Up to this date, we have five decades worth of material written about the nine-month guerrilla campaign led by Ernesto “Che” Guevara in Bolivia. Unfortunately, an overwhelming amount of such literature either mystifies Guevara or is, at best, biased against the Bolivian armed forces. In fact, relatively little has been written about that “other side” of the campaign, and we still lack an “official history” of the events in which the three branches of the Bolivian armed forces, as well as the national police, participated. The best accounts available from the side of the Bolivian military were written by Gen. (R) Gary Prado Salmón, a direct participant in the capture of Guevara. The literature about the participation of the Air Force in the campaign is even scarcer. In this article I intend to cover –albeit modestly- this aspect of the campaign.

The Historical Context of the Insurgency

1966 marked the seventh anniversary of the overthrowing of Cuban ruler Fulgencio Batista. A lot had happened since 1959: Fidel Castro had consolidated his position as the new ruler of the island, and had managed to remain in power despite a failed invasion and a crisis that brought the world to the brink of nuclear war. However, by 1966 Castro had also failed to “export the revolution” to other Latin American countries. Despite this failure, the Cold War still raged elsewhere in the world, and Castro remained firmly under the influence of the Soviet Union. The island continued to be a base from which to launch communist expeditions and a place of shelter and training for guerrillas and terrorists alike.1

Following the principle that the use of violence was acceptable to bring about a communist regime and the strategy of “foquismo” Castro and his cadre decided that it was time to open a new battle-front for communism.

Located in the center of South America, Bolivia shares its sparsely populated borders with five other countries; and in 1966 it presented some conditions which both foreign and local communist ideologues believed ideal for launching a guerrilla campaign and establishing a base camp to prepare other expeditions.

At the time Bolivia was governed by Gen. (Air Force) René Barrientos Ortuño, who initially reached power as part of a military junta but was elected president in 1966. A strong populist figure, Barrientos enjoyed broad support from the peasantry and the middle class, while his strong anti-communist stance garnered him support from neighboring countries and the USA.

His opposition, traditional parties such as the Falange Socialista Boliviana (FSB)2 and the Bolivian Communist Party (PCB) although strong in some areas of the country3, were in disarray and unable to pose any real threat. The Movimiento Nacionalista Revolucionario (MNR), a party to which Barrientos had once sworn loyalty and eventually abandoned, offered tacit support to the policies of the new government.

The military, once defeated by the armed populace in 1952, finally began to regain its strength by the early 1960’s. Although rejuvenated by a new type of officers, the armed forces remained numerically small and equipped with obsolete material. Its training and operational doctrine remained focused on conventional warfare and internal security.

The Army continued to use material left over from the Chaco War, the basic infantry rifle was the 7.65mm Mauser and support arms included Vickers and Colt machine-guns, 81mm mortars and a few 75mm artillery pieces. American made equipment, which began arriving in 1958 consisted mainly of M-1 and M-2 rifles and carbines, Browning machine-guns, 60mm mortars, 57mm recoilless rifles and some WWII-vintage 3.5” rocket launchers. The American material equipped a few units, especially those dedicated to internal security roles.

