The Birth of “Bomb Alley”

On the 21st of May, 1982, the British forces began disembarking on San Carlos bay, thus commencing the ground operations of the Malvinas / Falklands war. The Argentine high command, as soon as they received the first intelligence reports about the landings, made plans to bomb the British fleet. Despite the loss of twelve combat planes, the damage caused to the Royal Navy ships was considerable, especially if we consider that the Fuerza Aérea Argentina (Argentine Air Force) -FAA- and the Comando de Aviación Naval (Naval Aviation Command) -COAN- were flying very old aircraft. On that day, the legend of the Bomb Alley was born. These are some recollections from the Argentine side of the story…

The Day Begins

Three weeks had passed since the outbreak of the South Atlantic conflict and, after a few days of relative calmness, the long-anticipated landing of the British troops began materializing: Early in the morning on the 21st of May, 1982, the first Royal Navy vessels entered the Falkland Sound / San Carlos Strait. Shortly after, the bay was full of assault and landing ships, as well as frigates, with helicopters swarming overhead. A report from the Argentine observers, situated near the zone, was radioed to the headquarters in Puerto Argentino / Port Stanley, and two Aermacchi MB-339s of the COAN’s 1a. Escuadrilla Aeronaval de Ataque (1st Aeronaval Attack Squadron) were sent on an armed reconnaissance mission. Because one of them had problems with the landing gear, only the jet flown by Lt. (N) Owen Crippa, serial 4-A-115, took off at 9:00 AM.

Arriving in San Carlos at extremely low altitude, Lt. Crippa saw the British fleet and the helicopters coming and going from the ships and, without wasting any time, he went after the closest Westland Lynx helicopter he could find, firing his two 30mm DEFA cannons; In the last moment, however, he realized it was impossible to hit her at the angle he was coming from and decided instead to head towards the frigate HMS Argonaut, which he attacked with Zuni 5-inch rockets and cannon fire. As it would be expected, the crew of the British frigate returned fire with all they had. Luckily, by the time when the Argonaut’s extremely capable anti-aircraft system was activated, Lt. Crippa had already conducted his escape maneuver and was out of reach. Minutes later, Lt. Crippa made another pass over the strait, at much higher altitude, in order to count the British ships, jotting down their positions. This information proved to be invaluable for launching successive attacks on the fleet. In the end, Lt. Crippa departed the area and returned to his base in Puerto Argentino / Port Stanley.

The second attack on the British forces was conducted by the FMA IA-58A Pucarás of the Grupo 3 de Ataque (Attack Group 3) of the III Brigada Aérea (III Air Brigade.) Their mission was to launch strikes against the British land forces, especially a SAS group that was reporting the location of the Argentine forces so the artillery of the HMS Ardent could hit them. The first airplane that took off, FAA serial A-531, was flown by Captain Jorge Benitez. About this particular sortie Capt. Benitez stated:

“It was about half-past three in the morning when Operations told me about the mission for the first hours of the day: I would be conducting a reconnaissance over the Air Observers’ 5th position, since close to them there was a British commando airborne unit disembarking and had attempted to destroy their positions with machine gun fire. In the end, the men had managed to escape and continued radioing their reports.

The dark night finally ended with his mix of uncertainty, running, alarms and shootings that only left behind fatigue and tension. At 7:00 AM Lt. Néstor Brest and myself went to the Command Post to get an updated meteorological report and to get more information about the ongoing situation, and after that, we immediately went to the runway where the first light of the day found us getting ready for take off.

The alarm of an incoming bombardment went off right when we were in our cockpits, starting our engines. We immediately taxied to the runway, but only I was able to take off, since my wingman had to abort the take off roll as soon as the bombs began falling. In fact, he had to abandon the airplane and run for shelter.

During the first pass I didn’t see any British troops. I began a second pass, this time increasing the turning radius and at a higher altitude (50 meters) in order to cover more terrain. Shortly after, I noticed a British frigate at the San Carlos strait whose location hadn’t been reported yet. Thus, I cancelled the turn and initiated an approach to the ship from behind a hill. During the climb, I found myself in a much better position to observe the activity on the ship. Amazed by the turn of events, and regretting being armed only with cannons and machine guns, I continued getting close to the vessel, until something shook my airplane. At this point, I saw the smoke trail of a missile that had been fired at me, most probably by the British Special Forces. The projectile had been fired from the front and below, at about 150 meters, thus making it impossible for me to use my armament to return the fire. Not being able to determine the damage sustained by my airplane, I decided to dive into a small valley on my right and over the position where the enemy was, as to deny them any chance to fire another missile. About one minute later, I emerged from a valley located between the hills that are at the North and South of Port San Carlos, some 15 Km from where the missile had been fired at me.

