approach.

About 1/2 mile out from the airport on the final approach, the sky lights up with 20mm cannon fire. At 300 feet AGL with gear and flaps down and approximately 110 mph, 91Z is like a sitting duck. The gunners on the ground can hardly miss. Pat’s supply of luck has finally run out. To avoid the tracers arching up at him, Pat instinctively turns the B-25 hard to the left. But the projectiles come crashing through the cockpit and left side of the fuselage. The left engine, as well as the fuel and oil tanks in the left wing and nacelle have been hit several times, 91Z is leaking hydraulic fluid, engine oil, and high-octane avgas, the pilot, my friend Pat Hughes has been injured, and 91Z is doomed.

91Z continues its left hand turn but just does not have enough altitude to make it back to the airport. They start clipping into some unseen treetops with a sickening sound of tearing metal and then mercifully it is over very quickly. N9091Z’s final resting place is 3.2 miles west north west of Flores airfield.

The destruction of 91Z is so complete there is very little left to recover. Both Hughes and Stacey are killed instantly. Even the part of the fuselage bearing the registration number is damaged so severely that the people who eventually find the wreckage report the N number incorrectly. They mistakenly report to the U.S. embassy the crash of a B-25, with no survivors, registered as “71606.”

No matter how “good” a pilot is, sometimes circumstances can gang up, and unless lady luck smiles on you, you are toast! Unfortunately this is just what happened to my friend.