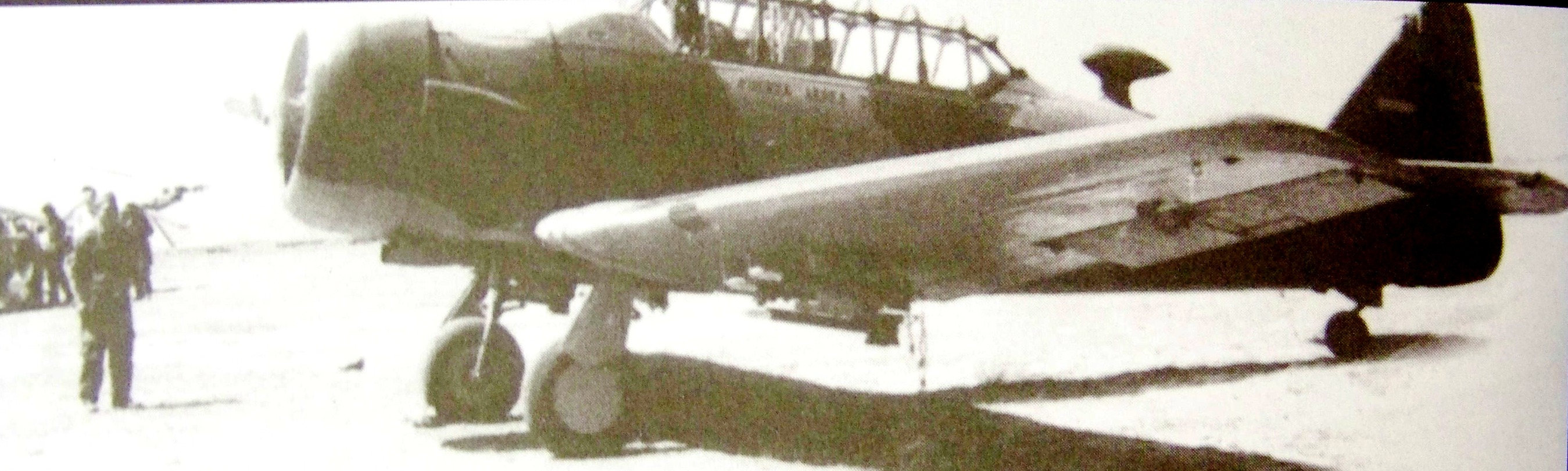

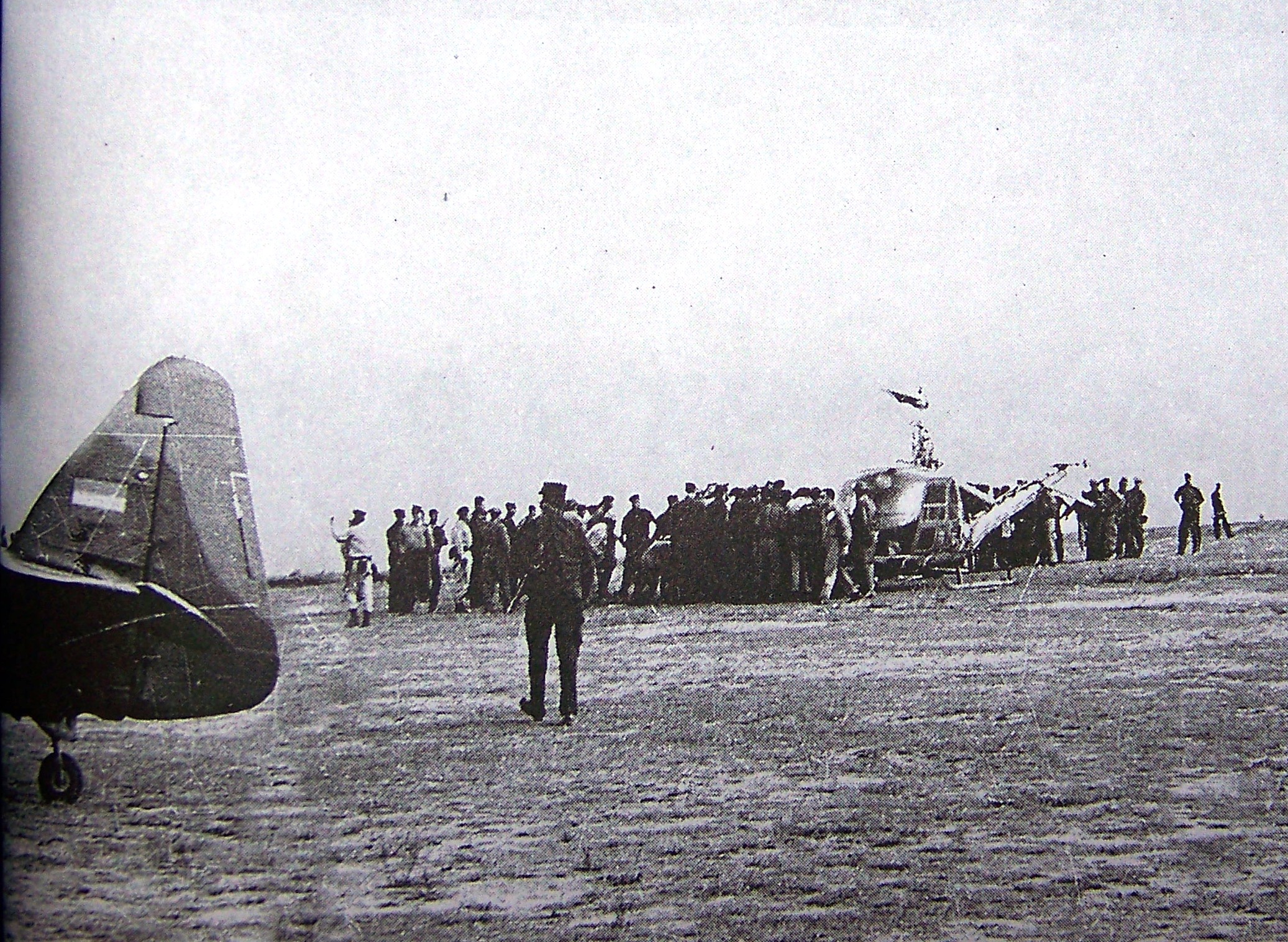

The Bolivian Air Force, a separate branch of the military since 1957, had also moved towards American doctrine, although much earlier than the Army. By 1966 it was largely equipped with American-made equipment; the bulk of its combat force consisted of Cavalier F-51D and North American AT-6 airplanes. Training was carried out on Brazilian-built PT-19s, and North American T-28s. Transports included Douglas C-47, DC-3, C-54 and Curtiss C-46 aircraft. Utility planes included single examples of the Cessna 180, 195 and the Beechcraft AT-11, as well more numerous stocks of the Cessna 185 (U-17A/B). Finally, the helicopter had been introduced to the Bolivian military in 1966 in the form of one Hiller UH-12L4 and two H-23s.