As I began checking the status of my airplane, the right engine quit. Almost immediately, the flight controls stopped responding and the airplane began lifting its nose to 40 degrees up and going 30 degrees to the left. I spent the following five or six seconds trying to get the other engine’s propeller feathered, pushing desperately the right pedal and trying to trim the elevator down. With this, the nose went violently below the horizon, leaving me no other option but to punch out really close to the enemy position. Immediately, I felt the force of the initial ejection cartridges and the impact of the wind on my face. I saw the black hole of the cockpit I just abandoned disappearing below me; after the separation from the seat, I found myself floating down, safely hanging from my parachute.”

Capt. Benitez managed to avoid the British forces and during his walk to Darwin, he watched a pair of Pucarás, three IAI M5 Daggers, three Sea Harriers, two Argentine Chinooks and one Bell 212. In the end, he made it to Darwin around 19:00. Following Benitez’s morning take off, Major Carlos Tomba (A-511) and Lt. Juan Micheloud (A-533) managed to get in the air and headed to the location where the SAS group was operating. They found them hiding in a house that was promptly strafed. During this attack, one of the three Sea Harriers observed by Benitez shot down Maj. Tomba close to Drone Hill, but he was able to eject safely, albeit very close to the ground; on his part, Lt. Micheloud was able to escape and return to his base.