The Air Force order of battle4 consisted of Air Base Nº 1 in El Alto from where a fighter group (GAC-31) with 4 squadrons operated, as well as one anti-aircraft “squadron”, and one transport group with 2 squadrons. Air Base Nº 2 in Cochabamba had one mixed group (GAMX) formed of 4 squadrons (until 1967 the group was known as Aerial Detachment N.o1). Air Base Nº 3 in Santa Cruz housed the Military Aviation College (2 squadrons), Air Base Nº4 in Trinidad had no organic squadrons and Air Base Nº5 in Tarija had the Aerial Detachment No. 2. On its part, the Aerial Detachment No.3 operated briefly in Caranavi. Still functional were Grupo Aéreo No. 1 in Villamontes and Grupo Aéreo No. 2 in Cuevo. Lastly, operating in Riberalta was the Grupo Aéreo de Cobertura.

Due to attrition and lack of spares, the majority of aircraft on hand were not airworthy. The combat fleet was specially diminished as most of the operational F-51Ds were in the U.S. undergoing modernization work to Cavalier standards for most of the campaign.

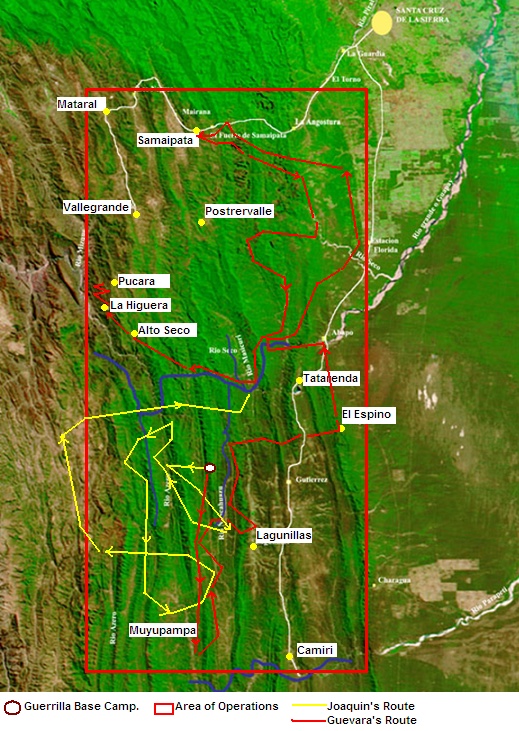

Area of Operations

The Ñancahuazú campaign took place in an area of approximately 40,000 Km² (4 percent of the Bolivian territory) in Southeast Bolivia. The theater occupied portions of the Chuquisaca and Santa Cruz departments, although other parts of the country had been studied as possible zones of operation5; Guevara chose this location purportedly for the agrarian nature of its economy and theproximity to some oil fields. The area itself forms a rectangle with its North boundaries delimited by the Cochabamba-Santa Cruz road, to the West by the Mizque River, to the East by the Camiri-Santa Cruz railway and to the South by the Parapetí River. The area is dotted with small towns, the largest of which is Vallegrande with a population 7,800 at the time. Most towns are located in mesothermic valleys, and the area is generally mountainous and warm, vegetation is low and water scarce. As a historical digression we should mention that this terrain is very similar to what the Paraguayans encountered in the last stretch of the Chaco War.

The means available to sustain the guerrilla include two major rivers and their small tributaries crisscrossing the area – barely the only sources of clean water. The peasants maintain small plots of corn, rice, sugar cane, yucca and some fruits. Game is available, and most farmers keep small quantities of cattle. Nine main roads as well as one railway connect the towns with each other and the larger cities of Cochabamba and Santa Cruz. The only permanent airfield in the area is located in Camiri, although some stretches of land or dry riverbed were usable for emergency landings, a landing strip was built on the town of Vallegrande during the campaign, and used extensively.

Preparation on the side of the guerrilla unit consisted on the accumulation of ammunition, arms, food and clothing. Some items were acquired in excess with hopes of enlisting local men. The group also acquired a 1,227-hectare property some 25km from the town of Lagunillas, the place was simply called Casa de Calamina. The isolated property was planned to be used as a base camp from where to launch reconnaissance missions. The guerrilla group consisted of 30 Bolivians, 17 Cubans, and 6 other nationalities. With the exception of journalist Regis Debray (nom de guerre: Danton) all were combatants, although with varying degrees of efficiency and expertise. For all intents and purposes the local troops (units from the 4th and 8th Army divisions) were not prepared to face the guerrilla force.

1st Phase of Operations6

Guevara begins his campaign diary on November 7, 1966 the day he arrived in the Casa de Calamina property, his account of the next four months details the many reconnaissance missions undertaken by his group, the arrival of new personnel and the preparations on the 3 guerrilla camps built.

Despite previous encounters with the police7, coincidence brought the first news about the presence of the armed band to the military command of the 4th division. On March 9th, 1967 Capt. Augusto Silva, who was coming back from a civic action mission hitched a ride with a YPFB8 vehicle on the road to Camiri. On route to the city (a 100km distance) the driver and aide informed Silva that on the 5th and 6th of the month they had encountered six suspicious “bearded and foreign-looking” men at the Tatarenda pumping station. The men described were armed, wore olive drab clothes, had purchased food and had plenty of money.

As soon as he arrived in Camiri, Silva informed his commanding officer of the news; the following day both meet with the local YPFB superintendent in order to coordinate a search. And so, the first aerial sortie of the campaign, a reconnaissance flight, was flown on a YPFB utility plane. On the morning of the 11th, as the plane returned from Santa Cruz to Camiri, Capt. Silva and another officer were able to see a group of four men on the shores of the Rio Grande who, upon sighting the airplane, ran for cover in the brush. This became sufficient reason to organize a search on foot. The Silva patrol, composed of 6 soldiers and the officer, reached Tatarenda by road on the 12th and continued on a West-bound direction towards the Ñancahuazú River; poorly supplied and armed only with 5 submachine guns and a pistol, the patrol reached the Casa the Calamina on the 17 of March.

The guerrilla force of 47 strong at the moment, was split in three groups; the first group had not returned from its reconnaissance trip to the Northeast. The second group, encamped some 2km North from Casa de Calamina, did not notice the military presence. The third and smallest group, based at the property, withdrew from the area as soon as the patrol arrived, although they managed to wound one of the soldiers. Capt. Silva occupied the house and set up to guard the place. Unbeknownst to him, two guerrilla deserters had been captured and interrogated on the 12th, and after hearing their confession, the military command of the 4th division began to organize its response.

After this first encounter, operations escalated to include the deployment of two larger patrols (about 60-strong each) in reconnaissance missions up the Ñancahuazú river; one of the groups, led by Major Hermán Plata reached Casa de Calamina on the 22nd, joined the Silva Patrol and continued the operation; on the 23rd of March, the group was divided in 3 segments. As the vanguard prepared to cross the Ñancahuazú river, they were ambushed by one of the guerrilla groups. The ambush yielded a terrible result, as six troops and a civilian guide were killed, 5 were wounded and 18 captured.

The rest of the troops withdrew to Pincal and awaited for orders; the prisoners were released the next day. On the 24th two AT-6s flying from Camiri bombed the suspected guerrilla positions up river in the first attack mission of the campaign. That same day a paratrooper Company (81 men) from the Centro de Instrucción de Tropas Especiales (CITE) in Cochabamba is flown to Camiri; on the 25th a mixed Company of soldiers is flown in from Santa Cruz.

On the 26th, president Barrientos arrives in Camiri and flies on an H-23 to the Casa de Calamina. After a brief stay just a few miles from Guevara himself, Barrientos returns to Camiri and gives a press conference; it is now official that a guerrilla force is acting in Southeast Bolivia. Aerial reconnaissance missions continue on the following days, with one aerial supply sortie recorded on the 27th and another bombing mission9 on the 29th.

On April 1st, the Army command makes a decision on how to confront the guerrillas, and orders the 4 companies available (A, B, C, D) to set bases on Yuqui, Pincal, laguna Pirirenda, and Lagunillas respectively. Each company begins its patrol operations on the 3rd; they do not encounter the guerrillas until April 10 when Company A is ambushed near the junction of the Iripití and Ñancahuazú rivers. This is the deadliest combat of the campaign for the Bolivian forces as 11 troops and officers are killed, while 14 are wounded and 23 are made prisoners. The guerrilla casualties include one prisoner and one dead10. The military prisoners are released the following day.

The consequences of this ambush are deeply felt by the Bolivians; it is clear that the troops available are not sufficient or trained for this type of actions, that aerial support cannot be used efficiently, as it is impossible to accurately target enemy positions, and that the opposing forces are experienced and at the moment, well-supplied.