From the Mainland

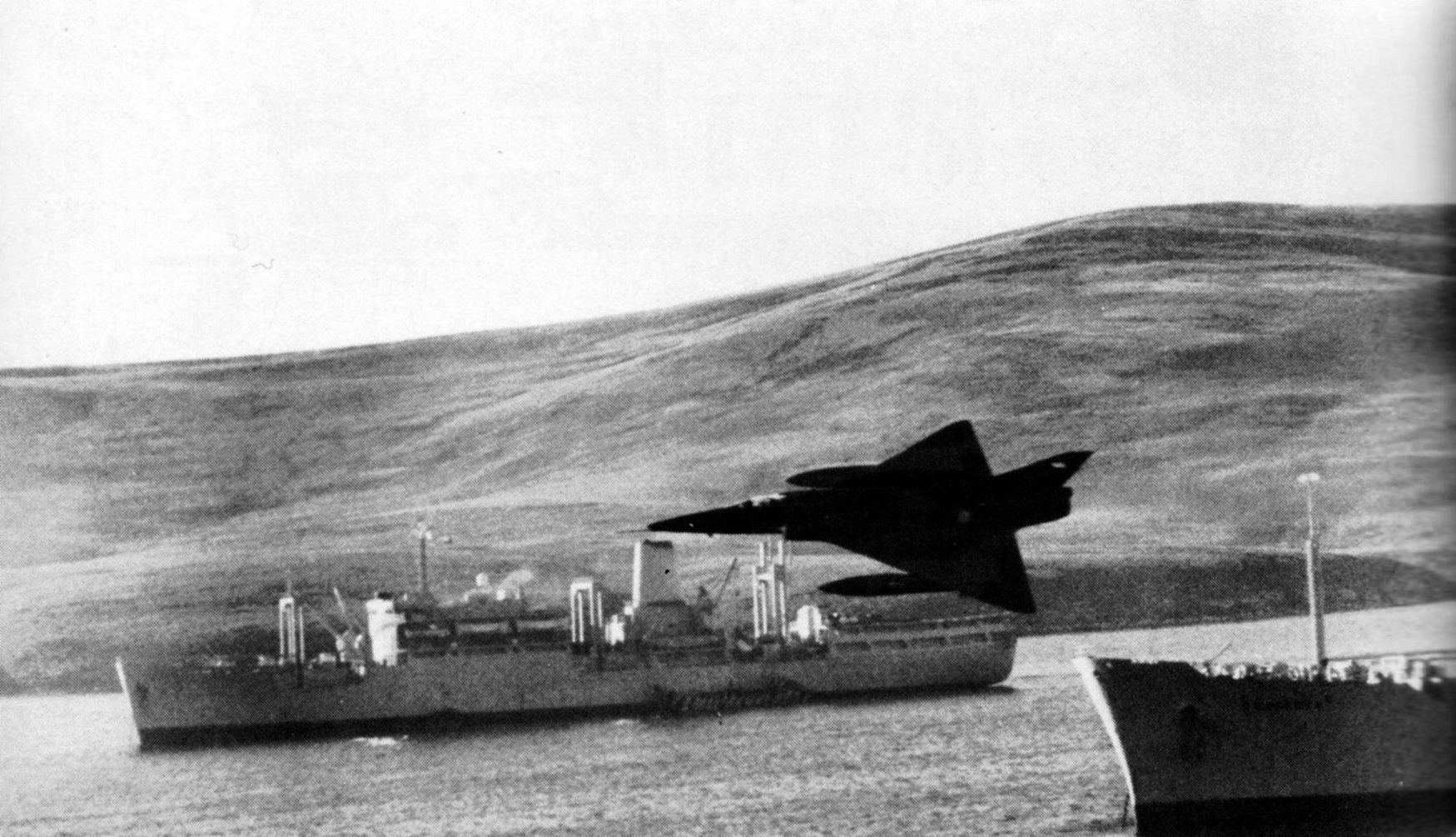

At 9:45 AM, the first flight comprised by three Daggers of Grupo 6 de Caza (Fighter Group 6) of the VI Brigada Aérea (VI Air Brigade) took off from the Río Grande airbase and set course to the islands. Using the indicative “Ñandú”, the pilots flying the mission were Captains Carlos Rodhe (C-409) and Roberto Janett (C-436), and Lt. Pedro Bean (C-428). They attacked the HMS Argonaut, the HMS Plymouth and damaged the HMS Broadsword. In the process, Lt. Bean was shot down by a Sea Wolf missile, fired precisely from the Broadsword. The Ñandú flight was followed by the “Perro” flight made of three Daggers (C-437, C-418 and C-435) and the “León” flight comprised of only two jets (C-404 and C-407), which had orders to attack the HMS Antrim. In both cases, the flights managed to inflict damage on the destroyer, but failed to sink her. The fourth flight, indicative “Zorro”, also comprised by three Daggers piloted by Captains Raúl Díaz (C-412) and Jorge Dellepiane (C-434) and Lt. Gustavo Aguirre Faget (C-415), was launched with the mission of sinking the HMS Brilliant. About this particular mission, Capt. Díaz recalls:

“As we approached the Gran Malvina (West Falkland), we began our descent with the intention of following a very low altitude heading to the San Carlos strait. As we began getting ready for the attack, I contacted the preceding flight and asked them about the situation in the channel. They informed us that there were several ships supporting the disembarking and that their strike had caught them by surprise. The British had assumed that the marginal meteorological conditions of the morning would prevail, diminishing the chance of any air strikes. In fact, they didn’t even bother to have any form of air cover.

When we arrived in the San Carlos bay, flying at only a few meters above the ground, the view before us exceeded our wildest expectations: The British ships were positioned in a semi-circle around the beaches were the disembarking was taking place. With no other option but to press on, we got in at maximum speed (about 550 knots) and headed for one of the nearest frigates. The approach was made a few meters above the water, with the jets flying one behind the other. Less than 1000 meters from the Type 22 frigate now centered in my gun sight, I opened fire with my cannons. According to the gun camera reel, the ship was hit several times just above the flotation line.

As soon as we were at the appropriate distance to drop our bombs, we discovered that the release mechanism wasn’t working, probably due to the freezing cold. The frigate didn’t respond to our attack either, maybe because we caught her completely by surprise. She only managed to escape from us by speeding away at maximum power. As we passed over her, it became apparent that the ship didn’t have Sea Wolf missile launchers, nor any artillery. Only a small helicopter was parked on her flight deck. It was another ship, located farther away and to our right, who began firing at us, albeit with poor results. On the other hand, it was quite surprising that despite our fuel drop tanks had hit parts of the ship’s structure as we passed over her, none of them had been punctured or sustained any considerable damage.

As soon as we passed over the frigate, we started evasive maneuvers in order to escape any missile fired from the ships. The situation turned ugly pretty soon, however, since the ships’ anti-aircraft artillery tried to create “fire-curtains” ahead of us. Instead of trying to hit our jets directly, they were attempting to shut us down by ‘circumstantial hits.’ It was a nightmarish scene to say the least: Water columns erupting from the sea surface, smoke trails from missiles criss-crossing before us and tracer bullets flying everywhere. In the end, we climbed the hell out of there and headed for the mainland where we arrived without any difficulties, just reflecting over the overwhelming military might we had witnessed.”