The military command begins to reformulate its strategy, and slowly reinforces its troops: 375 more soldiers arrive from other parts of the country including the Bolivar artillery regiment from Viacha, theNCO school in Cochabamba, the Centro de Operaciones de Selva (CIOS) from Riberalta and the Sucre infantry regiment, a welcomed addition to the 200-odd force that existed in the area.

While the army regroups and re-adjusts, the air force continues its reconnaissance missions using the half-dozen utility planes deployed to the area. It also performs some strafing sorties; Guevara notes in his diary that on April 20th a flight of 3 AT-6s attacked his position and wounded one of his men, Ricardo. Guevara also notes that on the following days his movements were hindered by the constant air patrols. The patrols continue with more strafing close to the guerrilla positions on the 24th.

The guerrillas also use the time to regroup and reorganize, hide some captured equipment and gather supplies. But they have more pressing problems, Guevara notes that their presence has been detected too soon, and that they are dragging an anchor which must be disposed of: journalists Debray and Roth, and local communist leader Bustos. In a “blunder” that probably caused the annihilation of half his troops, Guevara opts to divide his forces and travel towards Muyupampa in order to leave the journalists there, the other half of the group is ordered to stay back. No orders are given in regards to safety, meeting points or dates. The guerrilla force splits on the 16th, never to see each other again.

One of the measures taken by the military during this time of re-alignment is the re-activation of the Manchego infantry regiment in Santa Cruz. With 650 new recruits, the regiment begins training on mid-April; among the instructors are sixteen American Special Forces officers and NCO’s.

With this reserve force in training, the army decides to use the troops present in-theater to surround the Ñancahuazú area, thus encircling the guerrilla forces there. The maneuver is accomplished on the 17th. However, having left on the 16th, the guerrillas are able to escape the encirclement. Noticing this event, the military orders two companies to march South to Muyupampa; the journalists are captured by a group of this force on the 20th. On the same day one air force sortie strafes and attacks the guerrilla positions with rockets, Pacho notes in his diary that no one was wounded.

Realizing that they are very close to one of the guerrilla groups, the Bolivians track them towards hacienda Coripote were a brief skirmish takes place; the guerrillas now in full retreat, continue towards the El Mesón canyon where they prepare an ambush and encounter the military on the 25th of April. Casualties of this encounter with the CIOS Company include a civilian guide and one policeman (and his German Shepherd dog) one of the guerrillas -Rolando- is also killed. The troops withdraw to re-group; on the evening of the 25th a helicopter surveys the area and then calls for air support, and an AT-6 strafes the suspected guerrilla positions.

On the 26th, a guerrilla deserter, Loro, far from the combat zone while on route to Taperillas shoots and kills a Bolivian NCO and a soldier. Troops are diverted to the area, believing this is the work of another guerrilla group.

The enemy now begins its return to their main base camp on the banks of the Ñancahuazú River, they did not encounter resistance on the way, as the bulk of the military force is deployed elsewhere and the CIOS company has lost track of them. The guerrillas arrive in their 2nd camp on the 8th of May, where they are met by a patrol led by 1st Lieutenant Henry Laredo, who is killed with two soldiers, and 19 others are captured. One soldier manages to escape and informs his commanding officers; while two companies begin marching towards the encampment, the air force proceeds to bomb the location only a few hours after the prisoners are released. They continue bombing the area over the next two days. The flight of three AT-6s also strafed the area on the 14th, 15th, 16th and 24th, albeit ineffectively; the army patrols march parallel to the guerrilla line of movement without encountering them.

The guerrillas now move eastward, while the military prepares a ground counter-attack that arrives days after the enemy has left the location. After many days of searching, an air force utility plane spots the guerrillas on the premises of the Pirirenda ranch. The guerrillas enter the brush again and are not found until the 28th of May, when they enter the town of Carahuatarenda and capture two vehicles, which they use to move East towards the Yacuiba-Santa Cruz railway. The army now deploys two mobile companies from RI24 Mendez Arcos and RI1 Colorados, which reach El Espino on May 30th, RI1 continues its search Eastward while RI24 goes Northward, parallel to the rail line. One patrol from this regiment is ambushed while detached from the main group, an officer and a soldier are killed. The next day, one of the trucks of the RI11 Boquerón company, which has joined the persecution and travels the Muchiri road, is struck by a grenade; killing a civilian guide and wounding five others.

2nd Phase of Operations

After three months of operations, the balance clearly stands in favor of the guerrilla force, the military casualties have reached 24 killed and 21 wounded in addition to 4 civilian and one police casualty. The handful of guerrilla deaths was unknown at the time, thus compounding the military frustration. As the situation worsened, radical actions were taken; the 4th division command was replaced in full, and a new plan of action code-named “Cinthya” entered in place. On the “home front” police and military repression in the mines11 and cities increased.

As part of plan “Cinthya”, the order of battle was reformulated to add 564 combatants to then existing forces, which had gradually built up to 693 men, some units were shifted and equipment re-assigned. The 8th Division also enters the campaign as the guerrilla forces have crossed to its jurisdiction, finally the area of operations is divided in three sectors and new responsibilities are given to troops on the ground.

At the air force level, the AT-6s and F-51Ds begin employing napalm on their bombing missions; K-17 aerial reconnaissance cameras as well as munitions are requested to the U.S. Finally, coordination with ground commanders is implemented in order to better guide air strikes. Company leaders operating in areas considered to be “hot” are provided with PRC-9 and PRC-10 radios which they use to relay communication to each other or to the liaison planes flying overhead, they in turn call in the combat squads flying on standby; the rudiments of CAS are finally implemented.

As far as combat situations, the first encounter of this phase occurs in the Cafetal area on June 10, when the Trinidad company (non-organic to any regiment) encounters a group of the enemy on a margin of the Río Grande; as a result one soldier is killed and another wounded. The company uses its mortars to attack the position and calls for support; one company from the Mendéz Arcos regiment is deployed to the area. The guerrilla diverts its route and starts marching towards the Rosita river in order to reach the town of La Florida, while the air force continues its patrol missions using both Mustangs and utility planes, which are unable to spot the guerrillas, but forces them to walk at night and slows their progress.

On the 25th the guerrillas reach the outskirts of La Florida and send some men to purchase goods. A mixed company from the 8th division (which includes a section from the Alianza Marine Infantry battalion) arrives that same night; on the 26th of June a patrol from the mixed company is ambushed and three soldiers are killed, one of Guevara’s men -Tuma- is also killed. The guerrillas now withdraw Northward towards the Cochabamba-Santa Cruz road, having been unable to recruit new combatants, gather supplies and now diminished to 24 men, the march is indeed painful. Soon after this combat, judged positive by the military command, the presence of Ernesto Guevara as leader of the guerrilla force is finally made official.

The 8th division now organizes its positions of the various towns on the sides of the CBBA-SCZ road; the area to cover reaches 250km, so the companies available are divided in small groups in order to cover the area. One of these groups (in this case 10 men from RI13 Ustariz) occupies the town of Samaipata. On the 6th of July, using its vanguard group, the guerrillas manage to surprise the officer in charge and capture him; they then try to subdue the soldiers. One of the men, soldier José Verazaín Llanos, valiantly attempts to free his fellow men and is killed in the act. The guerrillas capture the 5 rifles and 1 machine-gun available to the troops and withdraw after gathering some food and medicines.

Expecting a strong military response the guerrillas divert their march South, and despite their need for medicines they continue marching without occupying any other towns, hiding from the locals. Liaison and reconnaissance flights continue flying over the area; Pacho and Guevara duly note their impressions on the effectiveness of these missions12. The Trinidad company is sent to track the guerrillas on their march South, they lag behind them by a few days. On July 27th both forces reach the area of Corralones, one of the Bolivian groups spots the guerrilla from one side of the canyon to the next and mortars their positions. They also call for air support (AT-6s) that does not arrive from Camiri on time. Another group of the military is ambushed by the rearguard of the guerrillas; as a result one civilian guide is killed. On July 30th, on the area known as Morocos, the vanguard group of the Trinidad company accidentally collides with the enemy; a fierce combat follows through the night. As a result two of Guevara’s men are killed and others wounded, the casualties for the army are four soldiers KIA and four others wounded. Air support had been limited in this instance as no helicopters were available to rescue the casualties13.

The month of August is spent by the guerrillas marching South towards the Río Grande and their supply deposits (which have already been discovered by the army); demoralized and suffering from the lack of contact with the outside, lack of supplies and carrying their wounded; the guerrillas avoid contact with the military until August 26th when they fail to ambush a 7-men detachment patrolling the area. One soldier is wounded as a result, while the guerrilla hurriedly leaves the area.

Meanwhile, the guerrilla group left behind under the command of Joaquín, which following the orders from Guevara, had remained in the Southern part of the area of operations, marching on a seemingly haphazard manner for three months was finally detected by the military on early July. A group of the Oxa company tracks the group for the next two months. The military finally caught up to the guerrillas on August 31, at the place known as Vado de Yeso, where 8 of the remaining 9 guerrilla members are ambushed by elements from RI12 and GC-8 (44 men) and killed14, one soldier dies in combat.

3rd Phase of Operations

Vado de Yeso signals the last phase of the counter-insurgency operations, after an initial period of surprise and high casualties, the army has realigned and is now ready to eliminate the guerrillas.