Through Tracers and Missiles

An hour after the departure of Zorro flight from the area of operations, it was the turn of the A-4Cs of the Grupo 4 de Caza (Fighter Group 4) of the IV Brigada Aérea (IV Air Brigade) based at San Julian. Organized in the “Pato”, “Tero” and “Rondó” flights, the Skyhawks serialed C-304, C-309, C-310 and C-325 approached the San Carlos bay and set out to pick their targets. As the jets began their descent, three Sea Harriers intercepted them, managing to shot down the jets C-309 and C-325, while the other two escaped after jettisoning the MK-17 bombs they were carrying. It seems that a Sea Harrier was lost also, since the Argentine pilots who escaped reported an ejection from one of the jump jets.

Shortly after, the Douglas A-4Bs serialed C-204, C-214 and C-231, of the Grupo 5 de Caza (Fighter Group 5) of the V Brigada Aérea (V Air Brigade) based at Río Gallegos, arrived in the area and didn’t wasted any time in picking up their targets. Using the indicative “Mula”, the Skyhawks bombed an unidentified British transport ship and, seconds later, a frigate that turned out to be the HMS Ardent. One of the 1000 lb. bombs hit the frigate’s deck and left her spilling black smoke. Here’s worth noting that the Mula flight was originally composed by four jets, but the one serialed C-250 had to abort the mission a few minutes after taking off.

The third wave of airstrikes was conducted by four A-4Bs also from the Fighter Group 5. The airplanes serialed C-207, C-212, C-221 and C-226, using the indicative “Pico”, arrived over San Carlos bay but failed to locate any exploitable targets. With nothing more to do, the four jets returned to Río Gallegos. After midday, the “Orión” and “Leo” combined flights, comprised by the A-4Bs serialed C-239, C-222, C-215, C-224 and C-240, all from the Fighter Group 5, arrived over the bay and promptly bombed HMS Argonaut before escaping safely. Minutes later, the Daggers serialed C-418 a C-436 of the “Cueca” and “Libra” combined flights, managed to hit the HMS Ardent a second time. A third Dagger, serialed C-409, flown by Lt. Héctor Luna, was intercepted by a Sea Harrier as it was descending towards the Ardent. Fortunately, Lt. Luna was able to eject and was rescued by an Argentine helicopter a few hours later.

The fourth and fifth waves of airstrikes arrived during the early hours of the afternoon. The first, using the indicative “Ratón”, was composed by the Daggers serialed C-403, C-404 and C-407, all from the Fighter Group 6. These jets were intercepted and shot down by a pair of Sea Harriers after a short but intense dogfight over the bay. The Argentine pilots, Maj. Gustavo Piuma, Capt. Guillermo Donadille and Lt. Jorge Senn were able to eject and were recovered later on. (There is an alternate and very controversial version for these shot downs, which states that the three Daggers were intercepted by no less than five Sea Harriers, and that one of the jump jets sustained damage after Capt. Donadille managed to hit her with cannon fire, forcing her pilot to eject.)

The next wave was comprised by the Daggers serialed C-421, C-415 and C-412, piloted by Lieutenants César Román and Mario Callejo, and Maj. Luis Puga respectively. Using the indicative “Laucha”, the flight had the responsibility of inflicting as much damage as possible on the British fleet. About this mission, Maj. Puga recalls:

“We crossed Gran Malvina at very low altitude and dove directly into the bay, searching for any frigates. One of them was spilling black smoke from her bow. A plume of smoke was also rising from her bridge, most probably as a result of a previous attack. Later on, we found out that it was the HMS Ardent. We kept going, really close to the surface, towards a Type 22 frigate ahead of us. When we were at approximately 2 kms from her, all hell broke loose as they opened fire at us with all they had. Among the images that I’ll never forget are those of tracer bullets coming at my jet. It seemed, however, that as long as we remained close to the water, they couldn’t hit us. The problem was that we had to climb at some point in order to drop our bombs.

As I was closing in to the frigate, now identified as the HMS Brilliant, I began pulling up, trying to keep her on my gun sight, but felt a strong impact that shook violently my jet. Thinking that I had been hit, I dropped the bombs and began escape maneuvers while checking my instrument panel for any signs of trouble. Incredibly, the venerable Dagger was responsive and kept flying fine. Minutes later, when we were overflying Darwin on our way to the mainland, I worried again because if my jet had any damage, it would be much better for me to eject over the islands than in the middle of the South Atlantic. Thus, I asked my wingman, Lt. Román, to fly under my airplane and see if there was any apparent damage. He did it and when he appeared on the other side, he signaled me that everything was OK. I checked once again my instrument panel for any alarms but everything was normal. In the end, I concentrated on taking our jets back to San Julian safely and forgot completely about it.

Back at San Julian, the mechanics who inspected my jet found that two of the three layers of bulletproof plexiglass of her windshield had been compromised by a direct impact. Had the third layer been compromised too, the projectile would have blown my head off! But that was not all: I felt a chill going down my spine when I remembered that the Dagger’s flight manual said that you could not exceed 200 knots with a cracked windshield. I had escaped from the San Carlos strait at more than 550 knots!”

Three days later, on May 24, a Sea Harrier shot down Maj. Puga off the coast of Borbón / Pebble Island, while flying the Dagger serialed C-410, as part of the “Oro” flight. Puga swam to shore and was rescued later on.

During the afternoon, the FAA launched four A-4B and five A-4C jets in what could be called an all-out effort against the British fleet. The Argentine pilots didn’t locate any exploitable targets, however, and had to return to their base in Río Gallegos.

The Navy Skyhawks in action

By mid-morning, the COAN set out to launch three flights of three Douglas A-4Q jets each from the Río Grande airbase, all assigned to the 3a. Escuadrilla Aeronaval de Caza y Ataque (3rd Fighter and Attack Aeronaval Squadron) or EA33 for short. These flights had been tasked with the mission of attacking the British fleet at the San Carlos strait in order to augment the air force efforts. The first one, led by the Captain Rodolfo Castro Fox, accompanied by Lieutenants Carlos Benítez and Daniel Olmedo, was ordered to return to base just as they were approaching the islands, since there was conflicting information about the position of the British ships. The second flight was comprised by Captain Alberto Phillippi (3-A-307) and Lieutenants José Arca (3-A-312) and Marcelo Márquez (3-A-314); they departed Río Grande around 14:10 and were followed by a the third flight fifteen minutes later, this one comprised by Lieutenants Benito Rotolo (3-A-306), Roberto Sylvester (3-A-301) and Carlos Lecour (3-A-305). The six jets were loaded with four 500 lb Mk-82 “Snakeye” bombs each.

The group led by Captain Phillippi had the responsibility of attacking the HMS Ardent, which they did successfully. In fact, the Ardent sank the next morning. However, the three jets were intercepted by two Sea Harriers as they were escaping the strait. About this mission Lt. Arca recalls:

“When I started the bomb run against the frigate, I only had seven or eight seconds of separation with the jet flying ahead of me, piloted by Capt. Philippi. The problem was that I needed to be no less than 20 seconds behind him in order to avoid the explosions of his bombs. I had ended up so close to his tail due to the heavy fire we were receiving from the nearby ships, which completely trashed my attempts to position my jet correctly for the attack. We were literally flying through bullets and explosions! I remember that I saw a missile being launched from the frigate we were attacking, which forced me to break violently to the right in order to avoid it. A second later, however, I corrected course and resumed the bomb run. Because of the extremely short separation with the jet of Capt. Philippi, I was able to watch in amazement how his bombs’ air brakes deployed. Until then, I was hoping his ordnance would miss the frigate, so the explosions wouldn’t obliterate my jet. A second later, I dropped mine and hoped for the best. Three of Philippi’s bombs missed the ship completely; the fourth one, however, was a direct hit on her stern. The explosion was immense and I didn’t have any other choice but to fly through the smoke and flames. As I began to climb out, I notified Philippi that only one of his Mk-82s had impacted the ship. Shortly after, I heard Lt. Márquez, who was flying behind me, saying ‘another on the stern.’