Back in the central side of the area of operations, a brief combat on Yajo Pampa a few days later (September 3rd) yields one casualty for the army, the military identifies this as main group of the guerrilla force and starts tracking them. One more company is sent to the area, a few days later this group finds the body of Tania, who was killed on Vado de Yeso and dragged down river. A helicopter is requested to transport the corpse, on an unexpected surprise the President joins the company for the next 24 hours, and participates in their search. This action strengthens the morale of the army.

Meanwhile, the guerrillas spend the month escaping from the military and avoiding contact with the locals, as a result they suffer from hunger and internal strife. Unable to sustain this situation they enter the town of Alto Seco on the 24th, where they purchase supplies and round up the men for a propaganda session. To the North, the Manchego Ranger Regiment is finally deployed to the area of operations, reaching Vallegrande on the morning of the 26th of September. Ranger Company “B” is sent South to join a Company from the Braun GC-8 which had previously spotted and engaged the enemy vanguard as they left La Higuera, the guerrilla casualties include 3 dead and 2 defectors; the military didn’t sustain any casualties.

The Ranger Company reaches La Higuera on the evening of the 26th and together with the Braun Company pursue the guerrilla group for the next 10 days. 2 other companies join the operation; the air force also joins in, increasing the number of reconnaissance missions. By then, the guerrillas are surrounded by about 190 men from the 3 companies. On October 8th the military caught up with the guerrillas and prepares an ambush, followed by an encirclement maneuver on the El Churo canyon. In preparation for the attack they call in the support of one helicopters, the 4th Division command also sends in 2 AT-6s armed with napalm and machine-guns on a CAS mission. Capt. Prado calls off the AT-6s, as it is impossible to clearly target the enemy without endangering the Bolivian troops. The combat that ensued results in 4 Bolivians dead and 4 wounded, 6 guerrillas are killed and others wounded. Finally, 2 guerrillas -one of them is Guevara- are captured; they are executed on October 9th.

The insurgency continues after Guevara’s death, the 10-men group that escaped El Churo is now lead by Urbano; in their march North they reach El Naranjal and on October 12th, they are met by a group of the Ranger regiment and engaged in combat; the combat yields 1 civilian and 4 military deaths. Of the military casualties 1 is an unarmed medic killed while tending to a wounded soldier, who is also killed. On the 13th, now in the area of Cajones, the Rangers confront the enemy and kill four guerrillas, with no casualties of their own. The 6 guerrilla survivors now lead by Pombo, escape North avoiding any contact with the military or the population. They reach the town of Mataral on November 13th and attempt to purchase civilian clothing and supplies. The military is quickly informed of this and a patrol from the NCO school engages the enemy killing one. The survivors retake their escape route and are not seen again until February of 1968, when they are able to evade an airborne deployment and escape to Chile.

Mataral is considered the last combat of the campaign; following this event the persecution of the guerrilla survivors becomes a police affair. In the area of operations, the remaining troops begin their de-mobilization on November 21st, with the last unit – the Ranger regiment – was de-mobilized on December 30th. The air force conducts a slew of transport operations during this phase, since some of units had been brought from other areas of the country. The combat element of the air force is also able to return to their normal bases of operation, which include La Paz and Cochabamba.

The aftermath of the insurgency transcends the military aspect to the political. Controversy over Guevara’s execution and the trials of Debray and Bustos occupies the mind of the populace. The military returns to their bases and begins an internalization process, which shapes doctrine and training for years to come.

Footnotes

1 As an example, between 1961 and 1973 the Havana airport received no less than 145 hijacked planes. Gran Historia Universal Larousse, Vol. 17 pg. 2145 (Chile: 1992).

2 FSB, a right wing party, had experimented with guerrilla operations in 1964.

3 FSB had its main hold in Sucre and Santa Cruz, while the PCB had a strong presence in La Paz and some mining towns in the highlands (altiplano).

4 “Air Base” doesn’t in this instance stand for the mere physical location of a number of units; its modern-day equivalent would be the “Air Brigade”. Aerial Detachments, however, are a remainder from Chaco War time organization.

5 Including Northern Santa Cruz and the Apolo province in La Paz, years later a second “Guevarista” guerrilla attempt would rise in the second location.

6 All combat dates as well as information about sorties flown are drawn from the work of Prado and cross-referenced with the diaries of Pacho and Guevara. Combat locations are in bold lettering prior or after the combat date. Official FAB records were not available.

7 The local police detachment had been tracking the activities at the Casa de Calamina for some time, as they were suspicious that it was being used as a cocaine factory. They even visited the property on two occasions.

8 YPFB is the national oil company of Bolivia.

9 Pacho refers to the 5 planes effective in this mission as Mustangs, it’s not clear if these were in fact F-51s or AT-6s.