After escaping the area, I located Philippi’s jet flying one kilometer ahead of me and to the left, while Márquez was a bit further away, but to the right. As I tried to catch up with them, Márquez said that Sea Harriers were coming. Almost immediately, I saw one of the jump jets firing a Sidewinder which, after what seemed a really short flight, impacted the exhaust nozzle of Philippi’s jet. I looked to the right, trying to locate Márquez again but I didn’t see him. Instead, I saw another Sea Harrier closing in on me, firing her cannons. Shortly after, several 30mm rounds impacted my right wing. At that moment I was flying 3 meters above the water, and almost crashed when the bullets hit. Seeing that my jet was still responsive, I climbed immediately and went after the Sea Harrier that had fired at me, but the British pilot opened fire once again and almost shredded my left wing and damaged the hydraulics system. Flying at 480 knots, I turned to manual (unassisted) control, even though the NATOPS manual said that the top speed for doing this was 250 knots! With the jet more or less under control, I turned to face the Sea Harrier that still was after me. The ‘dogfight’ lasted less than 40 seconds, though, since the jump jet withdrew, possibly due to being short of fuel or ammunition.

With the jet more or less under control, I noticed that I had only 100 lbs of fuel, which was not enough to make it anywhere but Puerto Argentino. Hence, I decided to go there, following the coast at low altitude. Along the way I counted six bullet holes on my left wing and four on the right, as well as several fuel leaks. My next worry was to advise the airport at Puerto Argentino about my arrival, so the anti-aircraft batteries wouldn’t shoot me down, since the only jet fighters that flew over the airport were the Harriers. After a couple of tries, I managed to contact an Army helicopter operating close to Puerto Argentino, and his pilot alerted the airport.

While establishing a long final approach to Puerto Argentino’s airport, I lowered the landing gear only to discover that the indicator of the left wheel was red, meaning the it wasn’t down and locked. I notified the tower that I would be doing a missed approach, but needed someone to go out and seek what was wrong with my left landing gear. As I made a slow pass over the runway, the traffic controller said ‘you don’t have a left landing gear. I can see the sky through the holes you have in that wing; go and eject over the bay.’ Realizing that I didn’t have any other option but to punch out, I climbed to 2,500 ft and headed towards the bay where I pulled the ejection handle. After an explosion, I had the feeling of being rolling up through the air, and shortly after, I found myself floating down on the parachute. As for my jet, she continued flying and at some point turned back, as if she was refusing to leave me! She passed really close to me and, after some distance, began turning back again. It was then when the anti-aircraft batteries, aware of the danger, shot her down.

As I was floating down, I inflated the life vest, took my gloves off and, due to the proximity of the water, I decided not to release the liferaft. After splashing down, an Army Bell UH-1H helicopter came and tried to pick me up. The chopper wasn’t equipped with a hoist, though, so I began trying to climb up and get in only to fall back to the water every time. After almost half and hour of trying, I finally grabbed one of the skids with both hands and told them to take me to the beach, which was 500 meters away. Once there, the helicopter landed and I was able to get inside. Shortly after, I was on my way to the hospital at Puerto Argentino.”

Lt. Arca was flown to the mainland on an air force C-130H transport by the end of May. Regarding Lt. Rotolo’s flight, they arrived over the San Carlos strait through the Grantham sound, and bombed a frigate, which most probably was the HMS Ardent. Evading fire from other ships in their path, the three jets managed to escape towards the West at very low altitude, reaching Port Howard safely. Once over the West Falkland / Gran Malvina, the pilots climbed to 25,000 ft and headed back to Río Grande, where they arrived two hours later. To this day, it is not clear if any of the Mk-82 bombs dropped by these jets hit the British frigate.

https://www.laahs.com/wp-content/uploads/FAA-Attack-San-Carlos-Bay-1982.mp4

Epilogue

By sunset, twelve Argentine aircraft had been lost, and four pilots had been killed, three from the air force and one naval aviator. In total, the FAA launched 50 sorties and the COAN four that day, causing considerable damage to the British ships Arrow, Alacrity, Brilliant and Broadsword, putting out of commission for the remainder of the conflict the Antrim and Argonaut, and sinking the Ardent. Argentine air operations against the British fleet in the so-called “Bomb Alley” would continue until the 27th and, in the process, the Antelope and the Coventry would be sunk while the Sir Lancelot, Sir Bedivere, Sir Gallahad, Fearless and Avenger would suffer serious damage. The results are really impressive if one considers the age and obsolescence of the Argentine aircraft; it also speaks volumes of the skills, ingenuity and bravery of the Argentine pilots. They couldn’t stop the British, but they certainly impressed the world with their actions. As the French WWII ace, Pierre Clostermann, said on a letter to the Argentine pilots: “Never in the war history since 1944, pilots had to face a terrific conjunction of deadly obstacles, neither the RAF pilots over London in 1940 or the ones of the Luftwaffe in 1945.”