10 Cuban army captain Jesus Suárez (Rubio).

11 The “San Juan massacre” was perpetrated on the 24th of June; all mining centers –previously declared “territorio libre”, by the local communist leaders- were militarized.

12 On July 18th, Pacho notes spotting two “T-18” planes flying over their position. These could very well be T-28s, however there is no further evidence on this.

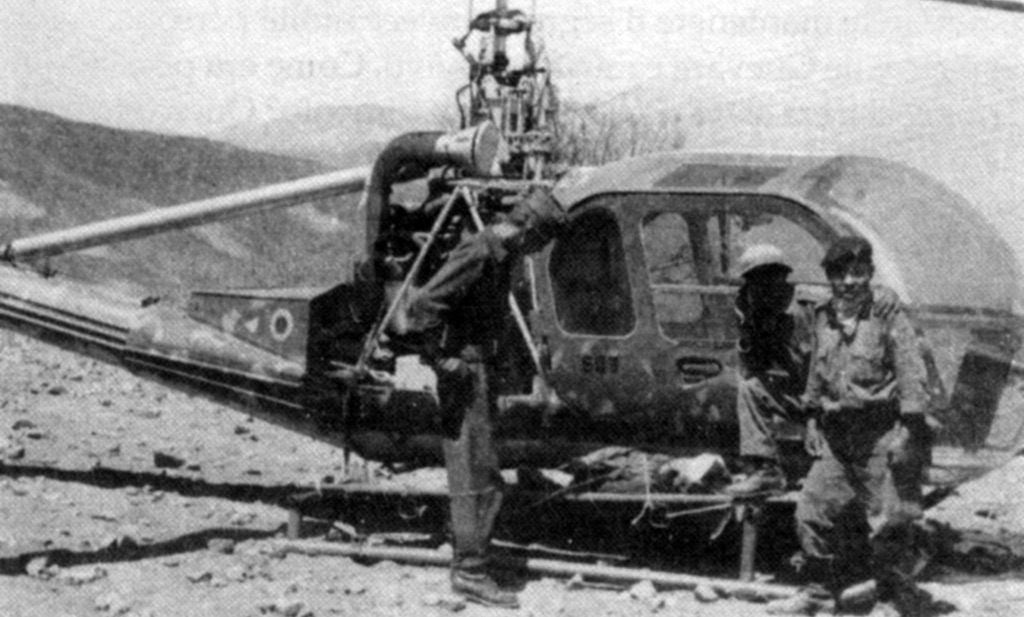

13 One of the H-23’s, commanded by Lieutenant Rolando Arévalo had crash-landed on the hills North of Postrervalle about a month earlier, its 2-man crew (the other crewman was Cap. Téc. Rolando Sandoval) remained stranded for 3 ½ weeks and was rescued on the verge of starvation. The helicopter was recovered and repaired, and served again in the campaign. The second H-23 was deployed in the Paraguayan border (Choroveca) at the time of this combat.

14 The Joaquín group originally accounted for 17 guerrillas, most are captured, surrendered or deserted; included in the last 9 fighters is Tania, the only female participant with the guerrillas, one Bolivian soldier is KIA on Vado del Yeso.

References

- Andrade, John M. Latin American Military Aviation, London: Midland Publishing, 1982.

- Dunkerley, James. Rebelión en las Venas 2nd Ed. La Paz: Plural Editores, 2003.

- Fernández, Alberto. Campaign Diary, included in CD attachment to La Guerrilla Inmolada 3rd Ed.

- Guevara, Ernesto. Campaign Diary, included in CD attachment to La Guerrilla Inmolada 3rd Ed.

- Hagedorn, Dan “Che Guevara in Bolivia”, downloaded text for Latin American Air Wars. Hikoki Publications, 2006

- Remírez Pilar, Ed. “La Revolución Castrista” Gran Historia Universal Larousse, Vol. 17. Santiago de Chile: Sociedad Comercial y Editorial Santiago Ltda., 1992.

- Prado, Gary. La Guerrilla Inmolada 3rd Ed., Cochabamba: Los Amigos del Libro, 2006.

- Prado, Gary. Poder y Fuerzas Armadas. Cochabamba: Los Amigos del Libro, 1982

- Prado, Gary & Hall, Lawrence Ed. The Defeat of Che Guevara. Westport: Praeger Publishers, 1990.

- Sandoval, Rolando. “Ñancahuazú una experiencia inolvidable”, Revista Aeronáutica No. 49. La Paz: Editorial Aeronáutica, 2003.

- Ustariz, Reginaldo. El Combate del Churo y el Asesinato del Che. Santa Cruz: Industrias Gráficas Sirena, 2005.

- Von del Hedyte, Friedrich. La Guerra Irregular Moderna. La Paz: Talleres Gráficos de Instituto Geográfico Militar, 1986.